Virginia Opera Performs Verdi's Rigoletto

By Gabriela Ramírez-Carr

October 2010

Rigoletto, Melodramma in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi

Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, after Victor Hugo's play “Le roi s'amuse”

Virginia Opera at George Mason University

Conductor: Peter Mark

October 2010

Classical tragedy in the tradition of Homer, Aeschylus, Shakespeare, and Schiller, is not a romanticized “therapy session” where a flawed personality deals with his or her personal shortcomings. Daytime television may take delight in airing the dirty laundry of a celebrity, but classical drama must bring into focus the cultural roots of the unfolding tragedy. How could a population, which sees a crisis on the horizon, continue to march straight into its own demise? How could the captain of the Titanic, when told of an iceberg directly in its path, give orders to increase speed? How could present day America, faced with unprecedented industrial shut-downs and mass layoffs continue down the path of more deregulation, globalization, and even give bailouts to many of those who caused the problems?

In a well crafted and well presented work, the audience cannot leave the theater or opera house without examining the popular opinion and world outlook of the society that produced these flawed beliefs. It is precisely for this reason that great classical culture is so critical, especially during challenging times, hopefully preparing the audience to better examine its own cultural shortcomings and thus improving mankind.

It is also from this perspective that Virginia Opera's otherwise potentially beautiful production of Rigoletto was so off the mark. Marc Astafan, the stage director, unfortunately brags in his notes in the program guide, that he “can't get [his] head around monumental themes, universal ideas, or metaphors.” For Astafan the true tragedy of this Verdi opera is rooted in “a father's intense, deep and yet overbearing love for his daughter...[a]nd how that love destroys them both.” According to the stage director, apparently there is no problem with having a depraved society as long as no father tries to protect his daughter from this dehumanizing existence! Every classical dramatist would be turning in his grave, not just at Mr. Astafan's outlook, but that our society has been so culturally dumbed-down that his simplistic views could be so easily accepted, even on a major university campus!

Verdi's Mission

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) became a beloved national hero because he was so committed to use his art to uplift his people, unify his nation, and win independence from Hapsburg controlled Austria. His work would give voice to this Italian patriotism and even help create a national identity centered around great culture and a love for truth and beauty. Verdi was a regular attendee of the most advanced cultural and political salon in Milan where the Italian translators of Schiller and Shakespeare (Andrea Maffei and Giulio Carcano respectively), also attended and they became close friends and collaborators. In this period, in the 1840's, every single opera by Verdi contained a line, a chorus, or sometimes a mere gesture that inspired a patriotic response in the audience. The chorus in the 1842 opera, Nabucco, “Va pensiero,” for example, became the unofficial national anthem. It is for this reason that the censors, doing the dirty work for their Hapsburg oppressors, were instructed to scrutinize every musical note and each word for any politically coded messages.

Traditionally opera houses did not dim the lights during performances since so many patrons entered with the musical scores and wished to follow the opera in minutiae. These were not only the music aficionados interested in the latest musical innovations, but also the Italian patriots, who wanted to challenge any changes made by the censors. Even the smallest alteration could spark loud, spontaneous demonstrations from the audience and sometimes even forcing an end to the performance. The opera houses became the front lines of Italian nationalism and the audience would even throw bouquets of flowers of the national colors. (The police often stepped-in and forced the use of Austria's colors instead, however, predictably, the singers refused to pick-up these symbols of foreign oppression, provoking an even more intense response from the audience).

Shakespeare, Schiller, and Mozart

Verdi was very influenced by Shakespeare and Schiller and based several operas on their works. Verdi even said that he read translations of Shakespeare over and over again “from a very young age.” Although Rigoletto is based on a play by Victor Hugo and not Shakespeare, it is considered one of Verdi's most Shakespearean masterpieces. In Act I Rigoletto sings “Pari siamo,” which many consider a near Shakespearean soliloquy. Never before in Italian opera had characters been given such complex personalities, and even Verdi considered this among his most revolutionary works. He does not include any large chorus nor grand finale but has created a true rogue's gallery of dramatis personae, void of any hero who might muster sympathy from the audience.

