This Week in History

December 15-21, 1773:

Boston's Patriots Hold a Tea Party in the Harbor

December 2013

"Voted, that this body will oppose the vending of any tea sent by the East India Company to any part of this Continent, with our lives and fortunes." So read the declaration passed by the 1,000-person Town Meeting at Faneuil Hall in Boston on Nov. 5, 1773. What could possibly have motivated such a strong stand against buying tea—was it poisoned? In a sense, it was. The story of the Boston Tea Party of Dec. 16, 1773 begins with the British Parliament's passage of the Stamp Act.

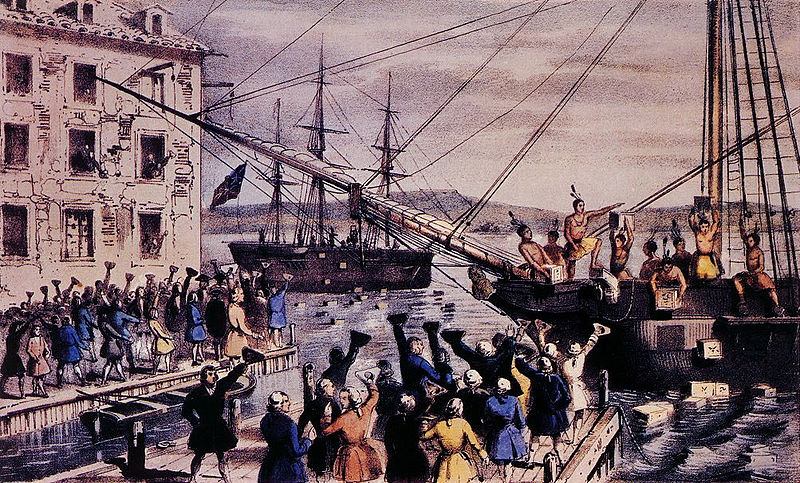

This 1846 lithograph by Nathaniel Currier was entitled "The Destruction of Tea at Boston Harbor". |

After the end of the French and Indian War in 1761, a war which had also been fought in Europe and Asia under the name of the Seven Years War, Great Britain acquired a vast empire. Trying to recoup some of the expenses of the war, the British oligarchy decided that the American colonials should bear part of the burden. Never mind that Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts had spent considerable sums on behalf of Britain and had never been paid back.

First came the Sugar Act, which fixed the price of molasses and limited the American molasses trade to the British West Indies, which could not possibly meet the American demand nor absorb the exports the colonies used to pay for the molasses. Then came the Stamp Act, which went into effect in 1765. This tax on licenses, publications, and legal papers sparked protests, including the Virginia Resolves, which were endorsed by most of the other colonies.

Then the Massachusetts Legislature sent out a call for a Congress of all the colonies to meet in New York to consider united action. That body produced a Declaration of Rights and Grievances, stating that only the colonies themselves could levy taxes on colonists. That statement caused an Englishman who was living in America to write home, contrasting "the remarkably pliant and submissive disposition of the inhabitants of Bengal," with that of the frisky American colonials.

The British East India Company, which was fast becoming the controlling factor in the British Empire, was already developing plans to tame the Americans into submission. It was dealt a setback, however, by massive American demonstrations against the Stamp Act and a partial boycott of British goods. British merchants and manufacturers became alarmed, and the new Rockingham Ministry repealed the Stamp Act. However, American joy at the repeal was quickly tempered by Parliament's refusal to repeal "The Declaratory Act," which allowed Britain to pass restrictive laws and levy taxes on the American colonies. A very specific Parliamentary pronouncement stated that the right to tax the colonies had always existed and would exist for all time.

When the Ministry of Charles Townshend, better known as "Champagne Charlie," came to power in 1767, a new attempt was made to force the colonies to admit that they had the "right" to be looted by the British Empire. The Townshend Acts taxed imports from Britain such as paper, lead, glass, paint, and tea. But there was a new and very threatening element embedded in the Townshend Acts, which the colonists did not take long to recognize. The Writs of Assistance legalized by the acts were blank search warrants which could by used by Royal agents at their pleasure, and anyone could be dragooned to help in the searches.

The Townshend Acts also established an American Board of Customs Commissioners in Boston, whose members were directly answerable to the Royal Treasury. Ostensibly, these members were to use the funds to defend the colonies, but the phraseology of the act stated that they would defray "the Charge of the Administration of Justice, and the Support of Local Government." Thus, the colonies would lose not only any fiscal control over their activities, but their self-government as well. Men who were responsible to the Crown and East India Company would control local government and the courts.

Again, the colonies united in protest, and in February 1768, the Massachusetts Legislature published a Circular Letter to the other colonies, stating that the Townshend Acts established taxation without representation, that colonial representation in England was impossible, and that the very idea of making colonial judges and governors independent of the electorate was intolerable. The new Prime Minister, Lord Hillsborough, furious over the Circular Letter, dissolved the Massachusetts Legislature.

Not content with that, Hillsborough sent a large flotilla of the British fleet, loaded with British Redcoats, to police Boston and ensure that Royal officials could carry out their tax-farming duties. Parliament also threatened to transport any American protesters to England for trial, and the colonies answered with a much larger boycott against British goods. In 1770, the Townshend Acts were repealed, but one subversive tool of empire was left intact, and that was the tax on tea.

