This Week in History:

October 21-27, 1693: Lord Thomas Fairfax Becomes an American and Helps the Colonies Break Through to the West

October 2012

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron, 1612-1671.

|

Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron, 1693-1781.

|

October 22, 1693 was the birth date of Thomas Fairfax, the Sixth Baron Cameron and heir to the estates in England and Virginia of a very interesting family. The Fairfaxes were known as statesmen and soldiers who also showed talent in the literary field. The third Lord Fairfax, also a Thomas, became Commander of the New Model Army in 1645 during the English Civil War. He was superceded by Oliver Cromwell, whom Fairfax did not support because he suspected Cromwell was heading for a military dictatorship.

Fairfax resigned his commission when he was ordered to invade Scotland, and he also resigned his appointment as a judge at the subsequent trial of King Charles I, when he realized that the king's execution had been predetermined. This Thomas Fairfax was also responsible for saving the priceless contents of the Bodleian Library when it was threatened with destruction during the Civil War.

The Thomas Fairfax born in 1693 was only sixteen years old when his father died. He succeeded to the title of Baron Cameron only a few days before he was to leave for college at Oxford. According to contemporary accounts, most students at the Oxford of that time lived a riotous, pleasure-seeking life, but although Thomas Fairfax was sociable, he studied seriously and became known for his accomplishments in literature. It is said he contributed an article to "The Spectator," a well-known literary magazine which also printed many articles by Jonathan Swift.

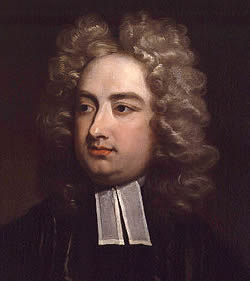

Jonathan Swift, 1667-1745.

|

Queen Anne, 1665-1714.

|

Thomas's mother, Lady Fairfax, was active in Whig circles in England, and the unofficial leader of those circles was Jonathan Swift, recognized today for his brilliant satires, but less known for his activities as a statesman. Swift and his circle had succeeded, during the reign of Queen Anne, in freeing England from the "perpetual war" policy of the Venetian Party and its leader, the Duke of Marlborough. Swift was also able to see that the colonies of Virginia and New York/New Jersey received able governors who promoted the development of the colonies, and supported their attempts to break through the Appalachian Mountains to the fertile lands of the Ohio Valley.

When Thomas Fairfax left college, Swift's circles were battling a new threat. This was the return to power in England of the Venetian Party's Robert Walpole, a man so corrupt that he was popularly known as "Bob Booty." Walpole had coined, so to speak, the phrase "Every man has his price," and he proceeded to demonstrate it by bribing the Commons, the Lords, and even the King. Walpole was also an inveterate enemy of any attempt to develop the American colonies beyond an existence as coastal depots for exporting raw materials to England.

As soon as Walpole became prime minister in 1721, Thomas Fairfax, an anti-Walpole Whig, was thrown out of his post as Deputy to the Treasurer of the King's Chamber. Fairfax was able to obtain a commission as Cornet in the Royal Regiment of Horse Guards, commanded by the anti-Walpole Marquis of Winchester.

During this time, Fairfax was trying to administer his family's English estates while dealing with a clone of Robert Walpole in America.

This second embodiment of greed was Robert "King" Carter, who had been appointed many years previously to oversee the Fairfax Proprietary in Virginia.

|

A survey map of the Northern Neck, 1732.

|

This proprietary, like William Penn's in Pennsylvania, was nominally under the British Crown, but was administered by the Fairfax Barons under a grant from the King. The Northern Neck Proprietary, as the Fairfax Grant was called, extended from the western shore of Chesapeake Bay up the peninsula between the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers. In 1688, King James II had amended the grant to state that the grant went westward as far as the "first heads or springs" of those two rivers.

This was a very crucial statement, for the Fairfax lands extended northwestward like an arrow toward the Ohio River, and that was where the colonists would have to go to be able to extend their settlements across the continent. But King Carter had marked out huge tracts of Fairfax lands for himself, his family, and his cronies, and used them as a speculative investment, not for the development of farms and towns. As a result, settlers wanting to move west had to leapfrog over Carter's huge and empty holdings, leaving the pioneers with no infrastructure or military support immediately behind them. And the Virginia Council, of which Carter was a member, was pressing London to declare that the Potomac River only extended to its confluence with the Shenandoah River, not to the high Allegheny Mountains.

