Home | Search | About | Fidelio | Economy | Strategy | Justice | Conferences | Join

Highlights | Calendar | Music | Books | Concerts | Links | Education | Health

What's New | LaRouche | Spanish Pages | Poetry | Maps

Dialogue of Cultures

The Joy of Reading Don Quixote

by Carlos Wesley

|

||||

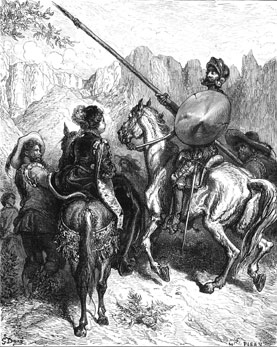

| Don Quixote, accompanied by Sancho Panza, agrees to slay a giant for Dorotea (Part I, Chapter 29). | ||||

This article is reprinted from the Fall 2003 issue of FIDELIO

Magazine.

For related articles, scroll down or click here.

In a survey conducted in 2002, some of the world's leading writers, representing nearly all continents, from Africa to Australia, Europe, Asia, and the Americas, selected Don Quixote as the world's best work of fiction. "If there is one novel you should read before you die, it is Don Quixote," said the Nigerian-born Ben Okri.1

This is a view shared wholeheartedly by our study group, which started reading Don Quixote aloud two years ago. We have just completed Part I of Miguel de Cervantes' (1547-1616) Seventeenth-century masterpiece, published in 1605, and are now embarked on Part II, which Cervantes published ten years later, in 1615.

For us, reading Don Quixote has been a most joyful undertaking, which some of you may want to consider doing, even if you don't read or speak Spanish; many of the standard English translations are more than adequate.2 By doing so, you would join the ranks of the many others, including America's founding fathers, who have read and enjoyed Don Quixote, over a span of nearly four centuries.

|

||||

|

Miguel de Cervantes

|

||||

After the Bible, Don Quixote is the most published literary work in the world. It has inspired countless movies and works of theatre, poetry, and music, starting as early as the English composer Henry Purcell in the Seventeenth century, and J.S. Bach's very-good friend, Georg Phillip Telemann (godfather of Bach's son, Carl Phillip Emmanuel), who composed the famous Don Quixote suite, and extending to Gaetano Donizetti, Felix Mendelssohn, and many others.

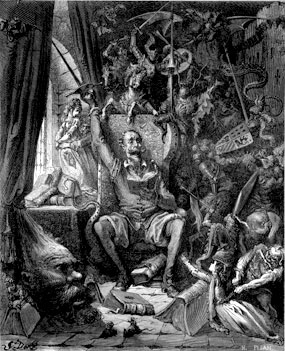

Holding Up a Mirror to Society

As most everyone knows, the basic plot of Don Quixote concerns the adventures a member of the lower landed gentry at the end of the Sixteenth century in Spain, who, having gone crazy from reading too many books of knight-errantry, decides to become a knight-errant himself, and, along with his neighbor, the peasant Sancho Panza, to whom he promises the "governorship of an isle" in exchange for serving as his squire, undertakes to travel across Spain. Along the way, they meet aristocrats, bureaucrats, and petty thieves, tradesmen, soldiers, priest and monks, dukes, duchesses, and whores, 669 individual characters in all, who are the real people of what Spain was at the time: the most powerful nation in the world, but fast on its way to inexorable ruin because of the stupidity of its people and the policies of the ruling Hapsburgs, particularly Phillip II (1527-1598), and his son, the indolent and venal Phillip III (1598-1621). While the former engaged in a cruel, but ineffectual, policy of repression towards the Low Countries, it was during the latter's reign that the expulsion of Spain's Muslim population took place, starting in 1609, completing the process of ethnic cleansing begun more than a century earlier, with the expulsion of the Jews during the reign of Phillip III's great-great grandmother, Queen Isabella (1451-1504).

Throughout the journey of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, besides holding up a mirror in which his contemporaries could see their strengths, and the follies that had brought them to this sad pass, Cervantes shows them (and us) how to get out of the mess, by, among other things, having the Don teach Sancho how to govern—lessons which the latter learns well, as we see later, when he rules the "isle of Barataria" in an exemplary manner. (That is, until confronted with a new situation that does not fit the axioms he has been operating under, when he is unable—or unwilling—to change, and quits the job.)

Many Layers of Meaning

While one can certainly get a lot of enjoyment from reading Don Quixote by oneself, there is a heightened sense of joy and understanding that comes from reading it aloud in a group setting, as we have learned in our study circle.

Our group came together in the year 2000, when this author assumed increased editorial responsibilities for the Spanish-language publications of the international movement led by Lyndon LaRouche, and realized there was a need to hone his own language skills, and those of a couple of his younger associates. Having learned from previous experience the salutary effects of reading Don Quixote, I proposed that the three of us get together occasionally to study some passages. To my surprise, at the appointed time for the first meeting, not only did the youngsters show up, but also several other colleagues, who wanted to join in the fun.

Our group at one time exceeded 20 persons—a somewhat unwieldy number—but eventually it settled to a much more manageable level of between 10 and 12 persons.

Although it has been over two years, and we are only halfway though the book, it has been so much fun, that no one has been in any particular hurry to finish. "Are you kidding? This is the highlight of my week! This is what I look forward to," commented a member of the group once. What better testimony to the power of the book, than the fact that it has held the attention of the diverse composition of our reading circle for so long?

Our group includes (or has included at different times) Hispanic migrant farm workers, with little formal education; native Spanish-speaking elementary-school pupils; high-school or college-educated native Spanish-speakers; and high-school or college-educated Americans, whose command of Spanish ranges from rudimentary to near-native ability. And, although not everyone (how could we?) gets exactly the same things from the book, every one of us enjoys coming together for one hour each week, each taking his turn to read a portion aloud, while the group's leader—sometimes this author, sometimes someone else—who has taken the time to research the chapter beforehand, provides the definition for terms that may be unfamiliar (not as many as one may think, as Cervantes' Spanish is remarkably modern), or explains literary, historic, or popular allusions, and such.

The one thing we try to avoid is "explaining" what Cervantes "meant to say," as we have learned that there are layers and layers of meaning hidden in the ambiguities of Don Quixote, that are uncovered as if peeling an onion, as LaRouche would say.

Take this example from Part I, Chapter 9:

This thought made me confused and eager to learn the true and authentic story of the life and marvels of our famous Spaniard, Don Quixote de La Mancha, light and mirror of Manchegan chivalry, and the first in our age and these calamitous times to assume the toil and exercise of knightly arms, to redress wrongs, to succor widows, to protect damsels such as those that go, with their whips and palfreys and with their virginity on their backs, from mount to mount and from vale to vale; and were it not that some ne'er-do-well, or some base fellow with his axe and steel cap, or some enormous giant forced himself upon them, there were damsels in the days of yore, that in eighty years of life, having not once in all of them slept under one roof, went to their graves with their virginity as intact as that of the mothers that bore them.4Some of these ambiguities—such as the Rabelaisian,5 "with their virginity on their backs, from mount to mount and from vale to vale"—virtually leap at any individual reading the book.

However, we have found that additional insight is gained from reading aloud, and from the discussion process that takes place in a group. This is no accident, because Cervantes designed the book to be read aloud—a necessity at the time, since it is estimated that as few as one percent of Spain's population could read and write, and the situation was not much better elsewhere in Europe.

So, throughout Part I of Don Quixote, Cervantes describes groups of shepherds in the fields, or travellers coming together at an inn, to hear someone read some book or other. And then, in Part II, Cervantes has people come together to discuss Part I of Don Quixote!

Two examples of things we understood better as a result of working together, come from Chapter 52, the last chapter of Part I, entitled "Of the quarrel that Don Quixote had with the goatherd, together with the rare adventure of the penitents, which with an expenditure of sweat he brought to a happy conclusion".6

The first, is Sancho Panza's reaction to seeing his master lying on the ground, after having been beaten by a group of religous penitents, whom Don Quixote had attacked, believing them to be kidnappers.

