This Week in History

November 9-15, 2014

Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery

Reaches the Pacific, November 15, 1805

by Colin Lowry

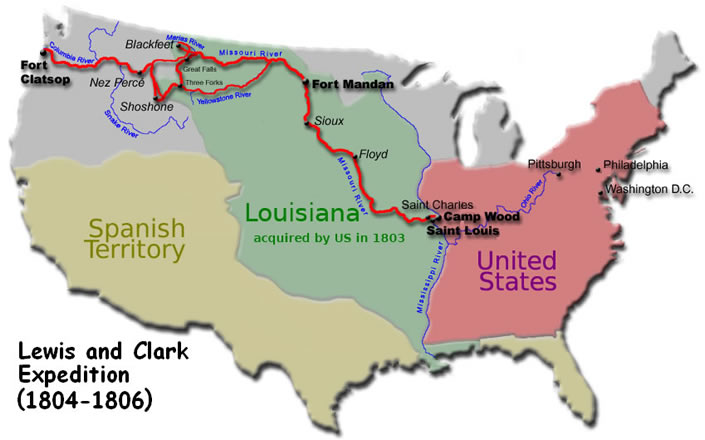

After a journey by land and by river of over 3000 miles, lasting 18 months, the expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark finally arrived at the mouth of the Columbia River, near Point Ellice, in present-day Washington State. From there they could see between Cape Disappointment and Point Adams, the open sea of the Pacific Ocean, which was the goal they set out to reach when they left St. Louis in May 1804.

|

In 1803, the United States bought the Louisiana Territory from France, more than doubling the size of the country’s land area, but very little was known about the lands west of the Mississippi River. The northern border with British Canada was not firmly established, and the Spanish claims in the west also complicated exactly where the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase really were. President Jefferson wanted to find the main rivers and possible water routes that could lead from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, then called the Northwest Passage, though no one knew if a continuous water route existed. The British had sailed into the mouth of the Columbia River in 1795, and had made some claims to the area, but had not built any settlements, as they were primarily interested in the fur trade in the North West, and of stopping the Americans from claiming the area. Their claim had never been recognized by the United States, as an American ship under the command of Captain Robert Gray had sailed into the mouth of the Columbia River from the Pacific Ocean, and had explored the surrounding land in 1792. With the Louisiana Purchase, the Americans needed to establish themselves in the North West, and attempt to settle the position of the northern border with Canada, as well as try to make treaties and trade agreements with the numerous Indian tribes who inhabited the area, to prevent the British from manipulating the Indians into attacking Americans.

The Corps of Discovery that Lewis and Clark were to lead, was a scientific, military, economic, and diplomatic mission, into vast uncharted land containing unknown native peoples. Jefferson’s orders to Lewis stressed the diplomatic approach he was to take with any tribes he encountered, writing that “in all your intercourse with the natives, treat them in the most friendly and conciliatory manner which their own conduct will admit; allay all jealousies as to the object of your journey, satisfy them of it’s innocence, make them acquainted with the position, extent, character, and peaceable dispositions of the United States, and of our wish to be neighborly, friendly and useful to them.” Lewis was also given instructions to arrange for influential Chiefs to be brought to Washington D.C., for negotiations, and that if the tribes desired it, their young people would be educated by Americans and taught science and useful arts.

The scientific work the expedition was tasked with, included exploring and mapping the rivers and main tributaries along the Missouri River, and of finding the route to link across to the Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean. Also, this was the first expedition in America tasked with studying, and sampling the native plant and animal species found along the way, as well as native American goods, tools, and symbolic artifacts from the tribes they encountered. Lewis and Clark also kept careful notes and descriptions of the cultural practices and appearances of all of the Indian tribes they met during the expedition, which provided the first understanding to the Americans in the east of what life was like for the Indians of the west.

At St. Louis, the expedition gathered the limited maps and reports from French and Spanish traders who had ventured up the Missouri River, and to the west. The first part of their river journey would be up the Missouri River to the north, all the way into present day North Dakota, to an area where the Mandan Indians had a permanent settlement. The expedition included about 30 men, including several experienced French traders, who spoke several Indian languages. Using several pirogue style boats, and a larger keelboat, it was possible to travel entirely by water to the Mandan village. Once there, the river split, and the branch leading west was rocky and difficult to navigate, making it necessary to use smaller canoes to continue. The Corps of Discovery arrived at the Mandan village, about 60 miles north of present day Bismarck, N.D., in late October, 1804. The Mandans were a peaceful tribe, that grew crops, and traded with other tribes, and with British and French traders operating from Canada. Living peacefully nearby, were the Minitaris, who had come from further west, and were rumored to know the crucial routes to the Pacific coast. Here the expedition would build its own quarters to stay for the winter, before heading west.

While at the Mandan village, a very fortunate set of circumstances brought two new members into the expedition, who would be crucial to its future success. A French trader named Charbonneau, who spoke Minitari, was hired by Lewis as an interpreter and guide. Charbonneau joined the expedition, only after convincing Lewis that he could bring along his young Indian wife, Sacagawea, who was pregnant with his child. Sacagawea was sold to Charbonneau by a Minitari chief, who told him she was a Shoshoni who was captured by a raiding party when she was a young girl, and brought back to live with his tribe. Both Lewis and Clark knew from their discussions with the Minitaris that the Shoshoni tribe lived at the edge of the great mountains where the trail across the divide to the Columbia River was surmised to be. The Minitaris also told Lewis and Clark that the Shoshoni tribe were great horsemen, and kept large numbers of horses and mules in their villages. Clark realized that to cross the mountains with most of their supplies, they would need to acquire horses from the Shoshoni, and this thought made him enthusiastically welcome Sacagawea as the only woman into the Corps of Discovery. Sacagawea gave birth to her son, named Jean Baptiste, in February 1805 at the Mandan village.

