This Week in History

November 22-28, 2015

From Inchon to the Yalu - The Case of the Purloined Intelligence:

MacArthur vs. the British Empire’s World War Threat, Part IV (November 25, 1950)

China Launches Full-Scale Intervention

By Gerald Belsky

General Douglas MacArthur. |

This article is the 4th in the series by the author on the lessons to be learned from the command of General Douglas MacArthur versus the British empire's geopolitical manipulation. Here are links to the first three articles in this series: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

On the evening of November 25, 1950, Chinese forces launched a sudden major attack against General Walton Walker’s Eighth Army in its center and eastern flank, as it moved forward in the western part of North Korea in coordination with General Almond’s X Corps on the eastern side of North Korea, in General MacArthur’s giant “envelopment and compression attack.” This was designed to be a final push to the Yalu River on the Manchurian border, either to end the Korean War by mopping up remaining North Korean forces assisted by Chinese “volunteers”, or to “spring the trap” of potentially hidden massive Chinese forces by what MacArthur later characterized as a “reconnaissance in force”.

The day before Walker’s offensive had kicked off, on November 24, MacArthur had toured the front lines and, within earshot of the press, told General John Coulter, the IX Corps commander, whose troops held the center of Walker’s Eighth Army, “If this operation is successful, I hope we can get the boys home by Christmas.” This remark, made “half in jest but with a certain firmness of meaning and purpose”, according to his chief aide Major General Courtney Whitney, was made with the intention of assuring the Chinese that he had no intention of permanently stationing U.S. troops in Korea, assuring the Eighth Army troops themselves which had done most of the fighting in Korea that they were not going to be fighting indefinitely in Korea in the midst of an oncoming winter and would be back in Japan for Christmas, and also assuring Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Omar Bradley, that the division he requested for use in Europe at the Wake Island meeting after the Korean War had wound down would soon be available.

After the Chinese attacks the next few days and into December forced the withdrawal of UN forces southward, this remark of MacArthur’s, according to Whitney, “was completely twisted and misinterpreted as a powerful propaganda weapon with which to bludgeon MacArthur.” His offensive to the Yalu was subsequently attacked in the major U.S. press and continues to be attacked in most history books today as the “Home by Christmas offensive.” [1]

MacArthur actually had never predicted definitely that the “boys would be home by Christmas”, only that if the offensive “succeeded”, meaning that if it defeated the North Korean army and discovered that the Chinese did not intend a full-scale offensive, then the Eighth Army would be withdrawn from Korea, and be back in Japan for Christmas. If, however, his offensive discovered that the Chinese in front of him were, in fact, part of a full-scale offensive, then the offensive would succeed in a way he did not state publicly at the time, in “springing the trap”, and forcing the question of how to deal with “a whole new war”.

But the idea that he believed his offensive would definitely succeed in ending the war, because he ignored the potentially deadly Chinese threat, is a deliberate distortion of what MacArthur himself had earlier stated, both publicly and in answers to a question by the Joint Chiefs of Staff on the level of threat he faced from the Chinese after the initial assaults by Chinese forces in late October-early November.

To the Joint Chiefs, he had insisted that his offensive northward to the Yalu must proceed, because the only way to determine the level of Chinese threat, and determine if the Chinese intended a full-scale offensive was through the further “accumulation of military facts,” in other words, the “reconnaissance in force”. Otherwise, MacArthur told the Joint Chiefs that he thought a full-scale offensive at this stage of the war when the North Korean army had been virtually defeated made no sense. He would soon discover, however, under what conditions such a Chinese offensive would, in fact, occur.

