This Week in History

February 12-18, 1791:

'Doing Something Difficult': —

Peter Cooper and the Public Benefit

February 2012

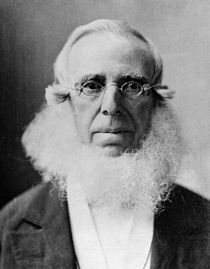

Peter Cooper.

|

Several outstanding Americans from various centuries share a Feb. 12 birthday with Abraham Lincoln, and one of them, Peter Cooper, is associated with the speech which Lincoln himself felt had gained him the Presidency. That was the Cooper Union speech in New York in 1860, but it was only the first of two Cooper Union meetings which played an important role in Lincoln's ability to save the nation.

Peter Cooper was born in 1791, when George Washington was President, and died in 1883, a year after Franklin Roosevelt was born. During this long span of time, he contributed to the public good in an amazingly varied number of ways. Peter's father was a veteran of the Revolutionary War, as was his mother's father. In 1799, Peter's father held him up above the crowd so that he could see George Washington's funeral parade wending its way down Broadway, in New York City. Peter also got to see Thomas Jefferson riding up to the building where Congress was meeting.

Because his family was poor, Peter received only three terms of schooling. He had to go to work at a young age, and learned hatmaking, brickmaking, grocery clerking, cloth shearing, and carriage manufacturing. Even as a boy, his great curiosity about how things worked led to his invention of a mechanical washtub for his mother, and to his being able to make shoes for his family after he found one on the street and took it apart. At the age of 17, he invented a machine for mortising carriage wheels, never patented it, and noted in 1879 that his design was still "mortising all the hubs in the country."

Cooper described himself in a memoir as "never satisfied unless I was doing something difficult—something that had never been done before, if possible." As a young man, Cooper invented an endless-chain device for propelling boats. First demonstrated successfully on the East River, the device was then offered to DeWitt Clinton, who wanted to use it on the Erie Canal. The plan was quashed because the farmers along the canal had been promised the rights to sell feed for the mules that pulled the canal boats.

Peter Cooper then bought a glue and isinglass factory, and resolved to build it into the best factory in the world. His glue became world-famous because it had such reliable uniformity. He once refused to raise the price as high as the large demand for it would have warranted, saying that, "The world needs this thing." He stayed in the glue-manufacturing business for over 30 years, for it enabled him to both work on his myriad inventions and become an entrepreneur in other industries.

First, Cooper joined other investors in buying a large plot of land across from Fort McHenry on Baltimore Harbor, and branched out into iron production, especially for the emerging railroad industry. The commissioners of the new Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had pushed the construction of the roadbed through hilly country, and now found that their curves were too sharp for any known engine. Cooper came to the rescue by designing and building a legendary locomotive called the "Tom Thumb."

In August of 1830, the little brass engine had a successful run, with six men on the engine and 36 men on the passenger car. The train achieved a top speed of 18 miles an hour. This frightened the owners of the local stagecoach lines, who challenged the engine to a race. Cooper's engine was beating the horse-drawn carriage when his pressure device failed, and by the time he fixed it, the horse had an insurmountable lead. Despite the defeat, the railroad was extended westward, and by 1834, the B&O had seven locomotives, 34 passenger cars and a thousand freight cars running as far as Harper's Ferry. The race between the "Tom Thumb" and the horse-drawn carriage became an American legend when it was circulated as a Currier & Ives print, diplomatically showing the two contestants running neck-and-neck.

In 1845, Cooper moved the ironworks to Trenton and built it into the largest rolling mill in the United States. In addition to railroad rails, the plant turned out iron beams for the new iron-framed, fireproof buildings that were beginning to appear in the major cities. The firm received orders for iron beams to frame the new dome of the U.S. Capitol, as well as for the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia. Then, in 1854, Cooper was one of the six investors who met at the home of his next-door neighbor, Cyrus Field, to form the company which would lay the under-ocean cable for the first Atlantic telegraph.

Peter Cooper considered the crowning achievement of his life to be the founding of "The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art." As a young man, he had resolved that if he should prosper, he would devote a portion of his money and energy to assist young men in the pursuit of knowledge. As a member of the Common Council of New York City, Cooper had been a Trustee of the Public School Society and, afterwards, a Commissioner of Education. But, in 1859, he realized his life's dream by founding the Cooper Union, building it a large, fireproof building, and offering free classes in science, art, and engineering to working men and women. The building also provided an extensive library and a large hall in which public lectures were given.

After reading the published transcripts of the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858, Cooper and his friend William Cullen Bryant, who were both Jeffersonian Democrats, became more and more convinced that Abraham Lincoln should become President of the United States. In 1860, Cooper and Bryant invited Lincoln to speak in New York, and convinced Cooper's circle of entrepreneurs to attend the speech at the Cooper Union. On Feb. 27, 1860, Bryant presided at the podium, Cooper's friend David Dudley Field led Lincoln to the platform, and Peter Cooper looked on from the audience. The result of Lincoln's masterful speech was that many eastern Democrats helped vote him into the Presidency.

When Lincoln faced a difficult reelection battle against Gen. George McClellan in 1864, Cooper organized a rally of pro-war Democrats at Cooper Union to support Lincoln and the continuation of the war. One account says that a group of Boston Unionists came to New York, and went straight to Peter Cooper as someone who, "in an ugly squall, never said, 'Go, boy, and reef that topsail,' but always, 'Come, boys, let us do it.'" One of the Bostonians asked Cooper for letters of introduction, but Cooper answered, "There's no time for letters or palavers; just get into my buggy."

Cooper then drove the Bostonians at a reckless pace all over the city. "From door to door we drove," reported one passenger, "through the crowded streets, stirring up one timid friend, holding back the next who wanted some other method, insisting with all against delay, or doubt, or change of plans, till in half the time anyone else would have taken, Peter Cooper, with his big Union at his nod, had arranged for the great meeting."

The meeting was held on Nov. 1, a week before the election, and the New York Herald reported that, in response to a "trumpet call," all the leading Jacksonian or War Democrats were present. When "Major General Dix, Francis B. Cutting, Peter Cooper, and other well-known, staunch supporters of the Democratic Party in the days of its pristine glory made their appearance on the platform," they were greeted with such an enthusiastic reception, continued the article, that it must have done wonders to decide the waverers in the packed audience.

After the end of the war, and Lincoln's assassination, Cooper did not waver in trying to carry out Lincoln's programs. Immediately after the war, he pleaded for monetary support for disabled veterans and their families, and also supported the Southern Relief Association which had been organized to care for the destitute in the former Confederacy. He reacted strongly to the attempts to disenfranchise the freed slaves, making a public address in 1872, in which he advocated keeping the Republicans in power, because the contest over slavery "is not yet over." He stated that the country was still in danger from those who "once levied war against it with bullets, and who now seek to overthrow it with ballots."

In 1880, at the age of 89, Cooper had the pleasure of serving as the focus, along with a reproduction of the "Tom Thumb," of Baltimore's 150th anniversary parade. But age did not stop his campaigns for the improvement of the general welfare. He lobbied the U.S. government to set up industrial schools, such as the Cooper Union, across the country; campaigned to get the Federal government to build the Northern and Southern Pacific Railroads; and proposed that the government should establish a program of large-scale public improvements that would also provide employment for thousands of Americans. The last proposal would be fulfilled by a future President who was but one year old when Cooper died in 1883.