On Musical Placement

by Philip Ulanowsky

January 2016

A PDF version of this article appears in the November 20, 2015 issue of Executive Intelligence Review and is re-published here with permission.

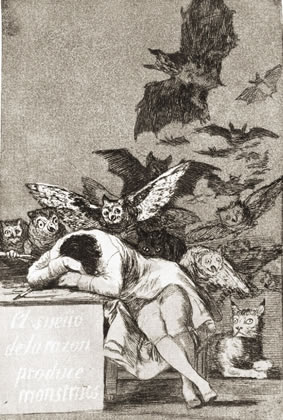

View full size Francesco Goya’s Capricho 43 (1797), captioned “The sleep of reason produces monsters.” |

November 8, 2015 —Over decades, Lyndon LaRouche has made a point of strategically redefining a word or term common to one or another pertinent branch of knowledge. To such terms—including common sense, manifest destiny, nege ntropy, and (musical) mode—he has recently added placement with respect to the language of Classical music.

In each case, LaRouche has presented his redefinition as an irony, an ambiguity to be resolved in the mind of his reader or listener, not merely to broaden, but to elevate that individual’s conception of the subject and of his or her own humanity. Throughout, these attempts to engage the mind of his audience on a higher plane, have shared the purpose of provoking a clearer, more beautiful appreciation of the science of creative human society. That society, itself, has been eroded virtually past existence by cultural degeneration over more than a century to date.

“Placement” has long had a meaning in vocal training, stemming from discoveries in the science of vocal production by Leonardo da Vinci and the Florentine school of beautiful singing—bel canto—which flowered in the Fifteenth Century Italian Renaissance and has at least survived through the present. It refers, in essence, to the means of using the voice optimally, minimizing tension and friction in the vocal chords and using the natural resonance in the various cavities of the head, in particular, to allow the freest, most well-projected quality.

This technical placement, within a naturally defined musical tuning, allows singers long careers (other considerations aside) by avoiding strains on the vocal apparatus which otherwise tend to shorten the life of the natural instrument. But, to what end? Countless orators and actors have studied and mastered the same subject; we find ourselves in a cultural wasteland nonetheless, in which each new generation comes into, and accepts as normal, an uglier, more bestial state of affairs in virtually every aspect of life. In a world besieged by war and terrorism, drug abuse, and social disintegration, can such an issue as placement have any significance?

The Sleep of Reason

The answer to this reasonable question, emerges from recognizing that words, logic, explanation—all fail in a society dominated by irrationality. One may recall from Spanish painter Francisco Goya’s 1797-98 Los Caprichos—a series of about eighty polemical prints revealing the ugly “secrets” of his society at that time—Plate 43, titled, “The sleep of reason produces monsters,” and captioned, “Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders.” When words lose their power to communicate, great art may carry its audience to that higher conception of humanity needed to become its better self.

Never has that need pressed us with more urgency than now. An honest look at the world around us suffices to show those “impossible monsters” on every side—both outside and in. It is thus to the power of great art that we look for a means to educate ourselves in the inexpressible, and to the power of music above all.

Placement, in LaRouche’s new casting, escapes the confines of technique, to embrace the power of music to inspire. Although its technical aspects play an essential role, vocal “plumbing,” no matter how good, can not generate the ideas upon which the future of civilization depends. (Technical skill in art may impress, but cannot substitute for ideas; technique must serve the higher purpose.) At the same time, any music worthy to be called great never stems from notes, any more than great poetry stems from words. In both, the true subject is unheard, an inexpressible idea in the mind of the composer, to be communicated to the mind of another individual, present only as that which generated the poem or the musical score. It lies behind the words and notes; it is the necessity bringing them into existence as momentary, partial expressions of a higher, creating process.

LaRouche’s new, ironic employment of placement, then, obliges the performer to submit every technical, as well as aesthetical, consideration to the service of communicating a composition’s insightful, universal idea, rejecting any sensual effect, no matter how appealing, which does not contribute to the strongest possible evocation of that idea in the audience. Without every effort to concentrate this power of art, our society will remain in the clutches of the debased “entertainment” and the profoundly pessimistic view of humanity it engenders, that have allowed us to walk so far down the path of failed civilizations past.