Fortune, however, arranged the matter better than than they expected, for all Sancho did was to fling himself on his master's body, raising over him the most doleful and laughable lamentation that ever was heard, for he believed he was dead. The curate was known to another curate who walked in the procession, and their recognition of one another set at rest the apprehensions of both parties; the first then told the other in two words who Don Quixote was, and he and the whole troop of penitents went to see if the poor gentleman was dead, and heard Sancho Panza saying with tears in his eyes, "Oh flower of chivalry, that with one blow of a stick has ended the course of thy well-spent life! Oh pride of thy race, honour and glory of all La Mancha, nay, of all the world, that for want of thee will be full of evil-doers, no longer in fear of punishment for their misdeeds! Oh thou, generous above all the Alexanders, since for only eight months of service thou has hast given me the best island the sea girds or surrounds! Humble with the proud, haughty with the humble, encounterer of dangers, endurer of outrages, enamoured without reason, imitator of the good, scourge of the wicked, enemy of the mean, in short, knight-errant, which is all that can be said!"Sancho's speech is funny, particularly the part where he describes Don Quixote as "humble with the proud, haughty with the humble," which seems at first glance to be an example of Sancho's well-known proclivity to mangle the language.

But, is it?

While this author could by no means be classed as an expert on Cervantes, I had previously read Don Quixote on my own several times. However, I—and others in the group who had read the book before—had missed the real joke in our prior readings, which only came out in the group's deliberative process: namely, that Sancho is not misspeaking; his description of the Don's behavior as "humble with the proud, haughty with the humble," is absolutely true!

This is shown earlier, in Chapter 33, "In which is related the novel of 'The Ill-advised Curiosity,' "7 the only instance in Part I where anyone calls on Don Quixote to exercise his calling to knight-errantry.

But while he was questioning him they heard a loud outcry at the gate of the inn, the cause of which was that two of the guests who had passed the night there, seeing everybody busy about finding out what it was the four men wanted, had conceived the idea of going off without paying what they owed; but the landlord, who minded his own affairs more than other people's, caught them going out of the gates and demanded his reckoning, abusing them for their dishonesty with such language that he drove them to reply with their fists, and so they began to lay on him in such a style that the poor man was forced to cry out, and call for help. The landlady and her daughter could see no one more free to give aid that Don Quixote, and to him the daughter said, "Sir knight, by the virtue God has given you, help my poor father, for two wicked men are beating him to a mummy."to get the permission. Having obtained it, Don Quixote,To which Don Quixote very deliberately and phlegmatically replied, "Fair damsel, at the present moment your request is inopportune, for I am debarred from involving myself in any adventure until I have brought to a happy conclusion one to which my word had pledged me; but that which I can do for you is what I will now mention: run and tell your father to stand his ground as well as he can in this battle, and on no account to allow himself to be vanquished, while I go and request permission of the Princess Micomicona to enable me to succour him in his distress, if she grants it, rest assured I will relieve him from it."

"Sinner that I am," exclaimed Maritornes who stood by; "before you have got your permission my master will be in the other world."

"Give me leave, Señora, to obtain the permission I speak of," returned Don Quixote; "and if I get it, it will matter very little if he is in the other world; for I will rescue him thence in spite of all the same world can do; or at any rate I will give him such a revenge over those who shall have sent him there, that you will be more than moderately satisfied"; and without saying anything more he went

bracing his buckler on his arm and drawing his sword, hastened to the inn-gate, where the two guest were still handling the landlord roughly; but as soon as he reached the spot he stopped short and stood still, though Maritornes and the landlady asked him why he hesitated to help their master and husband."I hesitate," said Don Quixote, "because it is not lawful for me to draw sword against persons of squirely condition; but call my squire Sancho to me; for this defense and vengeance are his affair and business."

Confronting Spanish Society

In the second example from Chapter 52 of Part I, Cervantes confronts the superstitions, false sense of honor, and other flaws of Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-century Spain, with the gentle irony that characterizes him, to even more devastating effect.

This is the fight with the penitents, which immediately precedes the scene with Sancho described above, as related in the translation by J. M. Cohen.8

The goatherd, who was now tired of pummeling and being pummeled, let him go at once; and Don Quixote stood up, turning his face in the direction of the sound, and suddenly saw a number of men dressed in white after the fashion of penitents, descending a little hill.Sancho attempts to hold him back:The fact was that in that year the clouds had denied the earth their moisture, and in all the villages of that district they were making processions, rogations, and penances, to pray God to vouchsafe His mercy and send them rain. And to this end the people of a village close by were coming in procession to a holy shrine which stood on a hill besides this valley. At the sight of the strange dress of these penitents Don Quixote failed to call to mind the many times he must have seen the like before, but imagined that this was material of adventure, and that it concerned him alone, as a knight-errant, to engage in it. And he was confirmed in this idea by mistaking an image they were carrying, swathed in mourning, for some noble lady whom these villainous and unmannerly scoundrels were forcibly abducting. Now, scarcely had this thought come into his head, than he ran very quickly up to Rocinante, who was grazing nearby and, taking off the bridle and shield which hung from the pommel, he had him bitted in a second. Then, calling to Sancho for his sword, he mounted and, bracing on his shield, cried in a loud voice to everyone present:

"Now, valiant company, you will see how important it is to have knights in the world, who profess the order of knight errantry. Now, I say, you will see, by the freeing of this good lady who is being borne off captive, what value should be set on knight-errantry."

"Where are you going, Don Quixote? What demons have you in your heart to incite you to assault our Catholic faith? Devil take me! Look, it's a procession of penitents, and that lady that they're carrying upon the bier is the most blessed image of the spotless Virgin. Look out, sir, what you're doing, for this time you've made a real mistake."Ignoring Sancho's protestations, Don Quixote approaches the procession:

"You who, perhaps because you are evil, keep your face covered, stop and listen to what I am going to say to you."Of course, they do not "give her the liberty she desires and deserves." Rather, they laugh at the Don, provoking his anger; he draws his sword and attacks, and they respond by giving him a beating.The first to stop were the men carrying the image, and one of the four priest who were chanting the litanies, observing Don Quixote's strange appearance, Rocinante's leanness, and other ludicrous details which he noted in our knight, answered him by saying:

"Worthy brother, if you wish to say anything to us, say it quickly, for these brethren of ours are lashing their flesh, and we cannot possibly stop to hear anything, unless it is so brief that you can say it in two words."

"I will say it in one," replied Don Quixote, "and it is this: Now, this very moment, you must set this beautiful lady free, for her mournful appearance and tears clearly show that you are carrying her off against her will, and that you have done her some notable wrong. I who was born to the world to redress such injuries, will not consent to your advancing one step further unless you give her the liberty she desires and deserves."

The whole scene is hilarious, and Don Quixote's confusing the penitents with kidnappers, brings to mind the famous incident where he confuses the windmills with giants. But, again, through the group's discussion process, another layer is uncovered. That is, that Don Quixote is correct in saying that those bearing the image, "who, perhaps because you are evil, keep your face covered," are "carrying her off against her will, and that you have done her some notable wrong," as "her mournful appearance and tears clearly show."

|

||

That this is, in fact, the case, becomes obvious when one correctly translates the term which most English versions render as "penitents," but which should be rendered as "flagellants." This is confirmed by the response Quixote gets from one of the priests, when he confronted the procession: "If you wish to say anything to us, say it quickly, for these brethren of ours are lashing their flesh." Thus, Don Quixote is not assaulting "our Catholic faith," as Sancho fears, but rather those—including the Inquisition-dominated Spanish Church—who are perverting it by engaging in sado-masochism in its name! That is, the Inquisition, which imposed dogma, thought control, instead of faith based on reason, has, indeed, "kidnapped Our Lady," and Don Quixote, whose madness frees him to see and say the truth, like the innocence of the child in the story "The Emperor's New Clothes," is pointing out the obvious. (This is made even more explicit in Part II, Chapter 9, where Cervantes has the Don say: "We have come up against the church, Sancho.")

