This Week in History

June 15-21, 2014

June 21, 1779

235th Anniversary!

Spain Declares War on Britain, Helps America Win its Independence

Here is the dramatic story of Spain’s part in establishing the United States of America.

This remarkable text – “Spain’s Role in the American Revolution”– is extracted from “Spain’s Carlos III and the American System” by William F. Wertz, Jr. and Cruz del Carmen Moreno de Cota, published in Fidelio, Volume 13, Number 1-2, Spring-Summer 2004. http://www.schillerinstitute.org/fid_02-06/2004/king_carlos_3_spain_reduced.pdf

Spain’s Role in the American Revolution

www. spanisharts.com

Francisco Goya y Lucientes, “Carlos III in Hunting Costume,” 1786-88. |

Although the role of Bourbon France in supporting the American Revolution is highly celebrated, the role of Spain under Carlos III is less known. As we have documented, Carlos III, Europe’s other Bourbon monarch, was firmly persuaded beginning with his experience in Naples, that Britain was his natural enemy, and that her defeat was absolutely necessary. In this, Carlos was not motivated by merely strategic designs, but rather by a commitment to promoting the General Welfare not only of the people of Spain and the Spanish possessions, but of the North American colonies as well. As was the case with France, Spain under Carlos was open to the republican reforms expressed by the movement led in North America by Benjamin Franklin.

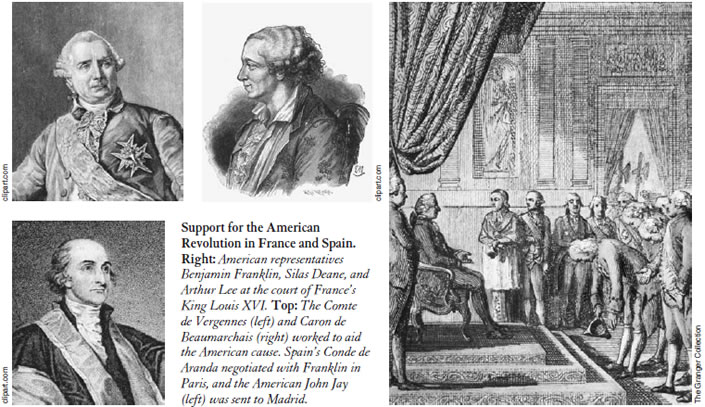

In 1774, France’s Louis XV died. Louis XVI, his grandson, came to power, and with him the ministers Anne Robert Jacques Turgot and Charles Gravier, the Comte de Vergennes. When the American Revolution began, Vergennes strongly advocated that the revolution be secretly aided, whereas Turgot maintained that the true interest of France was to remain perfectly neutral. Even before the arrival in Paris of the American representatives Silas Deane, Benjamin Franklin, and Arthur Lee, France had adopted Vergennes’ plan, and Turgot had been dismissed.

A month before the signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, France and Spain had set about giving financial assistance to the revolutionaries. Grimaldi wrote a letter from Madrid on June 27, 1776 to Aranda in Paris, in which he told Aranda that he had informed Carlos III of “secret discussions with the Comte de Vergennes on the subject of the aid which His Crown proposes to make available to the rebels in the British colonies and the other assistance they plan to afford them in secret. . . . His Majesty applauds the actions of the French Court and deems them well suited to the common interests of Spain and of France. . . . His Majesty has accordingly instructed me to send Your Excellency the enclosed credit of one million ‘livres tournois’ to be used in this enterprise. . . . Your Excellency is hereby granted leave to discuss with the Comte de Vergennes the best method of utilizing this sum of money and how best to ensure that it reaches the rebel forces.”[26]

Silas Deane had come to Paris to see Vergennes. He was soon in communication with Aranda, the man who had expelled the Jesuits from Spain, and who had been appointed Spanish Ambassador to France by Carlos III in 1773.

Both Spain and France were, in principle, of like mind to aid the American Revolution against the British. France sent Beaumarchais to London and de Bonvouloir to North America. Spain’s Minister of the Navy, José de Gálvez, ordered the Governor of Havana to send agents to Pensacola, Florida and to Jamaica. Dispatches between Vergennes and Grimaldi discussed the conquest of Portugal, Minorca, and Gibraltar, all strategic assets of the British. Aranda considered an attack on Ireland.

In 1776, there was a ministerial upheaval in Spain. Floridablanca was recalled from his embassy at Rome to replace Grimaldi, who had resigned in November 1776. Grimaldi became ambassador to Rome. Beaumarchais headed the Roderique Hortales et cie., founded to aid the American revolutionaries. Spain and France contributed one million livres each to form this company.

The American George Gibson visited the Governor of Louisiana, Luis de Unzaga y Amezaga, to request a commercial treaty. By December 1776, Unzaga had received arms, munitions, clothing, and quinine, with orders to send them to support the Revolution. Powder and guns were also sent to them from Havana and Mexico. On Oct. 26, 1776, Benjamin Franklin arrived in France. Arthur Lee, who was in London, joined him in Paris. Deane, Franklin, and Lee met with Aranda on Dec. 29, 1776, and then later on Jan. 4, 1777. They proposed an alliance among the American revolutionaries, France, and Spain. Aranda was in favor of a direct alliance.

