A “Traditional” Tribute

For Two Solemnly Joyous Occasions

by Harley Schlanger

August 2008

The two following pieces were written to commemorate important milestones in two young couples' lives. The first, "Collaboration Redux," is a dialogue on the development of the ability to work together, which is necessary not only for a successful marriage, but in pursuit of any significant, shared mission. The second has a similar theme, while leaving a challenge to the reader to help solve what might be called an "ecumenical mystery."

The author has attempted to write in the manner of Sholem Aleichem, the great figure of the Yiddish Renaissance, whose eye for uncovering the not-so-hidden ironies confronting his beloved Jews of the eastern European “shtetls” and Russian Pale of settlement, combined with his insistent, but agapic chiding of those who stubbornly clung to their "old ways," enabled his readers to make discoveries, which eased their passage into modernity. Sholem Aleichem, I.L. Peretz and their collaborators in the Yiddish Renaissance, developed this "style" from their study of the great classics, including especially "Don Quixote" of Cervantes, and the works of Schiller and Heine. It is his hope that the contemporary reader will find this approach a useful one in outflanking the puffed-up egos one encounters in our society today. The two couples have graciously consented to allow the Schiller Institute to publish these pieces.

Introduction:

On Irony and Humor

by Paul Kreingold

What a pleasure it is for me to write an introduction to Harley Schlanger’s ironic celebratory dialogues. For a person raised in a home well-connected to the Yiddish Renaissance, the loss of irony in every day speech is extremely distressing. In my youth, the simple question, “How are you?” would often be answered, “So how should I be?” or “Don’t ask”. Every day language was chock-full of ironic flap-doodles, keeping the speaker and the listener’s mind alive and kicking.

I recently read a biography of Mussolini, in which the author quoted a contemporary of the dictator who said that what characterized his speeches was a complete lack of irony. Evil is not ironic, it may be sarcastic, cutting, sardonic and demeaning (which some people unfortunately find funny), but it is not ironic.

What is this secret of ironic humor with which Harley seeks to infect the world? Although humor is an important and necessary, weapon for those who wish to change the world, it is also a necessary ingredient of every day life because of what it does to the mind of the listener and the jokester.

Friedrich Schiller |

Frederich Schiller in his essay “Theater Considered as a Moral Institution” writes that one can lecture a man about his perversities and he will shake his head in agreement and walk away. But, make fun of his perversities and he will be touched to the quick, secretly glad that his perversities have been exposed. That comedy is, therefore, a greater power than drama alone in changing a man’s behavior and thought.

Schiller, therefore, considers humor as an agent to change men, and there are many examples of how this works, a recent example being Stephen Colbert’s monolog directed at Bush a few years ago. Although Bush didn’t change (well, Colbert is not God!), the event was the equivalent of an “Emperor Has No Clothes” moment for those viewing it.

One can also redefine the world for others with as little as a simple pun. I recall Lyndon LaRouche’s comment on former Auto Workers union leader Leonard Woodcock, “If the UAW were a potent union, they would not need a Woodcock!”

A well-told joke proceeds as follows. The jokester leads the listener into a small world. The listener, believing himself to be quite clever, sets up in his mind what he believes to be the axioms of that small world. Then, in an instant, the jokester releases the punch-line and POW! all the axioms crumble, the listener realizes that a whole other world exists, he jumps over to that other world, laughs, and his mind is free!

The German poet Heinrich Heine, in a letter to Moses Moser, on July 1, 1825 demonstrates his mastery of ironic humor.

Heinrich Heine |

“The joke in isolation is worth absolutely nothing. The only way I can put up with a joke, is if it has a serious basis. That is why the jokes of the Fool in King Lear are so strikingly powerful. The common joke is merely the sneezing of the [everyday] understanding, a hunting dog, who is pursuing his own shadow, an ape with a red jacket on, who finds himself between two mirrors, a bastard, begotten in the public streets, past whom run both Folly and Reason, -- No! I might say much more bitter things, if I did not recall, that the two of us have at times lapsed into telling a joke or two.''

Boy talk about irony! Heine, here, writes an attack on jokes which is really a joke about jokes! Harley’s dialogues are indeed in the tradition of Heine and Schiller, and will hopefully realize their intention to encourage others to escape from banality where evil lurks, for the lofty heights of ironic humor where one can, often, get a glimpse of truth.