In this, Cervantes was following the teachings of Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, who, along with his allies and co-thinkers—including François Rabelais, Thomas More, and the Spanish humanists Luis Vives, Pedro de Lerma, the brothers Juan and Alfonso Valdez, and the scientist Miguel Servet (whom John Calvin burned at the stake for heresy)—sought to do away with feudalism, reforming the Church and ridding it of superstition and hidebound dogmatism, and thus staving off the twin evils of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation which, launched and controlled by Venice, bled Europe throughout the Sixteenth century, and even more so during the Thirty Years' War of the Seventeenth, until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

Cervantes was an Erasmian. His first mentor was the Spanish clergyman and educator Juan López de Hoyos, the leading translator of Erasmus during this era. In 1567, Cervantes was a student at the school run by López de Hoyos in Madrid, and it was López de Hoyos who first arranged to have the works of Cervantes (whom he called "my dearest and beloved disciple") published, in 1569. It was also de Hoyos who arranged for Cervantes to obtain a position in Italy, where he spent the next five years.

Paradoxes and Ambiguities

One of the secrets of Cervantes' greatness is his masterful use of what LaRouche describes as proper human communication: that which "is based on ironies, on paradoxes, on metaphors, on ambiguities. So that what you say has a double or triple meaning. Good punning—not stupid word-play punning, but really good punning—is an ambiguity. And what you're doing, is, by posing an ambiguity; you're saying, 'What I say to you is this,' but you're disturbing the person you're addressing, because you're raising an ambiguity. And they say, 'What do you really mean?' And you do the same thing. So, what you do by posing a paradox, you force the mind of the other person to go through the process of solving the paradox. And thus, you communicate a meaning which is not located in a literal reading of the word, as a succession of object references, but a hidden meaning, which the mind of the person on the other end of the conversation is capable of recognizing."9 Thus, adds LaRouche, "the important part of communication is the ability to create paradoxes in the mode of your utterance which force the mind of the hearer to go search for the meaning of your utterance beyond the literal domain of known perceptual, sense-perceptual objects."

And this is exactly what Cervantes does throughout Don Quixote, as can be seen from the examples we have cited.

But, it goes beyond that: Cervantes not only poses paradoxes in nearly every individual scene of Don Quixote, but all of his major characters are themselves paradoxes. The Don is a deluded madman, believed to have been modeled by Cervantes on Phillip II, a monarch who started with good intentions, but who set Spain on the path to decay by his adherence to the attempts to reverse the Renaissance, and to the theocratic dogmas, imposed on the Church following the 1563 Council of Trent.10 But, in everything not having to do with knight-errantry, Don Quixote proves himself to be the wisest individual; for example, as is shown by the timeless advice he gives Sancho in Part II, Chapter 42.

"Rejoice, Sancho, in the humbleness of your lineage, and do not think it a disgrace to say you come from peasants; for seeing that you are not ashamed, no one will attempt to shame you. Consider it more meritorious to be virtuous and poor than noble and a sinner. Innumerable men there are, born of low stocks, who have mounted to the highest dignities, pontifical and imperial; and of this truth I could weary you with examples."11And, on how to be a good ruler:

"Let the poor man's tears find more compassion in you, but no more justice, than the pleading of the rich. Try to discover the truth behind the rich man's promises and gifts, as well as the poor man's sobbings and importunities."Where equity may justly temper the rigour of the law do not pile the whole force of it on the delinquent; for the rigorous judge has no higher reputation than the merciful. If you should by chance bend the rod of justice, do not let it be with the weight of a bribe, but with that of pity."

The Individual Person's Sovereign Mind

Cervantes' paradoxes are ontological in nature, in the sense of Riemann's "domain of physical" science, as LaRouche defines it in "Spaceless-Timeless Boundaries in Leibniz."12 LaRouche shows how Eratosthenes' experiment to test the "flat Earth" assumption—an assumption that the subject of the experiment lay within a two dimensional phase-space—produced evidence that showed a deviation from simply linear extension, requiring the introduction of a three-dimensional phase-space. As in the case of the Eratosthenes experiment, "We are able to show, and that in a fashion to which our pre-established beliefs could not object, that the disturbing fact has the same kind of experimental authority as we have supposed our pre-established hypothesis had had up to this time. However, the efficient existence of the new fact introduced, can not be accepted as valid theorem of the pre-established hypothesis. Thus, these two, equally validated sets of facts, can not co-exist in the virtual universe which we had believed we inhabited. A true paradox."

It cannot be denied, says LaRouche, that those two kinds of facts inhabit the same universe. "Confronted with such paradoxes, successful original discoverers have generated ideas which prove to be solutions. If we are able to validate these ideas experimentally, we call these ideas 'new physical principles.' The problem is, that although we are able to prove the existence of the discovered principle by experimental methods, we cannot represent explicitly, in mathematics, or in any other medium of communication, the mental process, entirely within the individual mind, by means of which such valid ideas are generated." What we can do, is "to repeat the discovery within our own sovereign cognitive process."

Cervantes does not "tell us" the solution, but, as does all Classical art, he provokes us to "repeat the discovery within our own sovereign cognitive process." While the outstanding, and indispensable feature of progress, says LaRouche, is scientific and technological progress, "the principles of Classical artistic culture have indispensable bearing upon the ability of a population to assimilate, and to generate the benefits of scientific and technological progress."

Think, for example, of the effect that Don Quixote, with its vocabulary of over 9,000 distinct words, had upon a Spanish peasantry whose average vocabulary has been estimated to have been as low as 500 (or even fewer) words! Not to mention the entire corpus of Cervantes' writings, with a total combined vocabulary of between 15,000 and 20,000 words.

In Praise of Folly

Besides uplifting the vocabulary of his countrymen, Cervantes sought to uplift their souls, to raise them to the level of self-governing citizens of a republic.

It is not known if Cervantes shared Erasmus' view that there were "hardly any Christians in Spain."13 But there is no question that, at that time, Spain was profoundly afflicted by a terrible disease of the soul, which the Spaniards called honor. A man of honor did not work; even intellectual work was considered dishonorable if done to make a living. And one had to keep up appearances: Travellers from other parts of Europe marvelled that almost everyone in Spain seem to claim some relationship with nobility. Artisans would show up for work dressed to the nines, work little, take long lunches, and quit as early as practicable. And, as soon as they made a little money, so said the observers, they would buy some title and give up working altogether.

In Part II, Chapter 44, Cervantes' alter ego, the Moor Cide Hamete Benengeli, in one of the rare places in the book where he speaks in his own voice, exclaims:

"Poor gentleman of good family! always cockering up his honour, dining miserably and in secret, and making a hypocrite of the toothpick with which he sallies out into the street after eating nothing to oblige him to use it! Poor fellow, I say, with his nervous honour, fancying they perceive a league off the patch on his shoe, the sweat-stains on his hat, the shabbiness of his cloak, and the hunger of his stomach!"14Even more important to honor was limpieza de sangre (purity of blood); that is, it was not what virtues a person possessed that determined his or her worth, but the purity of their bloodline, that they came from a family untainted by Jewish or Moorish blood.

Thus, in Don Quixote, Cervantes was taking on the historical-specific Spanish society—a society that was "upside-down," that had lost touch with reality, that rejected any new ideas, especially those ideas that it needed to reproduce itself—by counterposing the (apparent) madness of its protagonists, to what passed for sanity in that society. Cervantes forces the reader (as in the case of the cave of Montesinos, where Don Quixote lives through an experience that brings to mind the shadows of Plato's famous cave) to confront and resolve Pilate's infamous, "What is truth?"

In this sense, Don Quixote is as much in praise of folly, as Erasmus' famous treatise of that name.

And so are nearly all Cervantes' other works, whose subject is nearly always the madness of a society that believes in appearances while denying reality. Notably in the story "The Glass Scholar" and the interlude "The Pageant of Marvels," in which some townspeople allow themselves to be fooled by a couple of con artists into claiming they can see the biblical Salome dance, because if they admit the truth—that they cannot see her—they will expose themselves as having Jewish blood.

Thus we have Sancho saying in Part II, Chapter 22, "That may hold good of those born in the ditches, not of those who have the fat of old Christian four fingers deep on their souls, as I have."15 Note Sancho's proud use of the word fat in regards to his soul, an attack on the Spaniards of the Jewish and Muslim faiths, neither of whom ate pork.