Franklin was ready to go to Spain to make a treaty of alliance, as authorized by the American Congress, but Aranda dissuaded him from going at that time, knowing that Spain was not yet ready for a formal treaty. Franklin, nonetheless, asked Aranda to communicate the following proposal to Carlos III, based on a resolution of the Congress (Dec. 30, 1776):

Should His Catholic majesty wish to make an alliance with the United States and wage war on Great Britain, the United States shall undertake to support any attack He may make on the port and city of Pensacola, always provided that the United States shall continue to be permitted to sail freely up and down the Mississippi and to make use of the port of Pensacola. The United States shall declare war on the King of Portugal (assuming that it prove true that the said King of Portugal has indeed provoked the United States by banning all her shipping from his ports and confiscating some of her vessels), always with the proviso that such an enterprise does not incur the displeasure of the French and Spanish Courts and that they are in a position to support it. [27]

Franklin continued to Aranda:

On the assumption that the two nations be closely united in this common enterprise, and that they both deem it tactically sound to mount an attack on the British Isles in the Caribbean, Congress, in addition to what is set out above, proposes to provide supplies to the value of two million dollars and to furnish six frigates, each of at least twenty-four guns, fully equipped and ready to go into service in the joint fleet, and also to take all other measures at its disposal, as befits a true ally, to ensure the success of the said attack, and to do all this without being motivated by any desire whatever to occupy the said isles in her own name. [28]

The ministers in Spain refused an immediate alliance as proposed by Franklin, but proposed to aid the Americans secretly. Arthur Lee left Paris for Spain in February 1777, returning after being told he would get help directly from Spain or from New Orleans, principally by the Gardoqui banking house, whose principal, Diego de Gardoqui, was a Spanish merchant who was to play a critical diplomatic role.

Gardoqui received from the Spanish Treasury first 70,000 pesos, and then another 50,000 pesos, to be sent to the Americans. Drafts in the amount of 50,000 pesos were also sent to Lee, and Gardoqui himself sent merchandise worth 946,906 reales, including 215 bronze cannon, 30,000 muskets, 30,000 bayonets, 512,314 musket balls, 300,000 pounds of powder, 12,868 grenades, 30,000 uniforms, and 4,000 field tents.

Diplomatic contact between Carlos and the American revolutionaries was ongoing. Juan Miralles was sent by Spain to the North American Congress, and John Jay and his secretary, Carmichael, went to Madrid to petition for continuing financial aid. When Miralles died at the end of 1780, Diego de Gardoqui was nominated to take his place.

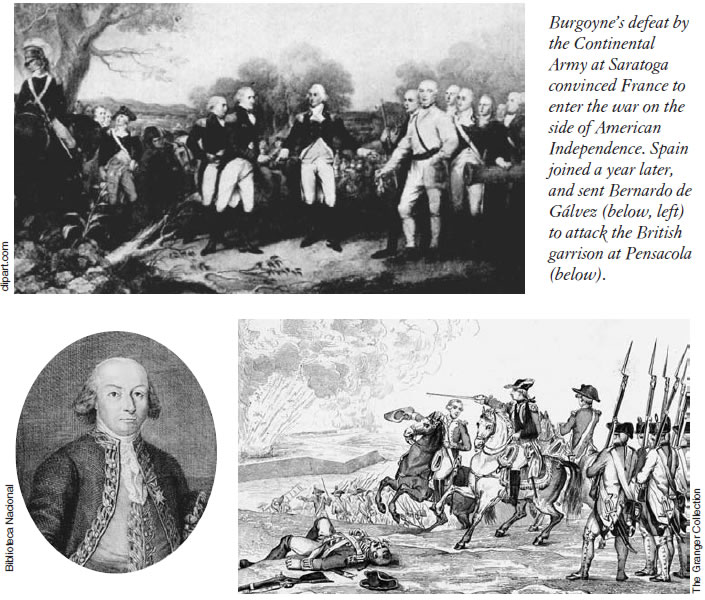

The capitulation of Gen. Burgoyne at Saratoga in October 1777 had a major effect, both on the combatants, and on France and Spain. The American victory at the battle was the result of the supplies in arms, ammunition, uniforms, etc., sent by France and Spain to the newly formed Continental Army. Winning this battle was a turning point, both for the Continental Army and for Britain. The former was remoralized by its victory over the “greatest army” in Europe, while the latter was demoralized by its defeat.

In the case of Carlos III, the victory at Saratoga went a long way towards convincing him that Britain’s days of greatness were at an end. Spain was not yet ready to declare war against Britain, however. Burgoyne’s surrender, on the other hand, did convince the Court of France to declare openly against Britain, and in February 1778, France recognized the independence of Britain’s North American colonies, concluding treaties of alliance and commerce with them. Communication of this to England was met by a declaration of war. France officially entered the war on June 17, 1778.