MacArthur Foresaw the Threat

On November 6, 1950, General MacArthur issued what he would describe as a “special communiqué” to identify for the American people the situation that he faced in the Korean War:

“The Korean War was brought to a practical end with the closing of the trap on enemy elements north of Pyongyang and seizure of the east coastal area, resulting in raising the number of enemy prisoners-of-war in our hands to well over 135,000 which, with other losses mounting to over 200,000, brought enemy casualties to above 335,000, representing a fair estimate of North Korean total military strength. The defeat of the North Koreans and destruction of their armies was thereby decisive…. The present situation therefore is this: While the North Korean forces with which we were initially engaged have been destroyed or rendered impotent for military action, a new and fresh army faces us, backed up by a possibility of large reserves and adequate supplies within easy reach of the enemy but beyond the present sphere of military action. Whether, and to what extent these reserves will be moved forward remains to be seen and is a matter of gravest international significance. Our present mission is limited to the destruction of those forces now arrayed against us in North Korea with a view to achieving the United Nations’ objective to bring unity and peace to the Korean nation and people.”

The above report makes clear that MacArthur knew before the Chinese forces struck hard on November 26 that massive Chinese intervention was, indeed, possible, but he also knew that the only way he could find out the truth of the matter was to move forward. The problem he faced, however, was not simply Chinese intervention, but that the orders under which he operated told him to continue to advance in the face of “major Chinese Communist units” only if he had a “reasonable chance of success”. His orders from Washington read thus:

“In the event of the open or covert employment anywhere in Korea of major Chinese Communist units, without prior announcement, you should continue the action as long as, in your judgment, action by forces now under your control offers a reasonable chance of success. In any case, prior to taking any military action against objectives in Chinese territory, you will obtain authorization from Washington.” [1]

In other words, MacArthur was being told to continue his attack only if he believed he could defeat the Chinese forces he faced with the forces he then commanded, so that if he faced far more Chinese forces than he had, with the threat of far more Chinese forces in reserve, MacArthur should stop the attack. Thus, MacArthur had to be careful in his phrasing of the threat he faced in reports to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Had he said explicitly that he faced massive Chinese intervention, he would have been told to halt his advance, but, in reality, he didn’t know without advancing forward.

The last sentence in the order was not entirely honest, since it implied the possibility of authorization of attacking Chinese territory if major Chinese forces attacked, but the decision had already been made that no attack on China would occur, in order to keep the war strictly “limited”, although MacArthur was never specifically informed of that fact. However, he was well aware that the intention was to keep the war in Korea limited, as part of a military buildup against Russia, and that the military-political establishment in Washington foresaw the trap of getting involved in a war with China, as a diversion from the real war, with Russia!

General Omar Bradley |

General Omar Bradley, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff after MacArthur’s relief, would attack MacArthur’s demand that the U.S. bomb Manchuria with the famous statement that MacArthur wanted to “involve us in the wrong war, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy. The views of General Omar Bradley before the Chinese intervened are summarized in his “Autobiography” written with his collaboration by Clay Blair:

“…Facing the prospect of global war at any hour, to the JCS Korea was comparatively a minor irritation. We still held to the view that the sooner we got out the better and that, above all, we should not let the war ‘spread’ to involve us in a general war with Red China. Moscow was the real enemy. Korea was a diversion; a war with China would be the ultimate diversion.”[2]

The same day that MacArthur issued his special communiqué warning of the threat posed by the fresh army facing him, as well as the warning of “destruction of his command” if he couldn’t bomb the bridges over the Yalu, detailed below, American intelligence agencies concluded, according to the US Army official history of the Korean War, that “between 30,000 and 40,000 Chinese were now in North Korea and that as many as 700,000 men including 350,000 ground troops could be sent into Korea to fight against the United nations forces. These Chinese forces would be capable of halting the United Nations advance by piecemeal commitment or, by a powerful all-out offensive, forcing the United Nations to withdraw to defensive positions farther south. The report concluded with a significant warning:

“A likely and logical development of the present situation is that the opposing sides will build up their combat power in successive increments to checkmate the other until forces of major magnitude are involved. At any point the danger is present that the situation may get out of control and lead to general war.”