In 1773, the East India Company's stock on the London Exchange dropped from 280 pounds to 160 pounds, and the company was facing bankruptcy. Parliament obligingly granted the company a tea monopoly for the American colonies, in order to put a dent in the surplus of over 17 million pounds of tea sitting in warehouses in England. The price of the tea was dropped to well below that of Dutch tea, which the Americans were smuggling into the colonies, but the 3-cent tax was left in place. Even with the tax, the price of the tea was so low that the East India Company was confident that the Americans would give in to the temptation to break their boycott.

Four merchant ships loaded with tea were dispatched to Boston, and six more headed to other American ports. The Americans knew that political and economic slavery to the British Empire was riding on those ships, and they prepared accordingly. The first tea ship, the "Dartmouth," arrived on Nov. 28, but the Boston Town Council demanded that the tea be returned to England. Two more ships arrived over the next two weeks; the final ship never appeared because it was wrecked off Cape Cod.

The three sea captains were willing to return the tea to England, but Royal Gov. Thomas Hutchinson sent a letter to Boston stating that by law he could not allow the ships to leave Boston until they had disposed of their cargoes. Hutchinson had appointed several of his relatives to be consignees for the tea shipment. As Boston patriot leader James Otis had said, "A very small office in the customs in America has raised a man a fortune sooner than a government." The British troops at Boston's Castle Island, commanded by Col. Alexander Leslie, were ordered to transport their artillery on some of the British warships to the outer harbor, in order to be able to fire on any tea ship that tried to leave.

In this seemingly impossible situation, Samuel Adams and Dr. Joseph Warren developed a daring plan that was touched with humor. On Dec. 16, a crowd of 5-6,000 people met at Old South Meeting House to determine what to do with the 348 chests of tea on the three ships. One last attempt was made to convince Hutchinson to release the ships to return to England, but he sent a reply, which arrived as darkness was falling, stating that the tea would be unloaded on schedule.

At this, Samuel Adams told the crowd that, "This meeting can do nothing more to save this country." The statement was a pre-arranged signal, and it was answered by a war-whoop from a man at the back of the crowd who was dressed as a Mohawk Indian. The cry was immediately answered by other "Indians" outside the building. About 200 such Bostonians, smeared with paint, soot and grease, marched two-by-two to Griffen's Wharf and divided into three groups, one for each ship. They were dressed as Mohawks as an answer to Hutchinson, who had publicly stated that Sam Adams was the "Chief of this tribe of Mohawks," referring to the Sons of Liberty.

What happened next was described by George Hewes, one of the participants. "As soon as we were on board," wrote Hewes, "Lendall Pitt, my commander, appointed me the boatswain, and ordered me to go to the captain and demand of him the keys to the hatches and a dozen candles. I made the demand accordingly, and the captain promptly complied, but requested me to do no damage to the ship and rigging. We then opened the hatches and took out all the chests of tea. First we cut and split the chests to thoroughly expose them to the water, and thus broken, we threw overboard every tea chest to be found in the ship; while those in the other ships were disposing of the tea in the same way, at the same time, it being about three hours from the time we went on board. We were surrounded by British armed ships, but no attempt was made to resist us."

No American was allowed to take even a pinch of tea for himself, and the two "Indians" who gave in to temptation were treated roughly. Many young apprentices of 12 or 13 years of age had slipped away from their masters and wanted a part in the proceedings. They were given the job of stomping into the mud any of the tea which had washed up on the flats near the ships. This proved a difficult task, for the piles of washed-up tea were large, and many of these exhausted boys did not reach home until midnight.

Sam Adams had arranged for the returning "Mohawks" to be serenaded by a fife and drum band on the dock. As they marched into town, British Adm. Montagu, who had been visiting friends near the harbor, leaned out of a window and shouted, "You'll have to pay the fiddler yet! You have had a fine pleasant evening for your Indian caper, haven't you?" And, indeed, the British East India Company reacted with fury when they heard about the Boston Harbor teapot.

The Parliamentary reaction, labelled the "Intolerable Acts" by the colonists, contained everything the empire had wanted to do to America but couldn't up until that time. The port of Boston was closed, even to ferry boats, and the royal capital was moved to Salem. The city was under martial law, and supplies could reach it only over a narrow neck of land. Another act of Parliament stated that it was aimed at "better regulating the government of Massachusetts Bay and purging their constitution of all its crudities." This meant that the governor's council, the attorney general, judges, sheriffs and justices of the peace were to be named by the Royal Governor, and juries were to be selected by a Crown-appointed sheriff. Town meetings could only be held when the governor consented, and had to follow an approved agenda.

But the British made the same mistake with the Intolerable Acts as they had made with the tax on tea, for they tended to see others in their own image. They assumed that Americans would be tempted by the low price of tea to selfishly break the boycott and sell their birthright for a mess of potage, but it did not happen. Again, the British counted on the other colonies to shrug off the Intolerable Acts as affecting only Massachusetts. And again, this did not happen, for the other colonies realized that what was done to Massachusetts could also be done to them. All the colonies pledged aid to starving Boston, and the colony of New York went so far as to pledge a food supply for the next ten years. The most important result of the Intolerable Acts, fatal to British Empire plans for America, was the call for a Continental Congress to be held in Philadelphia in September 1774.

The original article was published in the EIR Online’s Electronic Intelligence Weekly, as part of an ongoing series on history, with a special emphasis on American history. We are reprinting and updating these articles now to assist our readers in understanding of the American System of Economy.