This Week in History

May 12-18, 1876:

President Ulysses S. Grant Opens

The Philadelphia Centennial Exposition

May 2013

Library of Congress.

The American Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia, 1876..

|

Just as dawn came on May 10, 1876, the bell in the tower of Philadelphia's Independence Hall began to ring, and it was immediately echoed by the Liberty Bell and all the church bells of the city. They rang out the news that a century of American independence was about to celebrated with the opening of Philadelphia's Centennial Exhibition. It was an international exposition of progress in the arts and sciences, the first ever held in this country, and so President Ulysses S. Grant was joined at the opening ceremonies by Emperor Dom Pedro of Brazil, representing the other nations which had sent their discoveries and products to Philadelphia.

At the end of the American Civil War in 1865, many of the world's governments had assumed that the United States would undergo a long period of economic and psychological exhaustion before recovering from the devastating four-year conflict. But under President Abraham Lincoln, the states loyal to the Union had embarked upon such an expansion of scientific and technological innovation, that when the war was over, the United States had been transformed into a world power.

The wonderful consequences of following the principle of the general welfare, extending its benefits to many generations beyond, was never more evident than at the Centennial Exposition. One hundred and twenty-eight years later, we can still look back and see the solid basis of our "modern" society being formed, as reflected in the discovery of new scientific principles, and even many of the same products that we rely upon today.

The exposition had been planned over a period of three years, with Centennial Commissioners from each state serving on the planning committees. The exhibit was spread over 236 acres in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park, and consisted of 190 buildings, the largest of which, the Main Building, covered 21 acres of ground. The seven major buildings offered exhibits on Mining and Metallurgy, Manufacturing, Education and Science, Art, Machinery, Agriculture and Horticulture. Thirty-one foreign nations sent exhibits, and by closing day on Nov. 10, almost 10 million people had walked through the automatic, self-registering turnstyles which had been set up at 106 different gates.

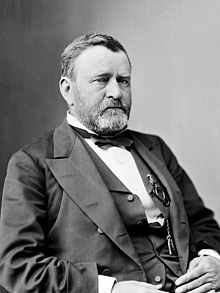

Ulysses S. Grant.

|

The Centennial's Bureau of Transportation had anticipated the problems that might stem from transporting such large numbers of people to and from, as well as within, the exhibition. They coordinated many modes of travel to the fair, including discounted railway excursions, steamboats, carriages, and horse-drawn streetcars. Within the park, there was a narrow-gauge steam railway that ran on five-and-a-half miles of track, and an elevated monorail, carrying up to 60 people, which shuttled across the Belmont Ravine. At the Belmont Hill Tower, visitors could travel vertically by using an elevator which carried 40 people at a time up to a bird's-eye view of the exhibition.

On opening day, more than 100,000 people stood in front of Memorial Hall to hear a 1,000-person chorus sing John Greenleaf Whittier's "Centennial Hymn," followed by a welcoming speech by President Grant. The President and Dom Pedro then walked to Machinery Hall, where George Corliss, an inventor and industrialist from Rhode Island, showed them his personal gift to the exhibition, the Corliss Double Walking-Beam Steam Engine, whose 30-foot flywheel, weighing 56 tons, was designed to supply the power for all the machinery in the hall. When Grant and Dom Pedro each turned a wheel, energy was routed through 75 miles of belts and shafts, driving 8,000 different machines. The watching crowd broke into spontaneous and delighted applause.

Three-fourths of those machines had been produced in America. They included a 7,000-pound pendulum clock by Seth Thomas that acted as the control for 26 other clocks that were located throughout Machinery Hall. There were many models of the sewing machine, which Americans by this time considered an "older" invention, but also a large display of locomotives and equipment included George Westinghouse's new air brake, just introduced on the Pennsylvania Railroad. Massive rotary presses of the Bullock and Hoe companies turned out thousands of copies of the New York Herald and Philadelphia Times for the exhibition visitors. On a smaller, but very important scale, the new "type-writer" machine of Christopher Sholes, manufactured by the Remington Arms Company, was demonstrating how printing could be brought to offices and homes.