Of course, we now know that many of those Chinese ground forces were already in Korea, but the only way for MacArthur to discover this reality was to advance to the Yalu. MacArthur himself admitted at this time that “such forces will be used and augmented at will, probably without any formal declaration of hostilities.” According to the Army history, “He emphasized that if the Chinese augmentation continued, it could force the United Nations Command to perform a ‘movement in retrograde.’” [3]

Since these warnings were issued at the beginning of November, after the initial Chinese attacks, and the recognition that their forces were increasing, why is it insisted today by most historians that the full-scale offensive by the Chinese on November 26 came as such a surprise?

Furthermore, and most importantly, as we shall demonstrate, the British had reserved for themselves the right to be consulted in any decision to counterattack China, and thus exercised veto power.

The Bombing of the Yalu Bridges

Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Lovett in 1951. |

|

On the same day that he issued his November 6 communiqué warning of the threat of new and fresh forces facing him, MacArthur planned to have his air forces bomb the bridges across the Yalu across which he knew large Chinese forces were crossing. When Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Lovett (who had been chief executive of Brown Brothers before it merged with Harriman, shortly after which Wall Street’s Brown Brothers Harriman had helped install Hitler with British backing) found out about these plans, he started an emergency process which led to orders being sent to MacArthur to stop the planned bombing.

When Lovett discussed stopping MacArthur from bombing the bridges with members of the State Department, Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs Dean Rusk, according to an official US Army history of the Korean War, “pointed out that the United States had promised the British Government not to take action which might involve attacks on Manchuria without consulting the British”

Dean Rusk, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs. |

The Joint Chiefs of Staff’s order to stop the bombing consequently included a direct reference to the British veto power:

“One factor is the present commitment not to take action affecting Manchuria without consulting the British. Until further orders postpone all bombing of targets within five miles of the Manchurian border.”

After a very forceful protest in the strongest terms, in which MacArthur warned that “men and materiel in large forces are pouring across all bridges over the Yalu from Manchuria”, and that, under these conditions, he insisted, quite correctly, “This movement not only jeopardizes but threatens the ultimate destruction of the forces under my command”, MacArthur urged that the JCS reconsider its order to prevent the bombing of the Yalu bridges, and bring the issue up to President Truman to reconsider. In order to stop this buildup of Chinese forces threatening him, MacArthur stated, “The only way to stop this reinforcement of the enemy is the destruction of these bridges and the subjection of all installations in the north area supporting the enemy advance to the maximum of our air destruction.”[4]

The result of MacArthur’s warning of the “ultimate destruction” of his command, and the implied threat that he could go public with this threat, was to rescind the order not to bomb within five miles of the Manchurian border, and to give him permission to bomb the South Korean end of the Yalu bridges. But as MacArthur would later bitterly complain: How do you bomb half a bridge? He could not bomb any part of the bridges beyond halfway across the Yalu. Under his new orders, his air forces could not violate any Manchurian airspace, which meant that his bombers had to approach from the south in a very predictable way, allowing anti-aircraft guns and Soviet planes to more easily attack them. In any case, Chinese commanders had built underwater pontoon bridges, and within a month the Yalu began to freeze, so the bombing of the bridges was no longer effective and was suspended. But the desire to not even carry it out, and have a five mile effective “demilitarized zone” south of the Yalu, indicates the intent to wage a “limited,” futile war in Korea. The question is, of course, to what purpose?

The same British veto applied, it should be pointed out, when Secretary of State Acheson was forced, by MacArthur’s demands and ample international legal precedent, to request permission of Britain and other UN allies to carry out “hot pursuit” of Soviet planes which crossed the Manchurian border to attack U.S. bombers. The British said no, as did other allies, and the issue was never brought up again.