From 1735 to 1737, Lord Fairfax visited Virginia, and arranged for surveys to be made of his grant. In this he was aided by former Governor Alexander Spotswood, another member of the Swift circle who had brought Virginia out of the feudalist backwardness imposed upon it by Venetian Party toadies like King Carter and his ilk. Another collaborator of Spotswood was his fellow iron-manufacturer Augustine Washington, the father of three-year-old George Washington. After a survey of the Fairfax Grant was made by two teams, composed of surveyors appointed by the Virginia Council and by Fairfax, the Council still insisted that the Potomac ended at the Shenandoah. Fairfax returned to London in order to break the stalemate.

It was not until 1745 that the King confirmed that the Fairfax grant ran westward into the high Alleghenies. Thomas Fairfax then turned his English properties over to his younger brother and moved to America permanently.

At first, he stayed with his cousin and new land agent William Fairfax at Belvoir, a home just south of Mount Vernon. There George Washington's older brother Lawrence lived with his wife, a daughter of William Fairfax. Lord Fairfax took much interest in the now teen-aged George Washington, and hired him to survey portions of his lands.

In 1752, Fairfax moved just beyond the Blue Ridge to the Shenandoah Valley, where he built a house called "Greenway Court." This was not an impressive mansion, for Fairfax lived simply, dressed simply, and spoke plainly. He assured the hardy pioneers who had come down the Valley of Virginia from Maryland and Pennsylvania that no man should lose his land just because he was poor. Unlike the king, who required all rents and taxes to be paid in coin, Fairfax would accept any kind of product from settlers who bought parcels of his land. In issuing some deeds, he only required a turkey or partridge paid at Christmastime. He also set up "manors," which were not the feudal kind, but were large tracts of land where people too poor to buy land could rent it and have rights to it through three generations.

Lord Fairfax also supported the plans to set up a settlement near the forks of the Ohio River. He participated in negotiations with the eastern Indians at Winchester in 1753, and tried to recruit as many men as possible for the expedition, ultimately led by George Washington, to support the Ohio River Settlement. Again, when General Braddock and his army were sent to evict the French Forces who had taken over the English fort at Pittsburgh, Fairfax's home was at the center of preparations for the march. All through the dark days of the French and Indian War, when most of the Shenandoah Valley settlers fled in terror eastward back over the Blue Ridge, Fairfax remained at Greenway Court to help organize the resistance against French and Indian incursions.

When the American Revolution began, Lord Fairfax was in a difficult position. He favored the American cause against the policies of the Venetian Party, whose East India Company was now completely running the British Government. But he could not speak out in public, for it might mean that his brothers and sisters in England might lose their land and income. Because anyone who did not abjure their loyalty to King George III were subject to double and then triple taxes, Fairfax was penalized very heavily for his enforced silence.

Finally, former General Charles Lee, who lived near Fairfax, sent a petition to the Virginia House of Delegates on behalf of the inhabitants of Berkeley County, asking that Fairfax not be considered as a Loyalist. Lee classified Fairfax's case as being "unexcepted in the United States," and said that he and his neighbors considered it as their "indispensable duty to bear testimony of his uniform friendly conduct in the most public manner toward the liberties and friends of America from the commencement of this anxious struggle."

Lee's petition further stated that Lord Fairfax had helped stabilize the Continental currency by ordering his collectors to receive the paper dollars at six shillings apiece, which was much higher than they had been valued at before. Fairfax had also been active in the exchange of prisoners, and had furnished any aid which the Virginia Government had requested.

Lord Fairfax lived long enough to receive word that George Washington's forces had defeated General Cornwallis at Yorktown. In 1785, Virginia cancelled the Northern Neck Proprietary, but by that time Fairfax's policies had fostered a growing population, and in just a few more years, Americans would be building towns and plowing fields in Ohio.

The original article was published in the EIR Online’s Electronic Intelligence Weekly, as part of an ongoing series on history, with a special emphasis on American history. We are reprinting and updating these articles now to assist our readers in understanding of the American System of Economy.

View large size

View large size