Schumann Bicentennial Celebration

On the Performance of Mozart's “Ave Verum Corpus”

by

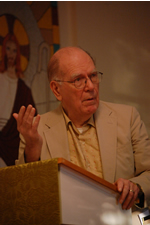

Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr.

Leesburg, Virginia

June 20, 2010

Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. |

Lyndon LaRouche made the following remarks at the celebration of Robert Schumann's 200th birthday, which was held at a local Leesburg church. His remarks followed the performance of Mozart's Ave Verum Corpus by the LaRouche Youth Movement Chorus. Afterward, the LYM Chorus again performed the motet.

This particular motet has long had a particular significance for me. It goes back decades in this matter, and I've always hoped to get it right. Because, what you're seeing here is something which is not in the score, but it's the intention which underlies the score itself, in this case, Mozart. Because it's not simply a repetition at the closing part of the chorus, here. It's a sense of true immortality.

Now, immortality is not simply something which is preached on at Sunday services.

Of late, we've had some progress in the scientific work, which assures me that I have a number of associates who understand clearly what I'm saying. And often, I've held back in life, when I've had a discovery of knowledge, I've held back in a public presentation of it, because, no one would really understand it. And I've found that among my Basement crew, in particular, that finally, we've reached the point, there is an understanding, of the nature of real human life, which lies not in the flesh as such, but lies in something which human beings can express.

We think of ourselves as being in the flesh. We think of ourselves as being seen, or heard, or smelled, for our presence. But that is not really what we are as human beings. Animals do that. Human beings are not animals. They're something else. We think in terms of sense-organs, and unfortunately, in society generally, people think only in terms of sense-organs as defining them, as defining them in the eyes of others, and defining them in the eyes of themselves, or the smell of themselves.

They don't realize that our senses do not show us reality. The senses show us the shadows cast by reality, the reality of the human mind. And all of our great principles, physical principles, for example, come from the practice of this understanding: That the truth lies not in the senses, or that which pertains to the senses as such. The senses give you the shadows of reality. Your job is to know how to interpret those shadows, to think of, and address specifically, the reality, which the shadows merely cast.

And thus, when we look at ourselves and our sense-experience, we should stand back from sense-experience, and look at sense-experience as an object to be looked at, because, for example, in any discovery, as in Kepler's discovery of gravitation, the discovery was based on using the contrast of two specific human senses, of sight and music, sight and hearing: It's the contrast between the two that enabled Kepler to make the discovery of gravitation. And that applies to everything.

We say then, we are, in a sense, see ourselves as actors upon a stage: But we want to see, say, actors who portray people from past history, as in a great Classical drama. So, we don't want to see them as standing onstage, now. We want to see the shadows of them, now, as cast by a hundred, or a thousand, or so, years ago. And we think then, if we, too, are onstage, as Shakespeare said once, "All the world's a stage," we want to see ourselves as we really are. We want to see ourselves, in a sense, as immortal, see us as we see a great performance of a drama. We see someone a thousand years past, or hundreds of years past: We see them. We see what they were, as we see the persons portrayed onstage.

And, in this music, in particular, that's exactly what's happening: It's a performance onstage, and these singers here, are singing--there's no question about that [laughter]. It's a question of sense-perception, you can hear them, you can't see them; if you turn the lights out, you can still hear them. [laughter] But, what they're representing, is, they're representing a situation, a historical situation, pertaining to the death of Christ. And through this medium, of this particular piece of genius by Wolfgang Mozart, you're able to capture a glimpse of that moment, and how the people who observed, and mourned, the passing of Jesus, how they--how we reach them. How you capture the moment in which they lived, captured that moment in which they lived.

And you have to learn, therefore, when you have a great composer like Mozart, who was a genius, much underestimated, actually--much-appreciated, but much-underestimated--to appreciate his insight, the power of insight, to convey with this particular motet. There are many versions of the motet, apart from Mozart before them. They're all rather trivial. They really don't convey the message. Mozart, in the artful way he composed this particular motet, when properly sung, conveys a sense of immortality. Because it captures a moment in real history, the moment at the time of the death of Christ. And therefore, when it's properly sung, under the proper circumstances, with the proper presciences in the audience, they actually live through--the audience, with the chorus, lives through, that moment in past actual moment of history. And it's a way of communicating a sense of the intrinsic immortality of the person, not in the flesh, but in the consequence of their lives for all mankind.

And this has a reciprocal feature, that it compels you, perhaps, if you're sensitive, to find your immortality, as you find immortality expressed on that occasion, after the death of Christ, over 2,000 years ago. You have a sense of immortality. And that's what happens in all great art, all great Classical art, and all great Classical music, in particular, is that thing that puts you at a distance from the present time, and gives you a relationship, an experienced relationship, which is more durable, which can take you back thousands of years, in terms of human art, that we know of, for example, from Homer and so forth, you get this sense of thousands of years of history, and you are there, and they here. And that is what this particular motet means for me. [applause]

Schumann Concert Program and Video

Related pages:

Schumann Concert Program and Video

Schumann Bicentennial Celebration Concert Text and Translations (PDF)

Greetings to the Celebration of Schumann's 200th Birthday in Virginia by Helga Zepp-LaRouche

200th Birthday Greeting to Robert Schumann by Harley Schlanger

Schumann Concert Program and Video

Schumann Bicentennial Celebration Concert Text and Translations (PDF)

The Musical Soul of Scientific Creativity: Rebecca Dirichlet’s Development of the Complex Domain (PDF 1.2 MB) by David Shavin

Robert and Clara Schumann, and their teacher Johann Sebastian Bach (PDF)

200 Year News Flash! Schumann Sighted at His Own Birthday Fest in Virginia! by Aaron Halevy (PDF)