Leaks of Intelligence

As we have stated, MacArthur insisted for the rest of his life that the Chinese would never have intervened in force unless they had been given the intelligence that MacArthur would be restricted in what he could do in counterattacking: Not bomb above the Yalu, not bomb Manchurian cities, not attack their industrial centers, not impose a naval blockade, and not treat an attack by China as “an act of war”, but keep the Korean War strictly limited. In his Reminiscences, MacArthur has the following to say about this leak of intelligence, and its consequences:

“That there was some leak in intelligence was evident to everyone. Walker continually complained to me that his operations were known to the enemy in advance through sources in Washington. I will always believe that if the United States had issued a warning to the effect that any entry of the Chinese Communists in force into Korea would be considered an act of international war against the United States, then the Korean War would be terminated with our advance north. I feel that the Reds would have stayed on their side of the Yalu. Instead information must have been relayed to them, assuring them that the Yalu bridges would continue to enjoy sanctuary and that their bases would be left intact. They knew that they could swarm down across the Yalu River without having to worry about bombers hitting their Manchurian supply lines.”[5]

MacArthur’s confidante, Major General Courtney Whitney, wrote, under MacArthur’s direction, the following about these intelligence leaks:

“Furthermore, any assumption that our security was vulnerable to compromise rests upon other evidence than Red China’s decision to commit major force to battle on the peninsula. On several occasions General Walker complained bitterly to MacArthur that his operational plans, which were always telegraphed to Washington under the highest secrecy classification, were being leaked to the enemy, thereby giving the latter a constant awareness of his battle strategy. The exact source of such leaks mattered only insofar as knowledge of it would provide the basis of their being plugged…

“Finally on December 30, 1950, at possibly the most crucial phase of the war against Red China in Korea, one of MacArthur’s top-secret dispatches to Washington giving intelligence on the order of battle was in part published verbatim in the Washington Post under the byline of a prominent columnist.” [The Post had editorially denied that such leaks of intelligence could have given China the assurances to enter the war, since such a claim, it lamented, “amounts virtually to a charge of treason against responsible civilian and military leaders in Washington.”- GB]

MacArthur vigorously expressed his concern in a message to Washington on January 6.

“The leakage of highly classified messages dispatched to the department from this headquarters and subsequently published in the press either textually or in substance gives me increasing concern,” he message read. “…An intolerable situation is created under which an irresponsible columnist…achieves access to the secret dispatches of this command dealing with military operations against the enemy. His very acquisition of such secret dispatches is unquestionably a criminal act for which he should be vigorously prosecuted in the public interest.’ ”[6]

The fact that MacArthur is attacking the Anglo-American Establishment’s Washington Post for publishing the classified information about his military command which its “prominent columnist” was given, demonstrates that he knew he wasn’t simply dealing with what many have assumed to be mere “communist spies”. He complained that Washington did nothing to plug the leaks, nor prosecute this columnist; but he obviously knew that high level circles in Washington had, in fact leaked the information! Couple this fact, with his charge that assurances had been given China that it could attack in Korea without being attacked, and it is clear that MacArthur believed there was a link between these assurances and the continued leak in intelligence. Once again, we must ask: To what end?

Franklin Delano Roosevelt. |

The “prominent columnist” — or perhaps “calumnist” is more appropriate — identified by MacArthur was Drew Pearson, whose “Washington-Merry-Go-Round” column in the Washington Post was a constant source of gutter slander and planted material. Before Pearl Harbor, Pearson worked with British Intelligence to build support for America entering the war, since the British Empire had decided that their puppet Hitler was a threat. But during the war, Pearson tried to slander FDR, by claiming that America was turning its back on Soviet Russia and trying to “bleed it white”. President Franklin Roosevelt himself held a press conference to refute these charges and called Pearson a “chronic liar”. MacArthur, himself, when U.S. Army Chief of Staff, had sued Pearson for slander, but dropped the suit when Pearson blackmailed him by threatening to publish embarrassing love letters to a young Filipino woman.[7]

In Pearson’s column of December 30, 1950, entitled, “MacArthur Puzzles Pentagon”, Pearson quotes from MacArthur’s intelligence chief General Charles Willoughby’s various intelligence reports on his estimates of the Chinese forces he is facing, and the U.S. response to these forces. Pearson quotes Willoughby’s confidential estimate that the United States was facing 283,000 Chinese and 150,000 North Korean forces, in order to contradict MacArthur’s public statement that he faced “a bottomless well” of Chinese forces, ready to cross the border.