Probably the most important displays in Machinery Hall, upon which most of the others depended, were the products of William Sellers of Philadelphia and Pratt & Whitney of Hartford, Connecticut. These were America's foremost manufacturers of machine tools, the machines that produce other machines. These iron machines could shape metal in many ways, making possible high-speed mass production with interchangeable parts. In the United States Government Building nearby, workers and machines from the Springfield Arsenal demonstrated the system by assembling rifles from identical parts machined to a thousandth of an inch tolerance.

Another display demonstrated steel's use as a structural material, and showed how the steel arches of Captain James Eads's bridge across the Mississippi at St. Louis had been formed and joined. In the same hall was a section of wire cable for John Roebling's famous Niagara suspension bridge, then the largest in the world, but about to be surpassed by the cable for the new Brooklyn Bridge. Another group of machines, using Charles Goodyear's new invention, turned out rubber boots and shoes for visitors. And there was a strange, eight-foot-long machine, which looked like the inside of a huge piano, which was George Grant's "Calculating Machine," an American version of Englishman Charles Babbage's calculator. And from Langen and Otto in Germany came an internal combustion engine, which Americans also were struggling to perfect.

Agriculture Hall displayed models of Cyrus McCormick's Reaper-Binder, the Adams Power Corn Sheller, the Buckeye Mower and Reaper, and the Sweepstakes Thresher. There, too, were breakthroughs in food production and distribution, such as packaged dry yeast and canned goods. A leading example was provided by frontier surveyor Gail Borden's condensed milk, which had been such a boon to the troops during the Civil War.

The exposition's directors at first hoped to keep the exhibits open on weekday evenings, but the fear of possible fire from gas lighting caused them to declare a 6:00 p.m. closing time. Thomas Edison's "multiplex" telegraph, capable of sending several messages at once over the same wire, was exhibited at Philadelphia, but it would take another three years for the development of his first commercially practical incandescent lamp. Just before the Centennial Exhibition opened, Edison had built and opened his research facility at Menlo Park, New Jersey, and by 1881, when he designed New York's Pearl Street Plant, the first central electric light power plant in the world, he had developed a complete system of electricity distribution, including generators, motors, light sockets, junction boxes, safety fuses, and underground conductors.

When the exhibition opened in May, Alexander Graham Bell was nowhere to be seen, nor had the invention he was working on been entered in the electrical section. Although he had patented the telephone in March, he was working on improvements through the spring, and on May 10 was presenting a lecture and demonstration at the Boston Athenaeum for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He gave his first public demonstration at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on May 24, with a clock-spring transmitter telephone in the auditorium which communicated with one in a nearby house. On June 14, Emperor Dom Pedro visited Bell at the Boston School for the Deaf to observe his "Visible Speech" method for teaching the deaf to speak, but Bell never mentioned the telephone.

Finally, when scientists from all over the world were arriving in Philadelphia to judge the exhibits, Bell's father-in-law arranged to have the telephone displayed in the Massachusetts Education and Science exhibit. Bell called his telephone the "Centennial iron-box receiver," and when he withdrew 100 yards away and sang into his transmitter, one of the judges, British scientist Sir William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, could hear him clearly. At this point, according to Bell's account, Sir William shouted, "Where is Mr. Bell? I must see Mr. Bell!" Thomson rushed to the gallery where Bell was still speaking lines from Shakespeare's plays into the transmitter, and Dom Pedro took his place, repeating Hamlet's "To be or not to be" soliloquy as it came over the wires. Dom Pedro, too, then led half the spectators at a very rapid pace toward Bell's position, as scientist Elisha Gray took over the receiver and repeated, "Aye, there's the rub," as the crowd cheered.

In his closing speech at the Centennial Exposition, General Joseph Hawley stated that "The world knows a great deal more about us now than it ever did before." More appropriate for our era would be a phrase from President Grant's speech at the opening ceremonies: "Whilst proud of what we have done, we regret that we have not done more."

The original article was published in the EIR Online’s Electronic Intelligence Weekly, as part of an ongoing series on history, with a special emphasis on American history. We are reprinting and updating these articles now to assist our readers in understanding of the American System of Economy.