Earlier, in Chapter 9 of Part II, the same Sancho says: "If I had no other merit save that I believe, as I always do, firmly and truly in God, and all the Roman Catholic Church holds and believes, and that I am a mortal enemy of the Jews, the historians ought to have mercy on me and treat me well in their writings."

Tilting at windmills because he believes that they are giants, as Quixote does, is certainly crazy behavior, as the Don himself acknowleges in Part II, Chapter 17:

"No doubt, señor Don Diego de Miranda, you set me down in your mind as a fool and a madman, and it would be no wonder if you did, for my deeds do not argue anything else. But for all that, I would have you take notice that I am neither so mad nor so foolish as I must have seemed to you. A gallant knight shows to advantage bringing his lance to bear adroitly upon a fierce bull under the eyes of his sovereign, in the midst of a spacious plaza; a knight shows to advantage arrayed in glittering armour, pacing the lists before the ladies in some joyous tournament, and all those knights show to advantage that entertain, divert, and, if we may say so, honour the courts of their princes by warlike exercises, or what resemble them; but to greater advantage than all these does a knight-errant show when he traverses deserts, solitudes, cross-roads, forests, and mountains, in quest of perilous adventures, bent on bringing them to a happy and successful issue, all to win a glorious and lasting renown."16

So, who is the true madman? The Don who tilts at windmills? Or the Spanish grandee who gains honor by fighting a bull in front of his king?

The Don, in fact, starts out as a representative of that idle nobility. At the very beginning of the book, he is presented as prefering to live in genteel poverty, rather than work his farmland and endanger his honor. He employs one farmhand and a housekeeper, and keeps himself in books by selling off plots of his land from time to time.

But as the novel proceeds, we see he and Sancho changing for the better, learning from each other, becoming nobler, in the true sense of the word, and in so doing, letting the readers know that we too can change, achieve our full potential, as Sancho does when he learns how to become a good governor.

Remember how in Part I, Chapter 33, Don Quixote refused to take up arms to fight against people of a lower station?

Compare that incident with what happens in Chapter 52 of Part II, when the Don is again asked to exercise his calling as a knight-errant, this time by the mother of a young girl who has been wronged by a cad. "I hereby declare that for this occasion I waive my gentry, lower myself to the meanness of the offender, and reduce myself to his level, thus granting him the right of combat with me; and so I defy and challenge him, though absent, by reason of the wrong he did in defrauding this poor girl, who was a maid and now by his fault is one no longer."17

The War of the Braying

One of the stories that best show how Don Quixote changes as the book advances, is the "war of the braying." Sancho and the Don come across a man walking with a mule loaded with lances and halberds. Eventually the man explains that the weapons are for a battle between two feuding villages. The feud started when an alderman from one of the villages lost an ass. A fellow alderman says he has seen the missing ass on the mountain, and the two set out to find it. After searching without results for a while, one of the aldermen says to the other:

"Look, my friend, I've just thought of a plan, by which we shall certainly discover the animal, even if he is hidden in the bowels of the earth, not to mention the mountain, and it's this: I can bray to perfection, and you can do a little in that line. Why, it's as good as done."This goes on back and forth for a while, with each alderman going around the mountain confusing the other's braying with that of the missing ass, until eventually they find the animal dead, long eaten by wolves. Even so, says the owner, "I am well rewarded for my labor in looking for him, even though I found him dead, by hearing you bray so gracefully, friend.""A little, you say, friend?" said the other. "Goodness me, I'll take odds of nobody, not even the asses themselves."

"Now we'll see," replied the second alderman, "for my plan is that you shall take one side of the mountain and I the other. We'll make a complete circle of it, and every few yards you'll bray and I'll bray. The ass can't fail to hear us and answer us if he is on the mountain."

"I think that's an excellent plan," replied the owner of the ass, "and worthy of your great mind."

Then they separated, as agreed and, as chance would have it, both brayed almost at the same time. Now each of them was taken by the other's bray, and ran to look, thinking that the ass had just turned up. But when they met, the owner of the lost beast said: "Is it possible, friend, that it wasn't my ass that brayed?"

"It was only I," answered the other.

"Then let me tell you, friend," said the owner of the beast, "that in the matter of braying there's is nothing to choose between you and an ass, for I've never seen or heard anything more natural in my life."18

Alas, the story soon gets out, and people from other villages, at the sight of anyone from the braying aldermen's villages, begin to mock them, "till now the natives of our braying village are as well known and as easily distinguished as Negros from whites." Eventually, they tire of it and decide to take up arms, "and in regular formation to do batle with the mockers."

On the appointed day of the battle, Quixote and Sancho come upon more than 200 men armed with spears, crossbows, pikes and other weapons, marching behind several banners. One stood out, made of white satin, with

a life-like painting of an ass of the little Sardinian breed, with its head up, its mouth open, and its tongue out, in the very act and posture of braying, and round it were writen in large letters these two lines:But, instead of joining the battle, as one would expect from his earlier behavior, Don Quixote seeks to be a peacemaker."They did not bray in vain,

"Our worthy bailiffs twain."

From this device Dox Quixote concluded that these must be the people of the braying village.

"Some days ago I learnt of your misfortune, and the reason which moves you to take up arms in order to avenge yourselves on your enemies; and having pondered your affairs in my mind not once but many times, I find that, according to the laws of duelling, you are mistaken in regarding yourselves as insulted, for no individual can insult a whole village, except by charging it collectively with treason, not knowing who in particular commited the treason which is the subject of the charge."Neither, he adds, can one man alone

insult a kingdom, a province, a city, a commonwealth, or a whole population, [thus] there is clearly no need to go out and take up the challenge for such an insult, for it is not one. ... No, no! God noes not permit or desire that. Prudent men and well-ordered states must take up arms, unsheathe their swords, and imperil their persons, their knives, and their goods for four causes only. Firstly, to defend the Catholic faith; secondly, in self defense, which is permitted by law natural and divine; thirdly, in defense of honour, family and estates; fourthly, in their kings service in a just cause; and if we wish to add a fifth count, which can be reckoned as part of the second, in defense of one's country."But,

"the taking of unjust vengeance—and no vengance can be just—goes directly against the sacred law we profess, by which we are commanded to do good to our enemies and to love those who hate us, a commandment which may seem rather difficult to obey, but which is only so for those who partake less of God than of the world, and more of the flesh than of the spirit."Again, paradox, irony, and ambiguity. The first four reasons cited by the Don parody the feudal code of honor. But "the sacred law we profess," which comands doing good to our enemies, is about a true, generative idea. In a sense, Don Quixote, the madman, is defined by his most crucial characteristic, his mind; being of the mind, and not of the material world, he is a truly spiritual being, which is why his actions are without guile, and guided (misguided) by love.

Agape

What Don Quixote has just described, is the principle of agape, the Greek term used by the Apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 13, which is sometimes translated as "charity," sometimes as selfless "love,"—love not for a specific person or object, but love such as that of Christ, willing to die for all mankind, or Joan of Arc, who gave her life, in a sublime act of sacrifice, in order to give life to France.

Throughout Don Quixote, Cervantes deploys agape against the ethnic and other prejudices of his countrymen, and by lovingly attacking the sins of his characters at the same time as he tells the sinners, "you are better than this," he shows that his characters—and, by implication, his readers—can be induced to change, can be organized to rise out of the muck. Cervantes demonstrates this throughout the book, beginning with when the Don, in his first foray, addresses the two prostitutes plying their trade at a roadside inn, as ladies worthy of being treated with dignity; or his insistence that the galley slaves—"men forced by the King, going to serve in the galleys," having being sentenced for a crime—be set free, "for it seems to me a hard case to make slaves of those whom God and nature made free."

And then, there is the relationship between the hidalgo Don Quixote, and his squire Sancho, where the Don seeks to uplift the illiterate peasant to the point he can govern, which he does accomplish; while, at the same time, Sancho teaches the self-proclaimed defender of the feudal order, that serfs are not cattle, but human beings; so that, in the process, they cease being master and servant and become equals, and friends. "What's more, we're all equal while we're asleep, great and small, poor and rich alike; and if your worship reflects, you'll see that it was only you who put this governing into my head, for I know no more of governing isles than a vulture; and if anyone thinks that the Devil will get me for being a governor, I had rather go to Heaven plain Sancho than to Hell a governor," says Sancho on the eve of assuming the governorship of Barataria.