The most important aspect of Pearson’s leak, which was clearly given him by circles in the Pentagon (Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Lovett, who hated MacArthur with a passion?) was to attack MacArthur’s strategy of retreating in the face of the Chinese forces, in order to lengthen their supply lines, by forcing them to go further south. MacArthur had no intention of fighting a static war of attrition, as in the trench warfare of World War I, but to weaken the Chinese by forcing them south, attack their supply lines in Manchuria, and then fight a war of maneuver to outflank and envelop them from the north. However, the same Wall Street pro-British forces, which had wanted him to fight a static war in the “waist” of North Korea, and attacked him for going further north to “spring the trap”, now attacked him for going further south, instead of “standing and fighting” the Chinese, by “holding a line”.

View full picture Cecil W. Stoughton [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Journalist Drew Pearson in the White House Garden with President Lyndon Johnson, April 1964. |

Thus, Pearson writes:

“Another of Willoughby’s intelligence cables to Washington about mid-December is interesting: ‘Lack of CCF on Eighth Army front. Due to deep withdrawal executed by Eighth Army, it is evident that enemy, lacking any degree of mobility, has been unable to regain contact.’

“This is interpreted in the Pentagon as saying that the Chinese, lacking any means of transportation, were unable to keep up with the fast retreat of the Eighth Army. In other words, we failed to keep contact with the enemy, one of the fundamental rules of military strategy.”

Pearson attacks the UN retreat by stating that “the Chinese, according to Willoughby, lacked fire-power, air strength, artillery, could not travel with any speed, while their high command, being ‘stereotyped’, could not regroup easily to take advantage of the U.N. retreat.”

He concludes by attacking MacArthur’s press statements warning of the “bottomless well” of 500,000 Chinese forces he directly faced in Korea and available as reserves over the border, for the purpose of attacking MacArthur’s insistence that we can’t fight a “limited” war. Clearly, this intelligence was leaked to Pearson by circles in Washington who wanted to discredit MacArthur for opposing the use of the Korean War as a “limited war” in order to carry out the NATO military buildup. Here is how Pearson ends his slander:

“These are some of the facts which don’t show up in the press dispatches from Tokyo. The inescapable conclusion is that either Willoughby is wrong or the MacArthur press communiqués have been deceiving the American public.” [8]

In a New York Times statement, published on February 9, 1956, in response to the charges by Truman in his memoirs, which had been serialized in the Times, that MacArthur had misled him at Wake Island about the possibility of Chinese intervention, MacArthur insisted once again that a “spy ring in Washington” had “purloined” his intelligence, and that shortly after he had requested that this spy ring be caught and tried for treason, not only did Washington do nothing, but he was shortly relieved.[9]

MacArthur Attacks British Perfidy

Whom did MacArthur believe was behind the leaks of intelligence both to force the Chinese to enter the Korean War, and then to enable them to know U.S. orders of battle, to increase UN casualties, in order to keep the Korean war going, and attack MacArthur’s reputation at the same time? The British Empire! Without saying all that he knew, MacArthur in a “secret” interview released only a few days after his death in April 1964, accused the British of “perfidy” in setting him up in Korea. This points to the real “falsification of intelligence” by the British Empire in Korea, a method its agents, such as Tony Blair, have used in the more recent wars.

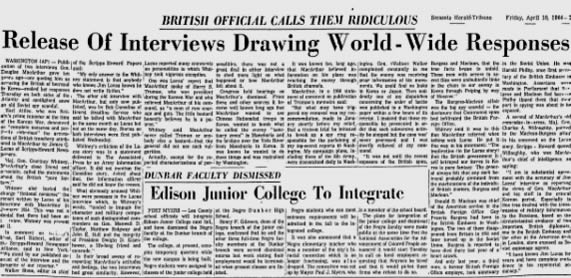

On April 8, 1964, three days after General MacArthur's death, Jim Lucas, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for his coverage of the Korean War, with the Scripps-Howard Newspapers, published notes from an explosive interview he had conducted with MacArthur ten years earlier in 1954, which he had vowed not to release until after the General's death. The interview, which included a key charge by MacArthur of “British perfidy” in Korea, as well as blunt and disparaging comments about political figures and other soldiers (He referred to Truman as “the little bastard” who “honestly believes he is a patriot”, but is “a man of raw courage and guts...a gutter fighter”), was covered throughout the United States and sent shockwaves around the world, especially in Britain. The article in the New York Times about this and some other “secret” interviews was entitled “MacArthur Blamed British For a 'Betrayal' in Korea.”