![]()

Dialogue I

Collaboration Redux:

A Follow-up Inquiry, Premised on the Astounding Success of the Nearly-Complete Year VI

PROLOGUE: Nearly a year has passed since the now-celebrated dialogue, On Collaboration, was arranged, to offer perspective on the successful completion of five years of matrimony between Herr Michael and Madame My-Hoa Steger.

With the sixth year now almost completed, your humble narrator/moderator, Herschel Zvi, decided a follow-up was in order. This is not offered out of conceit, on Zvi's part -- though it must be acknowledged, that he was quite pleased, even puffed up, one might say, over the profound appreciation with which the original dialogue was received, as there was even some talk of a Lifetime Television network reality show -- but as part of a natural progression of inquiry, which is made necessary when taking up any subject which deals with a non-linear, anti-entropic dynamic operating in a self-bounded, but infinite context.

Unfortunately, Zvi was quite disappointed when he attempted to convene a session with last year's participants. Tony Soprano, who was retired last year by weary HBO executives, has no listed phone number. Efforts to locate him ended when two FBI agents dropped in on Zvi, and demanded to know why he was looking for Tony. They said they cannot reveal locations of anyone in the witness protection program, and he should just "fuhgeddaboutit."

Likewise, soon-to-be-ex-President Bush refused to respond directly. He left a message on Zvi's answering machine, in which he said, "I am no longer required to Co-la-bor-ate. I am too busy working on my Leg-a-sea to answer any questions. If you keep trying to reach me, I will send Karen Hughes or Mrs. Carville over to intimidate you, or Dick Cheney to shoot you."

Percy Shelley was sympathetic towards the venture, but unable to arrange the time. He sent an e-mail which explained that, given the world historic nature of the present crisis, in which the post-1971 era was coming to an abrupt end, he would be busy, testing his hypothesis that, at moments such as these, "there is an accumulation of the power of communicating and receiving intense and impassioned conceptions respecting man and nature," and therefore, he was preparing for that moment when poets would no longer be the "unacknowledged legislators of the world," but would, finally, be given their due. "This opportunity," he concluded, "is too precious to allow to pass me by."

Zvi replied that perhaps engaging in a serious dialogue about collaboration is one way to test his hypothesis -- especially since the Stegers relish the chance to test hypotheses. Zvi is still awaiting a response from the great poet.

As for Tevye the Dairyman, he was, of course, most gracious, though he, too, declined to participate. "I like those two," he said, "but you know how it is. The good Lord is a hard taskmaster -- you do some work, it's never enough, oy, I hate to kvetch, but there are so many mouths to feed. You know, my youngest granddaughters, Hodl's girls, are not yet married. One is so smart...alright, she's not much to look at, but the boys are afraid of her brains.

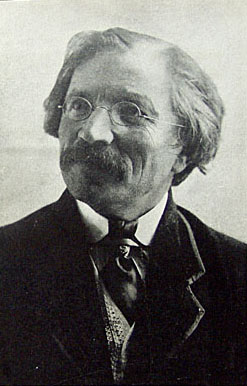

Sholem Aleichem |

"But, where was I? Oh yes, the Stegers. I wish them mazel tov, I'm kvelling over their growth. You, Zvi, you knew, and maybe Mr. Sholem Aleichem, that big wise guy, maybe he knew, maybe Rashi would have known, but most people here in Yehupetz, Anatevka and Glendale weren't so sure about them. You know the problem, when you have no money, all you have is troubles, which are free.

"Besides, tradition isn't what it used to be. In my day, you got married, and that was it, it was a life sentence, you did what you could. As I told Sholem Aleichem -- maybe you read this in his stories about me, I hear they used to be very popular -- `What's a wife for, if not to put a man in his place?' But in your day, there's a new tradition. A boy today thinks with his schemckle, maybe strays away, even forgets he's married, while the modern woman, she wants it all. I hear that in California, even the women sometimes act like they have a schmeckle....

"So, what do you want from me? Some advice? My beloved son-in-law, Motl the tailor, even he doesn't listen to me. He's a good boy, he works hard, but is poorer than the mice in my house. I told him, if you want to sew for a living, go to Guatemala!

"Please, give them my best, those two love-birds, but tell them, even for them, kine-ahora, I will not join another talk with that putz Bush. My Golde, she said he's the kind that gives the goyim a bad name. I must get back to work. Life isn't easy for a poor dairyman -- you think I make a shekle from the inflation in dairy products?"