Beaverhead Rock, recognized by Sacagawea from her childhood, proved very helpful to the Lewis and Clark Expedition, for it meant her people, the Shoshones, were nearby. |

With the melting of the ice in the river in spring, Lewis and Clark sent the larger keelboat with many of the animal and plant samples, and copies of notes and maps, south down the river to St. Louis with a small crew. The remaining members of the Corps of Discovery would now push west into the unknown. Navigating the increasingly rocky river west was slow going, and required many portages. The territory saw an increase in the dreaded Grizzly bear, and several attacks nearly killed members of the expedition. Once in present day Montana, several forks split off from the main Missouri River, and to find which was the main branch often required splitting the group, and exploring up each one far enough to determine if the river branch was still going in the right direction, according to the descriptions given by the Indians to Lewis and Clark. After weeks of following the correct branch westward, they encountered the falls of the Missouri, and had to make a difficult portage around it. Finally coming to the area of the three forks of the Missouri River, in present day western Montana, Sacagawea told Clark she recognized the country, and expected that they might find the Shoshoni villages in only a few more days of travel. At the three forks, it was not immediately clear which river to follow, to get to the pass through the mountains that was described by the Indians. Lewis and Clark again split their parties, and each went along a different fork.

Supplies were running low, it was already July and very hot, and Lewis set out with a party of 4 men hoping to find the Shoshonis. Finding a worn trail heading into the mountains, Lewis saw an Indian riding a horse at a distance. He laid down his gun, and walked holding a blanket in his arms toward the rider, but when he got within 20 feet of the man, the Indian wheeled his horse and sped away. The next day, Lewis pushed further on along the trail, coming upon an Indian woman and her two daughters gathering roots. Surprised, one young girl started to run away, while the woman and the other daughter sat down, terrified, as if reconciled that they would die. Lewis put down his gun, walked up to the woman, and gently took her hand and raised her up, repeating words of greeting in Shoshoni that Sacagawea had taught him. He was so tanned by the sun that to show he was a white man, he lifted his shirt to show his white skin. This display calmed the woman, who then called her other daughter to come back. Lewis then gave them gifts, and in sign language asked them to take his party to their village. After walking a few miles toward the village, a band of 60 braves on horseback galloped up to Lewis and his party. Luckily, the Indian women explained to the braves and their chief that these white men were friendly, and Lewis and his party were welcomed by the chief, and allowed to continue to the Shoshoni village. At the Shoshoni village, Lewis found that the tribe had over 700 horses and some mules, and if his plan to cross the mountains to the west was going to succeed, he needed to barter for horses with the Shoshoni chief. None of his French guides spoke the Shoshoni language, so he had to wait for Clark and his party to come up the trail, after sending a few men to find them and show them the way to the village. Two days later, Clark’s party arrived, and when Sacagawea saw the Shoshoni chief, she realized he was her brother, and they both embraced each other and wept with joy. With Sacagawea able to interpret for Lewis and Clark, the negotiations went well, with the expedition gaining horses and a Shoshoni guide, who would help them cross the Bitterroot mountains, into present day Idaho, a territory that was controlled by the Nez Perce tribe.

The Shoshoni guides had explained the only way west was by land over the mountains, over what was known as the Lolo trail, used by the Nez Perce. This portion of the journey turned out to be the most challenging, as they encountered snow covered mountains, steep canyons, and could find no food in the Bitterroot range. They avoided starvation by eating some of the horses that had died from exhaustion and starvation. Almost starving themselves, the men crossed 160 miles of seemingly endless snowy peaks, and stumbled upon a Nez Perce village in a high prairie of western Idaho. Luckily, the Nez Perce were not hostile, and fed and nursed many of Lewis and Clark’s men back to health. These Nez Perce had not seen white men before, as their language was not known to any of the guides, so the expedition had to count on Sacagawea to communicate with the chiefs. From the Nez Perce, they learned that rivers that flowed into the Columbia were not far away, and two Nez Perce guides agreed to help the party build new canoes, and to take care of the expedition’s remaining horses, returning them to Lewis and Clark for the return trip east the next year.

Fort Clatsop. |

Moving westward along what is now called the Snake and then the Clearwater rivers, they finally found the junction of the upper Columbia River. Once on the Columbia, there were two large falls to get around, and then on to the Pacific Ocean. Reaching present day Astoria, Oregon on November 14, a huge storm and giant waves forced the party to pull the boats out of the river. The next day was clear, and landing on the north shore of the Columbia river, they could see the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean. They had completed a journey no other white men had done before, and they would now camp for the winter, building a series of wooden structures they called Fort Clatsop, south of present day Astoria, Oregon. The return trip back to St. Louis would take until September, 1806, where the Corps of Discovery was welcomed as heroes. The knowledge, reports and stories they brought back with them would change the course of the development of the United States.