Jim Lucas' published memo of the interview included the following comments by MacArthur:

“1. On several occasions during the Korean War he had the Communists in the 'palm of my hand' and could have crushed them but was circumvented A) by the perfidy of the British and B) by constant harassment and interference from Washington. He referred to this as The Great Betrayal, a story he said was unmatched in history but 'will never be told while I am alive.'

“He said every message he sent to Washington and every message Washington sent to him was shown to the British by the State Department, and that, within 48 hours, was relayed by the British, either through India or through the Russian Embassy in London, to the Chinese Communists. Thus, he said, the Chinese Communists knew in advance every step he proposed to take. The Chinese Communists decided to come into the Korean War, he said, 'after being assured by the British that MacArthur would be hamstrung and could not effectively oppose them.' ”

Read the story This story ran in the Sarasota (Florida) Herald-Tribune on April 9, 1964. |

What made this charge so explosive is that MacArthur was not simply referring to what seemed like the obvious case of the British spy-ring of Philby, Burgess and Maclean (revealed later to include the Queen's Surveyor of Pictures Anthony Blunt), ostensibly Soviet agents, but actually to “Triple Agents”, who conveyed this intelligence to the Russians, and thence to the Chinese. (The British Government, in the wake of the spy scandal, continued to deny that the spies had leaked any valuable intelligence!) MacArthur, however, said “the British” rather to mean a deliberate British policy of betrayal, with the clear implication of State Department complicity. The so-called “spy ring”, all of whose members were part of the Bertrand Russell networks promoting world empire through nuclear terror, were simply the means of conveying the intelligence that the Empire wanted to use to play the United States, Russia, and China against each other.

According to the New York Times the day after this interview appeared,

“The British Embassy in Washington issued the following statement:

“British Commonwealth troops were serving in Korea at the time and it is unthinkable that the British Government would endanger the lives of its own soldiers by passing information to the Communist Chinese as is alleged in the article [by Mr. Lucas].”

Is it really “unthinkable” that the British Empire would sacrifice its own troops for what it considered a “higher purpose” – that of manipulating the United States, Russia and China to their own ultimate destruction?[10]

- To be continued-

Footnotes

[1] General Douglas MacArthur, Reminiscences, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 1964, pp 366-7

[2] General of the Army Omar N. Bradley and Clay Blair, A General’s Life: An Autobiography, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1983, p. 582

[3] James F. Schnabel, Policy and Direction: The First Year, (United States Army in the Korean War series), Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, DC, 1992, pp.244-245

[4] ibid, pp. 242-243

[5] MacArthur, pp. 374-375

[6] Major General Courtney Whitney, MacArthur: His Rendezvous With History, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1956, pp. 455-457

[7] Wikipedia entry, “Drew Pearson (journalist)”

[8] Drew Pearson, The Washington Merry-Go-Round: “MacArthur Puzzles Pentagon”, The Washington Post, December 30, 1950, p. B 9

[9] “Statement of General Douglas MacArthur in Response to Charges by President Truman”, The New York Times, February 9, 1956

[10] Texts of Accounts by Lucas and Considine on Interviews with MacArthur

MacArthur Blamed British For a 'Betrayal' in Korea - The New York Times, April 9, 1964

General Whitney, MacArthur’s confidante, lost his nerve once MacArthur was dead, and denied that MacArthur had ever made such comments, despite the fact that his own book which was written with MacArthur's notes and under his direction, attacked British influence in Washington and implied this very charge. Jim Lucas, who had interviewed MacArthur, called Whitney a “liar”.