With that, our dear Tevye slouched away, muttering to himself, something about King David, the Rothschilds, and the cholera epidemic in Odessa. What is Zvi to do, as the Stegers approach the all-important seventh year (as in the "seven year itch"!) if even his dear friend Tevye is too burdened to share some wisdom with the promising young couple?

In desperate straits, but still fiercely committed to the project, Zvi reluctantly decided he must convene a new panel, as the only other option would have been to interview himself. Of course, dear reader, you must recognize that this exercise would have been highly speculative, for, being a Boomer (though sometimes loathe to admit it), Zvi has had very little opportunity in his lifetime to actually collaborate. Only through his good fortune, to have married a woman who refused to allow him to NOT collaborate, does he have a clue or two, about collaboration, which might enable him to venture into this un-boomer-like terrain.

Thus, he dove headfirst into the unknown, to enlist a new team for this project. You may know that Zvi can, at times, be quite clever and resourceful, perhaps even persuasive, so it should come as no surprise that he was able to assemble a new panel. Since Rev. Jeremiah Wright, his first choice, is busy on a nationwide speaking tour, he settled for Sen. Barack Obama, even though it is clear that Barry, as he was once known, is often the beneficiary of others collaborating on his behalf, but possesses very little personal experience in how this process works. Rush Limbaugh, who never misses an opportunity to save people from the effects of the "drive-by media," was happy to be asked, even offering to host the discussion on the Excellence-In-Broadcasting network. (Zvi had to turn this offer down, as no one but Rush can be heard there.)

Two late additions filled out the panel. The first, Queen Elizabeth of Spain, entered the studio with a regal bearing, unbowed, despite the difficult relationship she has endured, over the centuries, with her husband, King Phillip II. Shortly after her arrival, the final participant rushed in.

"I bid you welcome," the Queen nearly sang, melodiously, in delight at seeing Franz Joseph Haydn race into the room.

Franz Joseph Haydn |

"I hope I'm not too late," he said, his breathing labored, as it appeared he had been running. "I had difficulty gaining permission from my employer, his Excellency Count Esterhazy, to attend this most historic gathering. I only wish my favorite collaborator, Wolfgang, could be here with us today." Zvi assured him there was no problem, then introduced him to the other panelists, so the proceedings could begin. And the rest, as they say, is history!

Key excerpts from their ensuing dialogue are transcribed below.

RUSH: Since I am here with talent on loan from God, and can conduct such deliberations with half my brain tied behind my back, I assume you want me to dominate, er, control, er, initiate this discussion?

ZVI: Mr. Limbaugh, you are here as a participant only, so, please, restrain yourself. I am here solely as a sherpa, to move things forward -- but, I am prepared to intervene, if necessary, to contain any egos.

RUSH: (whispers to Zvi -- I'm glad you clarified that, my friend, because, just between you and me, I think there are some really big egos in this room, if you know what I mean. By the way, my agent told me you would be providing oxycontin and Viagra for me. Where did you put it?)

ZVI: (ignores Limbaugh) - I think we would like to begin with some inspirational words from Senator Obama.

OBAMA: Thank you, thank you America. We all know why we're here. This is a time of HOPE, a time for CHANGE, a time when we HOPE for CHANGE, and CHANGE so we can HOPE. I love you, North Carolina....

RUSH: Uh, Sen. Obama, this is not a campaign speech. I believe you are reading from the notes prepared by your campaign staff over at MI-6 or Sky News. For this event, you should have notes from the social programmers from the Tavistock Institute, in that purple folder, the one that says "How to Pretend to Collaborate." Yes, that one.

OBAMA: Oh, sorry. Michelle and I both wish to apologize, from the bottom of our hearts, if what I just said offended anyone. As you know, we have decided to separate ourselves from the Trinity United Church -- not because of anything we did, but because of our concern that the intense focus on us may harm our friends and collaborators at the Church. You are all aware that one can collaborate with collaborators, without being collaborationists.

Take my long-term "collaboration" with Rev. Wright. We collaborated on good things, like Jesus and fighting poverty and AIDS, and bringing people together. All the bad things he says and believes, are not part of that collaboration. So, to summarize, we collaborate without collaborating, so that, uh, there can be CHANGE and HOPE, for we know that without HOPE....

RUSH: (under his breath) - I can't wait until Rove, Hannity and I get ahold of this guy...