While secretly supporting the American Revolution, in 1778 Spain offered to intervene, with Carlos III playing the role of mediator between Britain and the colonists. France agreed, and the Spanish embassy bargained with Britain for Gibraltar as the price of mediation. Britain refused, both because it refused to surrender Gibraltar, and because mediation would have given de facto recognition to the independence of the colonies.

When the British frigate Arethusa fired on the French Belle-Poule, Vergennes advised Floridablanca to put the Family Compact into action. Spain addressed a list of grievances to Britain, which were rejected in an answer written by none other than British Empire historian Edward Gibbon.

Spain Declares War on Britain

Spain finally declared war on Britain on June 21, 1779, at the same time recognizing the independence of the thirteen colonies.

Spain then undertook military activity against Britain, both in Europe and in the Americas. At Spain’s insistence, as a condition for entering the war in alliance with France, a plan was launched for a joint French-Spanish invasion of Britain. The initial plan was to capture the Isle of Wight and Portsmouth, thus establishing French- Spanish control over the English Channel, while severely damaging Britain’s shipbuilding capacity, which was centered at Portsmouth. Even though the joint fleet sailed, the invasion, which was scheduled to take place soon after the Spanish declaration of war in the summer of 1779, was called off after a number of delays.

Nonetheless, the deployment of this French-Spanish fleet did have the effect of tying up British forces. The very threat of such an invasion prevented the British from deploying more heavily in the war against the colonies. Spain also decided on a blockade of Gibraltar, which was announced in June 1779. The blockade was ultimately unsuccessful, but again forced the diversion of British forces from North America.

|

The most important Spanish military actions took place in the Americas, however, where José de Gálvez, Minister of the Indies, whose nephew, Bernardo, was Governor of Louisiana, wanted to fight the British. He had been sent to Spanish America by Carlos III in 1765, had therefore supervised the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767, and had thereafter implemented educational reforms to promote economic development. Gálvez reported that, had Carlos not expelled the Jesuits, “America would have been lost” to Spain. [29]

On May 18, 1779, prior to the official declaration of war, the Spanish court sent notification to her colonial officials that war had been declared against Britain. The news reached Havana on July 17, at which point an order, reflecting Benjamin Franklin’s early military proposal to Carlos III, was sent to Bernardo de Gálvez in Louisiana “to drive the British forces out of Pensacola, Mobile, and the other posts they occupy on the Mississippi.” A subsequent royal order was more precise: “The King has determined that the principal object of his forces in America during the war against the English shall be to expel them from the Gulf of Mexico and the banks of the Mississippi, where their establishments are so prejudicial to our commerce, and also to the security of our more valuable possessions.”

Hostilities between Spain and Britain began in 1779, when Roberto de Rivas Betancourt, Governor of Campeche in Mexico, sent two detachments against the British forces in the area. One detachment, under José Rosado, took Cayo Cocina; the other, under Colonel Francisco Piñeiro, destroyed the factories of Rio Hondo, and drove the British out of the Campeche region.

In August 1779, Bernardo de Gálvez mobilized a force of 2,000 men in Louisiana to capture the cities of Manchak, Baton Rouge, and Natchez from the British. The Choctaw Indians, with their 17 chiefs and 480 leading warriors, made a pact with Gálvez, promising 4,000 men. In the opening months of 1780, Gálvez, with 1,200 men, marched on Mobile and besieged it, and in March of the following year, Colonel Dunford surrendered with his garrison.

On March 9, 1782, Gálvez anchored his 74-gun flagship, the San Ramon, in Pensacola Bay. He had 1,315 troops from Cuba. Another 2,253 men came from Mobile and New Orleans. On April 19, another detachment of some 1,300 Spaniards arrived. On May 7, Pensacola surrendered to Gálvez. General Campbell and Admiral Chester were taken prisoner, together with 1,400 soldiers.

Another member of the Gálvez family, Bernardo’s father, Matias Gálvez, President of the Audiencia (High Court) of Guatemala, captured the fortress of San Fernando de Ornoa, held by the British, on Nov. 28, 1779. This led to a general attack on the British settlements on the Gulf of Honduras and the Mosquito Coast. The British temporarily took San Juan de Nicaragua, but Gálvez organized to retake it, making Masaya his headquarters and ordering Tomás López de Corral to keep watch on enemy movements in Costa Rica. López kept watch, and also captured the British settlements of Tortuguero and Bocas de Toro, while early in 1781 Matias Gálvez clinched the campaign with the capture of San Juan de Nicaragua.

On other fronts, Floridablanca was instrumental in procuring the declaration of Armed Neutrality from the Empress of Russia and the formation of the Northern League.

Footnotes:

[26]. Quoted in W. N. Hargreaves-Mawdsley, Spain Under the Bourbons, 1700-1833; A Collection of Documents (London: MacMillan Press, 1973)., pp. 150-51.

[27]. Quoted in Hargreaves-Mawdsley, ibid., p. 156.

[28]. Quoted in ibid., p. 156.

[29]. Quoted in Cynthia Rush, “Real Cultural History of Latin America: Charles III’s Spanish Commonwealth,” 1982 (unpublished).