This Week in History:

July 8 - July 14, 1776

July 2010

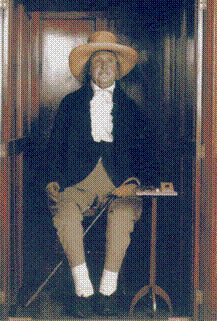

The mummified corpse of Jeremy Bentham, British imperialist and mortal enemy of human rights and dignity. |

The major audience for the Declaration of Independence was not domestic, but those nations from which the American colonies were seeking recognition, commerce, and alliances in the war against the British Monarchy. Would they treat with the newly declared independent nation, despite the virulent opposition of the British?

Indeed, the Declaration was explicit in terms of its international focus. First, from the first paragraph, it couched its argument in relation to the "opinions of mankind" as a whole, not simply to citizens of the colonies. Second, the final substantive sentence laid out what the emerging United States wished to exercise: "full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do."

There was no question but that the British would do everything possible to prevent recognition. Already, by July 13, Ambrose Serle, the secretary to Britain's chief General, Lord Howe, had written in his diary that "a more impudent, false and atrocious Proclamation was never fabricated by the Hands of Men." Four copies made their way to London, and by mid-August, it began to be published in the London press, followed by Edinburgh, Dublin, and Leiden (Holland).

In September the Declaration was published in Copenhagen, Denmark, and Florence, Italy. A German translation appeared in Basel, Switzerland in October.

The nation the Founding Fathers were most interested in, of course, was France, England's age-old enemy, and their hoped-for military ally. But in France the reaction was considerably delayed. The first of the two copies sent to American representative Silas Deane was "lost," and the second arrived in November 1776. France's recognition of the new republic did not occur until February 1778, after General Washington's Army had won a significant victory over the British troops at Saratoga, New York.

As for the British, they did not recognize American Independence until the Treaty of Paris was hammered out in 1783. Even an official British comment on the Declaration might be construed as acknowledging the existence of what they did not wish to acknowledge.

But the British did commission a response to the Declaration of Independence, which was entitled "Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress," and was sent in 500 copies to the British troops in America. The author of the document, which was signed by a young lawyer named John Lind, was actually none other than that old scalawag Jeremy Bentham. Bentham's argument was a direct assault on the idea of natural law, and the idea that God's law could be implemented through government. He said: "They [the Declarers—ed.] perceive not, or will not seem to perceive, that nothing which can be called government ever was, or ever could be, in any instance, exercised, but at the expence of one or other of those rights" to life, liberty, or the pursuit of happiness.

Bentham's argument, not surprisingly, is a reflection of that legal positivism which is espoused today by the dominant school of legal thinking, and by the likes of Hobbesian politicians like Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski. Bentham insisted that mankind has no natural rights, and that the only source for claiming any rights at all was positive legislation. In other words, morality was to be banned from politics altogether.

In reality, the battle between the natural law principles of the Declaration of Independence, and the British concept of positive law, continues to this day. The British oligarchy—and those who have allied themselves with it—still finds the American republic, as consituted on its principled foundations, to be the major challenge to the form of oppression they wish to exert, whether that oppression be exerted through monarchies, various forms of dictatorship, or a public-opinion-dominated democracy. Until Americans themselves restore the natural law principle, as established in the Declaration and the Constitution, to their practice, the outcome of the conflict remains in doubt.

This article was originally published in the EIR Online’s Electronic Intelligence Weekly as part of an ongoing series on history, with a special emphasis on American history. We are reprinting these articles now to assist our readers in understanding of the American System of Economy.