OBAMA: I believe I detect cynicism, some of the old politics in your mumbling. Isn't it about time we get beyond the way things are done in Washington? No wonder there is no bi-partisanship.

RUSH: (mockingly) - That's rich, coming from you, with your liberal Democrat friends and your George Soros big bucks. You're just another left-wing elitist who never met a government program he didn't love....

ELIZABETH: Pardon me, perhaps I am in the wrong room. I was told there was to be a dialogue about the nature of collaboration, and how commitment to the betterment of others is a prerequisite for the kind of social dynamic which will result in profound and lasting transformation.

HAYDN: (Turning to Elizabeth -- I must say that I share your confusion. Thus far, I have seen only demonstrations of self-love. My invitation said that this was to be a session to provide some guidance for a young couple, who have taken upon themselves responsibility for the future -- from what I have heard of them, and what I have seen from this panel, perhaps they should be the ones offering their wisdom to the panel!)

ELIZABETH: (To Haydn -- I once thought one would find it lifeless only in Madrid. I fear our two co-panelists may convince me otherwise.)

HAYDN: (To Elizabeth -- I hope, for the sake of the Stegers, and our host, Zvi, that we may be able to collaborate, to evoke some humanity from Rush and Obama.)

ELIZABETH: (To Haydn -- We must endeavor to do so.)

(Addressing the whole panel) -- Gentlemen, shall we take up the task for which we have been summoned? I am prepared to speak of my sad tale, and how I learned that, though there may still be giants, there are no more knights; and that, therefore, my efforts at collaboration, though guided by the most noble thoughts and desires, were thwarted, and devolved to a most cruel, tragic end. But first, 'ere I speak, is there nothing which you two, Monsieur Rush and Senator Barack, can offer to the youth, who are so eager for your contributions?

RUSH: I, of course, can speak for hours of my great accomplishments, launched from the upper floors of the Limbaugh Institute for Advanced Conservative Studies. But, as you may have heard, my astounding success has little to do with collaboration. I work best alone, I am a rugged individualist. I believe that great things come from a man who, like me, stands on his own two feet, with no need of government. I am at the pinnacle of greatness, not because of a "collaborator," but because of who I am. That is why a nation of ditto-heads listens to me every day, religiously, so they can do what I tell them.

Ha! I think that's it! They collaborate with me, by doing what I tell them. That, my friends, is the essence of collaboration, even if the liberals don't like it.

OBAMA: Your arrogance is an affront to our democracy! You may have ditto-heads, but I have millions of contributors.

RUSH: Yeah, courtesy of George Soros.

OBAMA: Well, Soros is a firm believer in the Audacity of Dope! I have gained much from my collaboration with him, with Rezko, with Bloomberg [to himself, chortling -- like maybe the Democratic nomination].

I think that, had our poor Queen Elizabeth cultivated collaborators such as these, my "faith-based" friends, she could have won over Alba and saved Posa, though Carlos was too hot-blooded to be helped. You know, he reminds me of Rev. Wright. She should have renounced him, thrown him under the bus, the way I handled Wright, Father Fleger, and Farrakhan.

You know, I think Chris Mathews and Keith Olberman are right, I am really good, and charismatic. No wonder they love me! I get excited, just thinking about myself! Anyway, enough about me. What's your story, Haydn?

HAYDN: In my day, we called what Mr. Rush described, "subservience," and what the Senator has just uttered, we would call "self-serving." Neither of you seem to possess any insight into what is involved in "collaboration."

RUSH: Great, just what we need, a victim.

OBAMA: Let's hear him out. Victims usually find me quite appealing.

HAYDN: Were it not for your presence, my Queen, I would flee back to Count Esterhazy. At least he has no pretensions that he is a modern man.

With your leave, your royal highness, I wish to relate, briefly, the history of my collaboration with two great men, Mozart and Beethoven. To have known their music would have been enough for me to have died a happy man. But, to have worked with them, to have observed their agile minds in action, to have been in the presence of their genius, and to have played a humble part in helping them gain insights into the workings of their own minds, is almost too much for a mere mortal like myself.

ZVI: You are too modest, gentle sir. I have recently played some of your quartets. They are superb.