" 'By God, Sancho,' said Don Quixote, 'if only for those last words of your, I consider you worthy to be governor of a thousand isles.' "

Perhaps it is this outpouring of agape, of selfless love, by Cervantes, which explains the popularity of the book after nearly four centuries. Nothing expresses this better that Cervantes' attitude towards the Muslims. If ever there were someone who could justifiably dislike, and even hate, the Moors, it was Cervantes. He had fought as a soldier against the Turks in several campaigns, including the famous naval battle of Lepanto, where he was wounded and lost the use of his left hand. Returning to Spain from military service, he and his brother were captured by pirates in the service of the Ottomans, and he was forced to serve for five long years as a slave in Algiers, before being ransomed.

Yet, he attributes the authorship of his book to the "Arabic historian, Cide Hamete Benegeli," and he claims to have hired a Spanish-speaking Moor from the Alcaná neighborhood of Toledo, to translate it from the Arabic, "and it wasn't difficult to find there an interpreter of such a language, for even were I to seek one for a better and older tongue [Hebrew-N-CW], I would have found him."

He has Benengeli open Part II, Chapter 8, with: "Blessed be the powerful Allah! Blessed be Allah!" And one can well imagine the effect this had in Spain at the time.

When discussing lineages with Sancho, Quixote says that there are four kinds: those who started humble and achieved greatness; those to the manor born, who kept their greatness; those who inherited greatness and declined, ending like the point of an upside-down pyramid; and the majority, who have had neither a good, nor reasonable, nor middling beginning, and will end the same, without renown, i.e., the lineage of the plebeian and ordinary people. To which he adds, "Of the first, who had a humble beginning, and achieved greatness which they now retain, the Ottoman house should serve you as an example, which starting from a humble and lowly shepherd is at the apex at which we presently see it."

But, it really gets interesting when it comes to the expulsion of Spain's Muslims, an event that was taking place at the time Cervantes was writting Part II of Don Quixote.

Sancho, now no longer governor, comes across some pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela. One of them reveals himself to him as Ricote, the Moorish former shopkeeper of Sancho's village.

"Don't you recognize me, Sancho?" Sancho looked at him carefully and began to recognize him, and finally he realized fully who he was, and without getting off his mount, he put his arms around him. "Who the devil would recognize you, Ricote, in that clown-suit you are wearing? Tell me: who has made you a Frenchy, and how do you dare return to Spain, where, if you are discovered and captured, it will go very badly for you?"19Ricote explains that he saw the expulsion order coming, and so he left to prepare a place for his family to settle:

"I left our village, as I said, and went to France, but though they gave us a kind reception there I was anxious to see all I could. I crossed into Italy, and reached Germany, and there it seemed to me we might live with more freedom, as the inhabitants do not pay any attention to trifling points; everyone lives as he likes, for in most parts they enjoy liberty of conscience. I took a house in a town near Augsburg." [Empahsis added]20His wife and daughter, although converts to Catholicism, end up exiled to North Africa. "Wherever we are, we cry for Spain, because, when all is said and done, we were born here and its our natural homeland." Ricote says he has now returned to collect some money he hid when he fled the country, with which he hopes to arrange to get his wife and daughter, Ana Felix, from Algeria, and take them back with him to Germany. He offers Sancho a cut to help him recover the hidden treasure, but Sancho turns him down, saying he is not greedy, and that he believes it would be treason to help the king's enemies, although, in any case, he will not turn in Ricote.

"And let me leave from here, Ricote my friend, that I want to get tonight to where my master Don Quixote."Later, after many twists and turns, Ricote and his daughter reunite in Barcelona, and gain the favor of the viceroy and another leading citizen, Don Antonio, in part thanks to their friendship with Sancho and Don Quixote."God go with you, Sancho my brother; my companions are stiring, and it is also time for us to continue on our way."

And they embraced each other ...21

Two days later the viceroy discussed with Don Antonio the steps they should take to enable Ana Felix and her father to stay in Spain, for it seemed to them there could be no objection to a daughter who was so good a Christian and a father to all appearance so well disposed remaining there. Don Antonio offered to arrange the matter at the capital, whither he was compelled to go on some other business, hinting that many a difficult affair was settled there with the help of favor and bribes.This is exquisite irony, indeed! To have the Moor Ricote voice popular opinion in defense of the policy of ethnic cleansing and the probity of Phillip III's administration, while two of Spain's leading citizens say outright that the court can be bribed, and that Spain's Muslims citizens and those of Muslim extraction do not present a threat to the country, and thus, by implication, that it is wrong to expel them."Nay," said Ricote, who was present during the conversation, "it will not do to rely upon favor or bribes, because with the great Don Bernardino de Velasco, Conde de Salazar, to whom his Majesty has entrusted our expulsion, neither entreaties nor promises, bribes nor appeals to compassion, are of any use; for though it is true he mingles mercy with justice, still, seeing that the whole body of our nation is tainted and corrupt, he applies to it the cautery that burns rather than the salve that soothes; and thus, by prudence, sagacity, care and the fear he inspires, he has borne on his mighty shoulders the weight of this great policy and carried it into effect, all our schemes and plots, importunities and wiles, being ineffectual to blind his Argus eyes, ever on the watch lest one of us should remain behind in concealment, and like a hidden root come in course of time to sprout and bear poisonous fruit in Spain, now cleansed, and relieved of the fear in which our vast numbers kept it. Heroic resolve of the great Phillip III, and unparalleled wisdom to have entrusted it to the said Don Bernardino de Velasco!" [Emphasis added]22

Inside and Outside the Novel

One of the ways Cervantes creates paradoxes that the reader must solve, is through his interpolated or "emboxed" stories, to borrow a term.23 These stories within the story, which are read or told by the characters in the novel—such as the tale of "The Ill-Advised Curiosity"—create another level, which makes the novel's characters "real" for the reader who is reading them over their shoulders, so to speak.

In Part II, Cervantes goes one better: he has the characters themselves comment upon their earlier actions which have now become part of world "history," so that from the point of view of the reader, the characters are apparently no longer fictional, but real, flesh and blood people.

Thus, in the second chapter of Part II, having returned from their first journey, Don Quixote asks: "Now tell me, Sancho, my friend, what do they say about me in the village? What opinion have the common people of me, and the gentry and the knights."24

To which the Don replies that "virtue is persecuted wherever it exists to an outstanding degree. Few or none of the famous heroes of the past escaped the slander of malice."

Sancho tempers the bad news, by giving Don Quixote an astounding report:

"The son of Bartholomew Carrasco, who has been studying in Salamanca, came home after having been made a bachelor, and when I went to welcome him, he told me that your worship's history is already abroad in books, with the title of The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha; and he says that they mention me in it by my own name of Sancho Panza, and the lady Dulcinea del Toboso too."Sancho adds that the book's author is one Cide Hamete Berengena, which means "eggplant" in Spanish, instead of his correct name, Benengeli.

"That is a Moorish name," said Don Quixote. "Maybe so," replied Sancho, "for I have heard it say that the Moors are mostly great lovers of eggplants." "You must have mistaken the surname of this Cide, which means Lord in Arabic, Sancho," observed Don Quixote. "Very likely," replied Sancho, "but if your worship wishes me to fetch the bachelor I will go get him in a twinkling."While Sancho goes to fetch the bachelor Samson Carrasco, Don Quixote ponders the fact that a book about his adventures has already been published, "though it made him uncomfortable to think that the author was a Moor, judging by the title of 'Cide'; and that no truth was to be looked for from Moors, as they are all impostors, cheats and schemers"—another paradox, for if that's the case, what he says about the Don in the book, will be a lie.