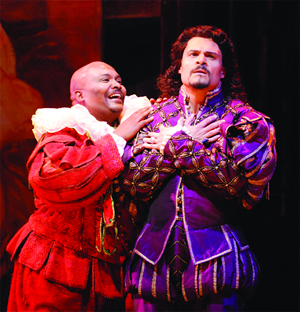

Photo Credit: Anne M. Peterson. Baritone Fikile Mvinjelwa as Rigoletto and Tenor Aurelio Dominguez as the Duke of Mantua. |

Verdi also used his “much studied” Don Giovanni by Mozart, especially in his dance in the opening scene (which our stage director, Marc Astafan, chose to delete). It is here, as the curtain rises, where the audience must see the seeds of the tragedy. Verdi has a small band playing music on stage, not in as a light festive dance, but rather a scene depicting all the corruption and frivolousness of the court, and it is here that the court jester, Rigoletto, is introduced as the true stage manager of all the depravity. When Count Ceprano becomes suspicious of the Duke's intentions with his wife, it is Rigoletto who takes great pleasure in insuring that the Count (and everyone else) knows fully what dishonor awaits the wife. As the Duke sings “Questa o quella,” the orchestra should seamlessly take over from the band on stage in a very Mozart-like maneuver. When done correctly this degenerate scene should be grating to the audience, especially since it just followed the very chilling prelude.

Like Mozart before him, Verdi's interest is the dramatic interplay between the characters. These are not unconnected chess pieces stranded on a stage while the orchestra pounds out a seemingly endless theme by Wagner. Verdi is able to keep a continual flow in the music, yet it is constantly changing in what he called a “series of duets.” Verdi's music changes to tell the story of each character and reflect his or her state of mind.

One of the greatest achievements in all Italian opera is the quartet in Act III, “Bella figlia dell' amore,” where the Duke, Maddalena, Rigoletto, and Gilda all simultaneously voice completely different themes yet Verdi is able to musically unite all the elements without compromising its emotional complexity. Victor Hugo, who originally went to court to stop Rigoletto from being performed in Paris, later admitted that Verdi improved his play and was won over by this single quartet, saying that it would be impossible to have these four voices simultaneously speaking on a stage, yet singing in an opera made complete sense.

Virginia Opera's Production

The Virginia Opera Company rarely disappoints in its recruitment of high caliber (and often very young) talent and this October, 2010 production of Rigoletto presented at George Mason University was no exception. The most memorable was the South African baritone, Fikile Mvinjelwa, as Rigoletto, who so easily filled the theater with his deep rich tones. He has sung at the New York Met but according to the program guide he is famous across South Africa for having sung for Nelson Mandela and President Mbeki. He has been singing since he was a child but because of Apartheid, a career in opera was never a possibility until age 26. Since then he has devoted his life to this art form and has developed tremendous vocal abilities. His acting could use some refinement, however, with a voice like his, I would be glad to have him return in any title role.

Photo Credit: Anne M. Peterson. Baritone Fikile Mvinjelwa as Rigoletto and Soprano San-Eun Lee as Gilda |

Another favorite with the audience was the Korean soprano, Sang-Eun Lee, as Gilda. It seemed that every time she was on stage she set the standard of excellence for all the others to follow in both singing and acting. She made her part, and really the entire opera come to life. Tenor, Aurelio Dominguez, playing the Duke of Mantua, clearly started-out with a voice which sounded like it did not have a chance to warm up. Using a very determined “mind over matter” approach, however, he overcame some mechanical difficulties and by the time of his “La donna e mobile,” he was able to deliver a quality voice and world class acting.

My consistent complaint against bass Nathan Stark, who played Sparafucile, is that the opera company needs to give him much bigger roles. He was spectacular when I saw him as the Commendatore in Mozart's Don Giovanni in the Virginia Opera's GMU performance in April. The placement and control over his voice give him an ample, developed, lush voice that can easily reach the last seat in the last row of the auditorium--even on the lowest of notes. Please stop hiding this guy! The baritone from Philadelphia, Kevin Moreno, played an excellent Marullo, and sings everywhere from Asia to Austria. The biggest surprise of all was the youngest cast member, the baritone Wesley Evans, a sophomore at Christopher Newport University, who played the role of Count Ceprano. His deep, rich voice gave him the confidence to perfectly fit in with the other, more experienced cast members. The role of Maddalena, was played by mezzo-soprano Audrey Babcock, who was able to combine a gorgeous voice with a seductive stage presence. Last but not least I saw Peter Mark conduct the Virginia Opera production of the “Barber Of Seville” in April, 2009 where he did a very fine job keeping everything together. Again with this production of Rigoletto he was masterful at keeping everyone in pace and balanced. I might further note that with his orchestral work, as the storm scene grew in intensity, I was so drawn into the moment that I remember thinking that I hoped my car windows were rolled-up! Mr. Mark should also be applauded for his work in recruiting and training young talent.

This production had all the necessary resources for a spectacular production if it weren't for the misguided directing of Marc Astafan. What a terrible waste of some great young talent.