HAYDN: Oh, yes, well, I was a musician of some refinement. But it was only after I first encountered Mozart that I experienced what is true genius. It was at von Swieten's house, in 1781, when we rediscovered Bach. It was evident, at once, to all of us, that Bach had been a towering figure, for all time. What a mind was this! His music was heavenly! And though he had been long gone from this earthly domain, he was with us, collaborating with us, as though he were in the very room.

Young Wolfgang was beside himself with joy. I love these fugues, he enthused, they are so wicked. Take that, Fux, he exclaimed, roaring with laughter. Haydn, he said, join me at the keyboard, let us sing this one, and as his nimble fingers skipped over the keys, we joined in with a six-part chorus from the "Musical Offering." If I could have frozen that time, I would have, as I wished it would never end.

RUSH: Is there a point here? You know, I have to be on the air soon, and I have no idea where you're going with this. More people will tune in today to hear what I think than have ever listened to Mozart.

OBAMA: My time is also short. My staff is telling me that Hillary will soon end her campaign, and Rove is about to release an attack on my wife. Can you get to the point?

HAYDN: I am so sorry, gentlemen, to bother you with my reminiscences. I shall step aside, in deference to you and your temporal concerns.

ELIZABETH: Nonsense, you will continue, and I command you two to listen. While subordinating myself to my husband's court, I have unlearned this world's concerns, almost to where I have unlearned the memory of them. Herr Haydn's vivid memory of his collaboration is stirring me deeply. He is rekindling that most profound sense of responsibility for the condition of mankind that I imbibed at my father's court, and that was reawakened in my urgent dialogue with Marquis Posa.

(Sternly, to Rush and Obama) - You two could learn much from our musical colleague. Love should be your noble office, rather than raw, self-seeking ambition.

(To Haydn) - Please continue, good sir. I feel at home when you speak.

HAYDN: (casting a wary glance at the two self-important self-promoters, he then turns toward the Queen, and bows) - Your wish is my command, my lady.

Now, where was I? Oh, yes, at the Baron's. Mozart told me he had been inspired by the quartets I had composed in 1772. Called the "Sun" quartets, Mozart responded to them by composing his own. Then, nearly a decade later, as we were collaborating in Vienna, I was inspired by Bach, but even more, by Mozart's enthusiasm for Bach. I subsequently composed six quartets, which were called the "Russian" quartets, in honor of my patron. From the joint work with Mozart, I found myself free to compose, as never before. I inscribed the "Russian" quartets with the words, "written in a new and special way."

I discovered, several years later, that this had moved Mozart to new heights. In 1785, he dedicated six quartets to me, to his "beloved friend Haydn." I was so honored, so grateful. These quartets, oh my gracious, they were sublime. He paid homage not just to me, but to Bach. To play these quartets was a new experience, as though I was entering an empyreal realm where no human had ever set foot. Stunned by this experience, of playing these quartets for the first time, I told Mozart's father, who was with us in Vienna, that, "before God as an honest man...your son is the greatest composer known to me either in person or by reputation. He has taste and, what is more, the most profound knowledge of composition."

You should have seen Leopold Mozart's face. I believe your people, Zvi, use the word "kvell" to describe that look, one filled with such love, and hope -- real hope, Senator, which is not just a word which can be tossed about lightly -- he saw in his son the maturing of a creative artistic mind, of the sort which can lift mankind out of its infancy, a transformative genius for the ages. And I saw it too, developing in front of me. Oh, how I loved that man.

Not everyone shared my appreciation of him. There were some at the court who despised him, who saw his triumphs as their defeats. They tried to demean him, to scandalize him, to disrupt his performances.

They failed, as his genius rose above them and their pathetic efforts to hold back human progress. Most of those who attacked him are now forgotten, even by their progeny, while Mozart endures, as a towering immortal.

He was not just a quartetist, as some detractors alleged. He composed symphonies with new ideas, operas that moved the most hardened cynics, works for the voice, strings, even the clarinet, oboe and bassoon, and finally, an Ave Verum Corpus that invoked palpable images of the divine in man -- and then, without time for us to prepare, he was gone, taken from us.

I was devastated. Years later, if a friend would utter the name Mozart, I would burst into tears, telling my friend, "Forgive me, I must ever, ever weep when I hear the name Mozart."

(At that moment, Haydn lowered his head, and a tear was visible at the corner of his eye. Queen Elizabeth came over to comfort him; Obama checked his watch, while Rush shook his head in disbelief, and let a muffled profanity escape his lips. Haydn wiped his eye, cleared his throat, and continued.)