Soon, Samson Carrasco arrives with Sancho, and falls on his knees before Don Quixote, saying:

"Let me kiss your mightiness's hand, Señor Don Quixote de La Mancha, for, by the habit of St. Peter that I wear, though I have no more than the first four orders, your worship is one of the most famous knights-errant that have ever been, or will be, all the world over. A blessing on Cide Hamete Benengeli, who has written the history of your great deeds, and a double blessing on that connoisseur who took the trouble of having it translated out of Arabic into our Castilian vulgar town for the universal entertainment of the people."During the course of the ensuing dialogue, it becomes absolutely clear that Cervantes knew exactly the universal significance of what he was writing, that his masterpiece was not the result of happenstance, but that he was consciously creating a work for the ages (something he had already said explicitly in his dedication of Part II of Don Quixote to the Count of Lemos, where he jests that the Chinese emperor had sent an envoy to offer Cervantes the job of running a school in China, which would be created specially for him, to teach Spanish using Don Quixote as the textbook, but he had to turn down the offer, as the emperor did not send him the money to cover his traveling expenses.)

"So, then, it is true that there is a history of me, and that it was a Moor and a sage who wrote it?"Since this conversation is taking place in the story just one month after Don Quixote and Sancho have returned home from their first joint foray, it is simply astounding that more than twelve thousand copies were already in circulation, particularly at that time, when books were expensive and few people were literate."So true it is, señor," said Samson, "that my belief is that there are more than twelve thousand volumes of the said history in print this very day. Only ask Portugal, Barcelona, and Valencia where they have been printed, and moreover there is a report that it is being printed in Antwerp, and I am persuaded that there will not be a country or language in which there will not be a translation of it."

"One of the things," here observed Don Quixote, "that ought to give most pleasure to a virtuous and eminent man is to find himself in his lifetime in print and in type, familiar in people's mouth with a good name; I say with a good name, for if it be the opposite, then there is no death compared to it."Quixote then asks Samson "what deeds of mine are they that are made most in this history?" And the bachelor replies that"If it goes by good name and fame," said the bachelor, "your worship alone bears away the palm for all the knights-errant; for the Moor in his own language, and the Christian in his, have taken care to set before us your gallantry, your fortitude in adversity, your patience under misfortunes as well as wounds, the purity and continence of the platonic loves of your worship and my lady Dulcinea del Toboso."

"opinions differ, as tastes do; some swear by the adventure of the windmills that your worship took to be Briareuses and giants; others by that of the fulling mills; one cries up the description of the two armies that afterward took the appearance of two drops of sheep; another that of the dead body on its way to be buried at Segovia; a third says the liberation of the galley slaves is the best of all, and a fourth that nothing comes up to the affair with the Benedictine giants, and the battle with the valiant Biscayan."The book is so well written, comments Samson Carrasco,

"that children turn its pages, young people read it, grown men understand it, old folk praise it; in a word, it is thumbed and read, and got by heart by people of all sort, that the instant they see any lean hack, the say, 'There goes Rocinante.' And those that are most given to reading it are pages, for there is not a lord ante-chamber where there is not a Don Quixote to be found; one takes it up if another lays it down; this one pounces upon it, and that begs for it. In short, the said history is the most delightful and least injurious entertainment that has been hitherto seen, for there is not to be found in the whole of it even the semblance of an immodest word, or a thought that is other than Catholic."In the context of Spain at the time, this is completely subversive, for by claiming that there is not a thought in the book that is "other than Catholic," i.e., other than the established dogma, opens for the readers the possibility that such ideas do exist."To write in any other way," said Don Quixote, 'would not be to write truth, but falsehood, and historians who have recourse to falsehood ought to be burned, like those who coin false money."

Nonetheless, says Samson, some people have criticized the author for minor lapses in Part I, such as when in one scene Sancho's ass is stolen, and shortly after we see Sancho mounted on the same ass. "One of the faults they find with this history,' said the bachelor, 'is that its author inserted in it a novel called The Ill-Advised Curiosity; not that it is bad or ill-told, but that it is out of place and has nothing to do with the history of his worship Senñor Don Quixote."

"Then I say," says the Don, "the author of my history was no sage, but some ignorant chatterer, who, in an haphazard and heedless way, set about writing it, let it turn out as it might."

In the context of the age, this seemingly innocuous comment is truly a subversive idea: that the book was conceived in freedom by the "sage," Cervantes himself, according to a lawful principle, one that develops freely from the author's preconceived plan, and follows it's own internal truth, as life itself does, as opposed to the doctrinal straightjacket that constrained Spain at the time. As one author has noted, Cervantes deploys Plato and the "inquisitive 'St. Socrates,' " against "the rigid universe erected by 'St. Aristotle' and endorsed by the Council of Trent,"25 of dogmatic external structures imposed from above, in which everyone's place is fixed for all time by bloodlines, and people are told what to think and warned not to stray from doctrine.

Carrasco notes that the author of a book exposes himself to great risk, "for of all impossibilities, the greatest is to write one that will satisfy and please all readers." He also promises to take care "to impress upon the author of the history, that if he prints it again," he should include Sancho's corrections of the lapses in Part I.

"Does the author promise a second part at all?" said Don Quixote. "He does promise one," replied Samson: "but he says he has not found it, nor does he know who has got it; and we cannot say whether it will appear or not; and so, on that head, as some say that no second part has ever been good, and others that enough has already been written about Don Quixote, it is thought that there will be no second part." [This dialogue is taking place in the second part!-N-CW].If a second part is written, says Samson, it will be for the author to make some money. To which Sancho replies,

"The author looks for money and profit, does he? It will be a wonder if he succeeds, for it will be only hurry, hurry, hurry, with him, like the tailor on Easter Eve; and works done in a hurry are never finished as perfect as they ought to be. Let master Moor, or whatever he is, pay attention to what he is doing."26Let us pause for a moment, for by now you will have made the discovery that had our group bursting with excitement when we got to this point in the book, and you probably need to savor it, and reflect on it.

Let us go back over it together. We start with the Don asking Sancho the opinion of the people of the village, that is, of other characters in the novel. Then, Sancho brings the news that a book has been published about their adventures, something that is true in the real world, as opposed to the fictional world of the village. We now have the story developing on two planes: the fictional village, and the real world, where there is indeed a book called Don Quixote, which you, the reader, have in your hands. Samson Carrasco comes on the scene and confirms that the author is a Moor, Cide Hamete Benengeli, who has written it in Arabic, and that it has been translated into Castilian by a Spanish Christian, so now you, the reader, are dealing with three authors, and maybe more, for in Part II, Chapter 5, another "translator" is mentioned: Cervantes, whose name appears on the book in your hands, Benengeli, the Christian, and the translator.

Then you have Samson, Don Quixote, and Sancho, fictional (?) characters, who move between the village and the real world, where they conduct a dialogue with you, as actors on a stage make an aside to the audience, commenting on the book, daring even to criticize their creator, the author of the book.

The play, then—and it is a play—is unfolding on all these different levels, with all these different voices, within the stage that is in the mind of the reader, you, as if it were a polyphonic work by Bach, making you, by turns, one of the characters inside the book, at the same time as you stand outside, and above, the fictional action and characters.

As noted by William Byron in his biography of Cervantes: "The readers thus become characters in the novel, considering events happening outside its scope. The protagonists speculate on whether there will be a second part to their story and make recommendations to the author (which author?) as to how it should be told—a comment on a written record of event which have not yet happened by protagonists only partly informed of their own pasts. The sequence has been compared with Velázquez painting "as Meninas," in which the artist, the princess he is painting and the royal onlookers are so placed to put the viewer simultaneously inside and outside the room."

What we have then, is a truly philosophical novel, in the Platonic sense, where the folly of a society that believes in appearances, is confronted with the real world, and the readers are taught how to discover reality; a novel that opens the minds of its readers to truth, to agape—which is the same thing—by means of ambiguity, irony, paradox, and metaphor. Quixote is crazy, it is true, but because he is crippled by ideology—as the people of Spain were at that time—but, nontheless, he is conscious that his behavior is bizarre (or, at least, that it would seem so to the outside world).