HAYDN: With Beethoven, it was different. He came to me to study counterpoint, and our relationship was more that of a teacher to a student. He was most gifted, but could be difficult. As I was older, and more consumed with my own creations, I was less patient. I suppose I was somewhat hurt, as I knew that he had hoped to study with Mozart, only to have to settle for me after Mozart's untimely passing.

Still, he worked hard, and one could see the uncompromising genius emerging. Looking back on my efforts with Mozart and Beethoven, I feel a small measure of pride to note that my great admiration for their potential has been affirmed by history. I saved a letter which I sent to the Elector in Bonn on Beethoven's behalf, which serves as a permanent record of my perspicacity. "Beethoven will eventually reach the position of one of Europe's greatest composers," I wrote, "and I will be proud to call myself his teacher."

We were never as close as I had been to Mozart. But I am proud to say that I collaborated with both of them.

[At this point, another squabble broke out between Rush and Obama. The heart-felt testimony of Haydn, which had riveted Elizabeth and Zvi, had made little impression on them. It had become painfully clear that there would be no collaboration, or useful thoughts on collaboration, coming from these contemporaries of the Stegers. As the hour was growing late, Zvi asked Elizabeth if she wished to offer any final thoughts on the subject.]

ELIZABETH: One always wishes, at a moment such as this, to be able to present a pearl or two, something tangible, which might offer some guidance for the future. Haydn has spoken with such eloquence of his experience. I cannot hope to match him, for my experience is that of a tragedy. That brilliant poet of freedom, Friedrich Schiller, has brought the tragedy of my life to the stage, so that others may gain insights from the horrors which were visited upon my people, due to the failures of myself, Carlos and Posa.

Some wish to absolve me of the blame, by pointing to the ignorance of my husband, who was caught in the powerful grip of the Inquisition, impotent in the thrall of that hatred. Others point to Posa, who they perceive to be a "tragic hero," one who acted with a noble intention, held himself to lofty ideals, and crafted a bold plan of action, which ultimately failed, however, because he was a "schwaermer," who took refuge in intrigue, believing he could use the Prince, poor Carlos, to attain his ends.

But can the good cause ever dignify the evil means? Did I do all I could to avoid the ultimate, inevitable collapse of Posa's plan? Could I have been more aggressive, more effective, in challenging my husband to obey Reason?

[At this point, Zvi noted nervous responses from Rush and Obama. Rush was vigorously patting his thinning hair, while Obama's leg was bouncing up-and-down. Was the noble discourse of Elizabeth reaching them?]

ELIZABETH: Alas, I must go. Mondecar and Eboli approach, they must get me home before my husband notices I have been gone. Do read Schiller's drama. It will change your thinking about collaboration....

[Exit Elizabeth]

[HAYDN arose, and gave one last, soulful glance in the direction of the two present-day would-be communicators]: I wish you well. You both possess an opportunity to reach people on a scale unknown to me, in my day. I hope you will use it wisely.

RUSH: Well, Obama, I leave you to ponder the deeper implications of this get-together. I have to run home and hide my porno collection before my soon-to-be fifth wife gets home. You would think that, after marrying four losers, I could find a woman worthy of my greatness.

[Zvi looked at Obama, who appeared to be shaken.]

ZVI: You must be tired, all this talk for the last sixteen months, of change and hope, and hope and change, tracking polls, fund-raising, all these meshuggener reverends. It's enough to make you crazy. A man must have some time to think, Barry, to challenge axioms, to develop new hypotheses. I have something for you. Before they left, the Stegers gave me this leaflet to give to you, something about kissing British ass and the so-called special relationship you claim you want with London. Come, let's have a bite, maybe some wine, a little chat. I think you can do better than cozying up to the Brits. Come with me. I want you to meet another friend of mine, Reb Tevye, oy, can he tell you about collaboration.

[As Zvi and Obama leave, strolling arm-in-arm, a Chorus can be heard in the background, reciting "Hope", by Schiller:

All people discuss it and dream on end

Of better days that are coming,

After a golden and prosperous end

They are seen chasing and running;

The world grows old and grows young in turn,

Yet doth man for betterment hope eterne.

'Tis hope delivers him into life,

Round the frolicsome boy doth it flutter,

The youth is lured by its magic rife,

It won't be interr'd with the elder;

Though he ends in the coffin his weary lope,

Yet upon that coffin he plants -- his hope.

It is no empty, fawning deceit,

Begot in the brain of a jester,

Proclaimed aloud in the heart is it:

WE ARE BORN FOR THAT WHICH IS BETTER!

And what the innermost voice conveys,

The hoping spirit ne'er that betrays.

THE END. (At least for another year!)

![]()

Dialogue II

A Wedding Day Bruchah (Blessing)

In Honor of the Wedding of Todd and Riana

Zvi was upset about something, but he couldn't quite put his finger on it. All morning long, he had been pacing, a bit out of sorts. Had he forgotten to pay the credit card bill? Had he left the oven on? What, oh what, could it be, that was bothering him?

If you know Zvi, you know that this is unusual. He is generally meticulous, well-prepared, a thoughtful sort who maintains his calm, no matter what might be going on around him. For example, he never complains about his near-pauper status. "It's only money," he would say. "You think money buys happiness? Look at that meshuggenah Donald Trump, he's richer than the Rothschilds, but he can't find good help, he's always firing people."

Though he cared deeply about problems in the world, his mischievous sense of humor often got him through the day. "That poor schmuck Bush," he was fond of saying: "Thank God he's not Jewish!"

If it was not money, or politics, what was it that was so pressing on his mind? Certainly not his marriage. For thirty-five years, his wife had been correcting him. Such a blessing! If not for her incessant reminders, he might forget to get dressed in the morning, or to turn off the faucet after washing the dishes at night. She only corrected him because she loved him! What more could a man want from a marriage?

No, he concluded, there is something else bothering me. I must go see my friend, Tevye the Dairyman. If anyone can help me figure out what's wrong, it's Tevye.

But Tevye was not in the barn when Zvi dropped by. Maybe he's doing his rounds, in Everett, selling milk and cheese to all the rich widows who waited for his visit every day. He asked Tevye's wife, Golde, when she expects him home.

Now Golde, there's a wife for you. She not only corrects him, she does it with gusto! When Tevye gambled away all the money they had saved, she said nothing. Well, it was almost nothing. He was exiled to the barn, with his horse and cows for the next two weeks, but, at least, she left him his dignity.

Tevye, she said, "he didn't go to work today. He went to town, he said it was important, he had to consult with the rabbi about something. His wife," she spit out, referring to herself, "she must know nothing, because he didn't ask her. That rabbi, all he does is read the Torah, the Talmud, twenty-three hours a day, what does he know, that Tevye's wife wouldn't know?"

In the awkward silence which followed, Zvi made up his mind -- he would join Tevye in the rabbi's office. It wasn't easy, however, getting away from Golde, who was full of suggestions as to what he and Tevye could do with themselves. Zvi bowed humbly, repeatedly, as he backed out the door, saying he would be certain to tell Tevye she wished to have a word -- or several thousand -- with him.

"Dear God," he murmured, as he left the porch. "You have showered our people with so many blessings, perhaps in my next life, there may be wives less committed to keeping us humble."

Upon arriving at the rabbi's study -- if you could call that small, cluttered, dusty room, with books stacked from floor to ceiling, a rickety desk, and a single, dim ray of sunlight coming through a tiny, filthy window, a study -- Zvi saw Tevye, huddled with the rabbi, over an old, faded book. Tevye shrugged his shoulders in greeting to Zvi, while the rabbi continued to peer intently at the page, stroking his beard, grunting as he read.

Zvi finally asked what they are doing. The rabbi looked up, barely acknowledging him, then bent back down over the book, his nose virtually pressing against the text. Tevye shrugged again, then motioned to Zvi to join him outside.

"Oy, Zvi," he groaned, "This is difficult. I received a communication about a wedding, from two distant acquaintances, they may even be related to my Golde. It seems they are to be married, but without a rabbi, without a huppa, and no glass to break. The wedding is soon, so I can't attend, but I wanted to know if I could still send a bruchah.

"I asked my Golde what I should do -- which is always my first thought, for, as you know, my Golde always has an answer -- and she gave me a piece of her mind, about modern kids, how they violate our traditions: they live together, they get married when they want, with no means of support, they don't ask our advice....On and on she went, it was like the plague that hit Kiev, there was no stopping it. What could I do? When she paused for a breath, I ran out the door, telling her I would see the rabbi."