It is noteworthy that Cervantes wrote Don Quixote when he was already an old man; in fact, most of his surviving writtings were published in the last decade of his life, starting with the first part of Don Quixote, in 1605, followed eight years later by the Exemplary Novels (1613); Voyage of Parnasus (1614); the Eight Commedies and Eight Interludes and Part II of Don Quixote (1615); and Persiles and Segismunda which he completed just before he died in 1616. After he returned to Spain from his Algerian captivity, he had embarked on a relatively succesful career as a novelist (La Galatea, which he sold to a publisher in 1584) and playwright ("I composed at that time between 20 and 30 comedies, all of which were staged without an offering of cucumbers or any other missiles; and fullfilled their runs without hisses, boos, nor uproars"). But, beginning in 1585, Cervantes published nothing for the next 20 years, during which he worked as a commisary for the Invincible Armada, was excommunicated, and was jailed two or three times for what one would today call "tax irregularities."

Why? The usual story is that the enormously popular Lope de Vega —whom Cervantes accused of being a familiar, i.e., an agent, of the Inquisition—was so succesful in imposing his style of playwrighting, that Cervantes found himself unable to compete, and thus was forced to retire. But, even assuming that Cervantes, who refused to follow what he considered Lope's anti-Classical style, could no longer find a theatre audience, there was no reason why he could not pursue his career as a novelist. After all, La Galatea was a pretty succesful book.

A more likely explanation is the political climate in Spain at the time. In fact, Cervantes' first notable public literary foray after this long hiatus came right after the death of Phillip II, in a satirical poem he wrote on the ocassion of the elaborate memorial services held in Seville for the dead king, which were scheduled for November 1598, but were interrupted after they began, called off, and held a month later, in December, because of a dispute between the Inquisition and the civil authorities regarding who had precedence in the seating arrangements! Cervantes took great pride in this poem, as he himself noted in the Voyage of Parnasus.

Don Quixote ends with the death of Don Quixote, who recovers his sanity just before he dies. "I was mad, now I am sane: I was Don Quixote de La Mancha, and am now, as I have said, Alonso Quijano the Good." He wills some money to Sancho, saying, among other things: "If while mad I played a part in obtaining for him the government of an island, now that I am sane, if I could give him a kingdom, I would."

And a kingdom, in fact, is what Cervantes has given us in his book Don Quixote—one which, it is hoped, having glimpsed in these pages, you will feel encouraged to visit right away, to open it, read it, and enjoy. And the best way, of course, would be aloud, with a group of friends, with whom to share the love and laughter, and the commitment to change.

|

Footnotes |

||

1.Reuters, May 7, 2002.

2.Among the good standard translations in circulation are those of Samuel Putnam, J.M. Cohen, and John Ormsby. There is also a more recent one by Edith Grossman.

3.Cervantes, by Melveena McKendrick (Toronto: Little Brown & Co. Ltd., 1980).

Thomas Shelton said he undertook to do the translation at the request of "a very deere friend that was desirous to understand the subject" of Don Quixote. He finished the translation in just 40 days, using an edition published in Brussels in 1607 by Roger Velpius. After his friend glanced at it, Shelton set aside the translation, and it sat "a long time neglected in a corner," until it was published in 1612 by William Shakespeare's publishers, Edward Blount and William Barret. This was Part I. In 1620 Blount published an English translation of Part II; although the translator is not named, the internal evidence indicates it too was done by Shelton, of whom a brief biography appears in the Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. XVIII.

John Fletcher, who with Shakespeare co-authored the play Cardenio based on a story from Don Quixote, succeeded him as an actor and leading writer of the King's Players. While Cardenio has disappeared, it was officially entered on the Stationers Register, an act akin to obtaining a copyright in modern times.

4.Author's translation.

5.Undoubtedly an Erasmian such as Cervantes read François Rabelais' (1494-1553) Gargantua and Pantagruel, probably in the original, as there is evidence that Cervantes knew French.

6. From the 1885 translation by John Ormsby. http://www.donquixote.com

7.Ibid.

8.Cervantes: Don Quixote, trans. by J.M. Cohen (London, New York: Penguin Books, 1950).

9.Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., "Classical Art: The Art of Communicating Ideas," The New Federalist, March 17, 2003 (Vol. XVII, No. 6).

10.Phillip II is famous for saying: "Before allowing any deviance in matters of religion or touching upon the service of God, I rather loose all my dominions and one hundred lives, because I don't want to be the king of heretics."

11.Ormsby, op. cit.

12.Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., "Spaceless-Timeless Boundaries in Leibniz, Fidelio, Fall 1997 (Vol. VI, No. 3).

13.Marcel Bataillon, "Cervantes et l'Espagne," in Revue de litterature comparée (Paris: 1937); cited in William Byron, Cervantes: A Biography (New York: Doubleday and Co., 1978).

14.Ormsby, op. cit.

15.Ibid.

16.Ibid.

17.Cohen, op. cit.

18.Ibid.

19.Author's translation.

20.Ormsby, op. cit.

21.Author's translation.

22.Ormsby, op. cit.

23.The term "emboxed" is used by Visnu Sarma to describe tales within tales, in her translation from the Sanskrit to English of the The Panchatantra (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1993).

24.Cohen, op. cit.

25.Byron, op. cit.

26.Cohen, op. cit.

27.Francisco Ugarte, Panorama de la Civilización Espa-ola (New York: Odyssey Press, 1963).

28.Byron, op. cit.

29.Ugarte, op.cit.

30.Quoted in Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Don Quijote de la Mancha, Prólogo y Esquema Biográfico por Américo Castro (México: Editorial Porrúa, 2000).

31.Steven Meyer (private communication).

32.Friedrich Schiller, Poet of Freedom, Vol. I, trans. and ed. by William F. Wertz, Jr. (New York: New Benjamin Franklin House, 1985).

33.Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, comprising portions of his dairy from 1795 to 1848, ed. by Charles Francis Adams (New York: AMS Press, 1970).

34.In Paul Zall, Franklin on Franklin (Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 2002). This book consists of the Autobiography, along with selections from Franklin's personal letters and private journals.

|

Boxes |

||

Spain under the Hapsburgs

Under King Phillip II (1527-1598), the relatively tolerant policies towards religious dissent of his father, the German emperor Charles V (1500-1558, who counted Erasmus among his official advisors), the first Hapsburg to rule Spain, were reversed, while Charles' disastrous economic and social policies were made even worse. Spain declared sovereign bankruptcy four times in the Sixteenth century, and most of the gold, silver and other wealth coming from its colonies in the Americas, went to pay debt to Genoese, Venetians, Dutch and other foreign bankers.

The privileges of the feudal Council of the Mesta, which had the right to drive its herds of sheep over cultivated fields, without paying any compensation to the peasants, who were prohibited from putting up fences, wrecked havoc with agriculture, a situation that was made worse after 1609, when Phillip III expelled the Spanish Muslims, called Moors, who were the country's most skilled farmers, leading to the collapse of the irrigation systems. Manual work—in fact, any productive activity—was considered anathema by the nobility, and by those that pretended to be noble, which was pretty much everyone else. Intellectual pursuits, commerce, science, were also considered a treath to honor, and there were few who engaged in these activities, especially after the expulsion of the Jews a century earlier, in 1492. The grandees, the upper aristocracy, were exempt from taxes, but so too were the lesser hidalgos, the clergy, and many others, so that the majority of taxes were payed by poor tenant farmers. It is estimated that in 1597, only 17 percent of the inhabitants of the city of Burgos were subject to taxation.27

The bubonic plague returned periodically, and some areas of Spain became virtually depopulated. In the Eighteenth century, the Bourbon king Charles III brought in German colonists to resettle the Sierra Morena, the scene of some of Don Quixote's most memorable adventures.

All government appointments required a "certificado de pureza," proving one was free of any taint of Jewish or Moorish blood.28 And then there were the thought police, the Inquisition. While the Inquisition was active at one time or another in nearly every European country, in Spain it took on a special character: it became a State institution, rather than just an arm of the Church, at times vying even with the monarch for power, and did not disappear completely until the Ninettenth century, although it had been weakened significantly earlier by Charles III. At the height of its power, specially after the Counter-Reformation launched by the Council of Trent (which was instigated and kept going by the Hapsburgs) officially imposed Aristotelian thought-control, the Inquisition "examined man's religious conscience without pity, even to its innermost spiritual sentiments. With religious fanaticism, and without Christian charity, it rigorously judged and punished any anormality or deviation from the fixed ideas held by the feared tribunal of the Inquisition."29 And, owing to the "inflexible intolerance of Phillip II and the Inquisition, Erasmian thought soon disappeared from Spain."