Then it hit Zvi. He now knew what had been bothering him: of course, it's the wedding! He had been informed of the pending nuptials, through the grapevine, but he, too, would be miles away. He could afford no present, would he even be able to send his blessings in time? And, if so, what should he say?

"I know them also, Tevye, I heard about the wedding. I am reasonably certain they are not Jewish, though -- at least, I never met a Jew named St. Classis, nor one named Nordquist -- though perhaps they changed their names, you never know, maybe her name was originally St. Kaplan."

Tevye was puzzled. "Not Jewish? How could they NOT be Jewish? They're both so smart, she's so picky, he's so broke, they work so hard, they do nothing but study, they bring their families such tsouris. Are you sure they're not Jewish???"

At that moment, the rabbi shuffled out of the study. "Reb Tevye," he said hoarsely, "I believe I may have found an answer. But I must warn you, there are contradictory narratives to unravel."

He paused, waiting for a response. Tevye rolled his eyes. He was afraid of this. All this learning, study, parsing every sentence, every word, for years on end -- and all the rabbi could show for his learning, his studies and his parsing, was more contradictions?

Zvi jumped in, before Tevye blurted out one of his famous questions, such as "Why is it called the `Good' book, if nothing Good ever happens to the people who embrace it?"

"Rabbi," Zvi said, "Can you give us an answer? What should we do for this young, deserving couple?"

The rabbi hesitated, then cleared his throat. "Though there is no simple answer, we can narrow the options. You wish to know what kind of belated blessing you can send, when you weren't invited, they're most likely not Jewish, and they face a life of uncertainty, in a chaotic world? Have I summarized the problem?"

"Yes, go on," Zvi responded eagerly, hoping that a burden may soon be lifted from his shoulders.

"On the one hand," the rabbi began, prompting Tevye to interrupt, pleading, "Dear God, is it asking too much that you send us a one-handed rabbi?"

"As I was saying," the rabbi continued, "It is a problem if they are not Jewish. But, if they are not, we need not be concerned there is no rabbi, no huppah, no glass. And if they bring tsouris to their families, better that a family of goyim has the tsouris, than one of ours.

"On the other hand, I see that you both care about these two, that, despite the great distance, they are near to your hearts, and are in your thoughts. So, you can't communicate that to them? Isn't a belated greeting, a heart-felt communication, which expresses your love -- does that not count for something?"

Zvi and Tevye exchanged knowing glances. The rabbi might have found something; maybe all that learning, all that studying, and all that parsing really can make one wise. Zvi urged him to continue.

"Since God is all-seeing and all-knowing, I was convinced there must be something in our traditions to resolve your dilemma, a bruchah for virtuous goyim on their wedding day. But I asked myself, over and over, where could I find such a blessing? Our great prophets said nothing of note on this. I looked in vain in the writings of our learned scholars and teachers. You would think that, in all the years of exile, there would be more written of our relations with those outside our shtetls.

"At last, my hope diminishing, I tried one last source, a text in Greek, written by a confused Jew named Paul -- at least, I think he was Jewish, though some say he converted...but that's another story.

"Paul's words seem to resolve your dilemma, of what to say to this young couple, about their future together. I prepared a rough translation for you."

He handed a piece of paper to Tevye, with some verses scrawled in his distinct, barely-decipherable handwriting. "This is the best I can do. Now, I must go prepare for a visit from the widow Feldstein. I pray to God for the patience to deal with that woman."

As the rabbi left, Zvi asked Tevye to read the verses, which he did.

"When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

"For now we see through a glass darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

"And now abidith faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity."

Zvi was stunned. This is it? This is what the rabbi deemed an appropriate message to Toddalah and his bride? Then he noticed a wide grin spreading over Tevye's face, his eyes gleaming, a seemingly inner light flowing forth.

"I must hurry home to my Golde," he said, as he began walking away. "She will lecture me on how no one can understand what the rabbi is saying.""But Tevye," Zvi asked, "Will they understand?"

Tevye turned, and gave Zvi one of his world-weary shrugs. "They are young, they're smart, they study Plato and Kepler, and they do these things together. If anyone can figure out this mystery, they will."

As he watched Tevye disappear, Zvi was, at last, at peace. He would send the text via email to the newlyweds, and wish them a hearty Mazel Tov.

Then he would check to make sure he turned off the oven.

Related pages:

Drama as History: Clifford Odets’ The Big Knife and Trumanism by Harley Schlanger