A Manual of International Statescraft

Cervantes' contemporaries were very aware of the world-historical significance of Don Quixote. Márquez Torres, who was assigned by the Vicar General of Madrid to censor Part II, wrote in his 1615 "Approbation," that Part I of Cervantes' masterpiece had had a tremendous impact "on Spain, France, Italy, Germany, and Flanders."30

He adds: "I certify as true, that on February 23 of this year, 1615, having my lord, the illustrious don Bernardo de Sandoval y Rojas, cardinal archbishop of Toledo, gone to repay the visit that he had received from the French Ambassador, who had come to deal with matters having to do with the marriage of their Princes and those of Spain, several French gentlemen of those who had come accompanying the Ambassador, as courteous and knowledgeable and friends of good writing as one could find, came to me and to other chaplains of the cardinal, my lord, wishing to know what books of inventiveness were most esteemed, and upon mention of this one, which I was censuring, as soon as they heard the name of Miguel de Cervantes, they started talking about the high esteem in which Cervantes' works, La Galatea, which some of them have almost memorized, the first part of this and the novels, were held in France, and in the surrounding kingdoms. Their praises were so numerous, that I offered to take them to meet the author of these works, for which they expressed their gratitude with a thousand expressions of ardent desire. They asked me in detail about his age, his profession, and his worth. I was forced to respond that he was old, of noble blood, and poor, to which one of them replied in the following terms: 'So, a man such as this is not sustained and made wealthy by Spain's public treasure?' Another one of the gentlemen replied with the following thought, and with much wit said: 'If necessity forces him to write, pray to God that he never has abundance, so that with his works, he being poor, he makes the whole world rich.' "

Cervantes well understood that he was fighting a rearguard action, similar to that of his English contemporary William Shakespeare, to save the achievements of the Fifteenth century Golden Renaissance, and to prevent the religious butchery of the Thirty Years' War, which loomed on the horizon. Thus, Don Quixote is, among other things, a political intervention. This is one reason it has been a favorite of statesmen ranging from the Philippines' José Rizal, to Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of independent India and father of Indira Gandhi, to Israel's first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, who "laboriously learned Spanish" so he could read Don Quixote in the original. Ben Gurion tried to reread it once a year, because he considered that all the secrets of statecraft were contained therein.31

Cervantes and Shakespeare

The Englishman William Shakespeare, who was baptized on April 26, 1564, was a contemporary of the Spaniard Miguel de Cervantes. In fact, they both died on the same date, April 23, 1616, though not on the same day, since England still followed the Julian calendar, whereas Spain had adopted the Gregorian one.

That Shakespeare knew Cervantes' work is clear, since he co-authored with John Fletcher a play, Cardenio, based upon the tale of Cardenio from Don Quixote, which was acted at court for the royal wedding of Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James I, to the Elector of Palatine, on June 8, 1613. The first English translations of Don Quixote, both Parts I and II, were printed by Shakespeare's publishers.3 It is quite possible that Cervantes knew Shakespeare's work as well, Cervantes started and ended his literary career as a playwright (Eight commedies and Eight Interludes). Both he and his fellow playwright, Shakespeare, sought, through their writings, to uplift their respective populations.

Both were "political" writers, as all real artists are. This is most notable in Shakespeare's history plays, but also in his works of "legendary" history, such as Hamlet and Macbeth, where the issue is how a society can deal with its flaws before they lead to tragedy.

Similarly in Cervantes, all of whose works take aim at the tragic flaw in Spanish society: the fantasy state of the "glory" of the medieval feudal past, versus the reality of a decaying empire. Compare Hamlet's crazy behavior, with that of the characters in Don Quixote. ("Who is more crazy: he who is thus because he can't help it, or he who is willfuly thus?", asks the peasant Tomé Cecial to Samson Carrasco, after the latter, posing as the "Knight of the Mirrors," has been defeated in battle by Don Quixote. "The difference between those two kinds of madmen, is that the one that is crazy by compulsion will always be thus, while he who is willingly crazy can give it up when he wishes.") What the artist seeks is for those who are willfuly crazy to get to the point were they wish to give up their disease.

But while Shakespeare worked in England, a society in which a nation-state had been established by Henry VII, Cervantes wrote in an environment that was not yet a nation-state (Castille, Aragon, Portugal, etc., all had their own laws, customs, and systems of taxation, although they were ruled by the same monarch). Spanish society had turned its back on the Renaissance, on progress, and become a racist police-state, rigid in its feudalist outlook.

Don Quixote and America's Founding Fathers

Perhaps no group of statesment enjoyed Don Quixote more than the Founding Fathers of the United States. "Dear sir: I have received your letters of the 29th of October and the 9th of Novr. The latter was handed to me by Colo. H[enry] Lee, with 4 Vols. of Don Quixote which you did me the honor to send to me. I consider them as a mark of your esteem which is highly pleasing to me, and which merits my warmest acknowledgment. I must therefore beg, my dear sir, that you will accept of my best thanks for them." So wrote George Washington in a letter, which he addressed from Mount Vernon on Nov. 28, 1787, to Diego Gardoqui, Spain's first ambassador to the United States. During the American Revolution, Gardoqui had functioned as the conduit for the millions of pounds that the Spanish gave to the American cause. Spain's financial contribution to the American Revolution was equal to that of France, with Gardoqui serving as the Spanish counterpart to the Frenchman Caron de Beumarchais, author of the play on which Mozart's opera The Marriage of Figaro is based.

Washington was not able to read the four-volume Spanish set of Don Quixote he got from Gardoqui, which can still be seen in his library at Mount Vernon, but he did read an English translation that he obtained soon after. Don Quixote was also a favorite of Alexander Hamilton, John Adams (who travelled with the book in his saddlebags), and Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson, as he told his son-in-law to be, Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr., thought that next to French, Spanish was the modern language "most important to an American," given that "our connection with Spain is already important and will become daily more so. Besides this the ancient part of American history is written mostly in Spanish." Jefferson supposedly taught himself Spanish in a few days in 1784, while crossings the Atlantic on his way to Europe, by means of a copy of Don Quixote and a borrowed Spanish grammar, according to what he later told John Quincy Adams in 1804. Adams took the story with a grain of salt: "But Mr. Jefferson tells larges stories," wrote Adams in his diary.33 Nontheless, throughout his life Jefferson was an ardent proponent of Don Quixote, insisting that his daughters Martha and Mary read it as part of their learning Spanish.

Benjamin Franklin, America's senior statesman, who organized the French and Spanish contributions to the American cause, listed Don Quixote in the first catalogue of his Library Company, in 1741. In his Autobiography,34 Franklin himself notes that he taught himself the French and Italian languages. "I afterwards with a little painstaking, acquir'd as much of the Spanish as to read their books also." Notably, Cervantes' Don Quixote.

Friedrich Schiller and Cervantes' Spain

The great Eighteenth-century German historian and poet Friedich Schiller dealt extensively with the disastrous rule of Phillip II, both in his historical writings, as well as in his truthful drama Don Carlos. Schiller addressed, in particular, Phillip's ineffectual policy towards the rebellion in the Low Countries, of first, doing nothing, and later, of bloody repression, but never attempting to engage his subjects to reach a working solution. In Don Carlos, the character Marquis of Posa tells Phillip what Cervantes must have wanted to tell the Hapsburgs more than a century earlier: "Give us back what you have taken from us. Thus become among a million kings, a king. ...Give to us the liberty of thought."32

There is no question that Cervantes and Schiller held similar views of the Hapsburg Phillip II. After mocking the elaborate preparations and ceremonies for the obsequies held in Seville on the death of Phillip II in 1598 ("I would bet that the soul of the dead man, to enjoy this place today, has abandoned his place of eternal rest"), Cervantes tags an additional triplet to his satirical sonnet, in which a braggart tells the narrator, the soldier Cervantes: " 'Everything you have said is true, and whoever says the contrary, lies.' And then, incontinent, he pulled his hat over his head, checked his sword, looked askance, left, and nothing happened."

Fidelio Table of Contents from 1992-1996