How Erasmus’s Folly Saved Our Civilization

By Karel Vereycken

April 2013

This article, first published in 2004, appears in the original French, on the culture page of the Soldarité et Progrès organization in France: http://www.solidariteetprogres.org/bibliotheque. It was translated into English by the author with assistance from Richard Sanders.

Erasmus on War

Hans Holbein, Jr. Erasmus (1523). Private collection of Lord Radnor of Longfares, Salisbury. |

“The education of a Christian Prince, Chapter 11: On starting wars

“Although the prince will never make any decision hastily, he will never be more hesitant or more circumspect than in starting war; other actions have different disadvantages, but war always brings about the wreck of everything that is good, and the tide of war overflows with everything that is worst; what is more, there is no evil that persists so stubbornly. War breeds war; from a small war a greater is born, from one, two; a war that begins as a game becomes bloody and serious; the plague of war, breaking out in one place, infects neighbors too and, indeed those far from the scene.

The good prince will never start a war at all unless, after everything else has been tried, it cannot by any means be avoided. If we were all to agree on this, there would hardly be any war among men. In the end, if so pernicious a thing cannot be avoided, the prince’s first concern should be to fight it the least possible harm to his subjects, (…) and to end it as quickly as possible.

The truly Christian prince will first ponder how much difference there is between a man, a creature born to peace and good will, and wild animals and beasts, born to pillage and war, and in addition how much difference there is between a man and a Christian.

(…) Finally, putting aside all emotion, let him apply just a little reason to the problem by counting up the true cost of the war and deciding whether the object he seeks to achieve by it is worth that much, even if he were certain of victory, which does not always favor even the best causes.”

PROLOGUE:

One often characterizes as “a little dark age” the period stretching from the beginning of the religious wars (1511) till the treaty of Westphalia (1648) that organized their ending. While the world plunged into the horrors of useless wars, humanity also discovered Erasmus In Praise of Folly published that same year.

A tragic irony in history, since the very principle of the “advantage of the other," the crucial revolutionary concept employed by Cardinal Mazarin as the keystone for obtaining the success of the peace of Westphalia and alternative that could have avoided these wars, was already embedded in the works of Erasmus.

That notion is also the subject matter of most of the writings of one of Erasmus leading admirers, François Rabelais. For example, Rabelais describes Gargantua’s father offering a personal bronze medal for his son featuring a human body on with two heads turned one towards the other, with four arms, four feet, and two posteriors (taken from Plato’s dialogue The Banquet). Around the figure one can read in classical Greek: “Agape doesn’t look for its own advantage.”

These wars of “sedition," as Erasmus called them, since they were conflicts among Christians, were nothing but the murderous expression of the deliberate intent by the great financial powers running feudalism and imperial Rome (Lombard bankers, the Venice-trained Fugger bankers, and their ilk of Genoa and Venice) to annihilate the Golden Renaissance of the fifteenth century and desperately engaged in brushing aside with the back of their hand the burning demands for political reform that was thrown on the table of humanity.

If mankind did survive this counter Renaissance, illustrated by the stakes of the SpanishInquisition and the casuistic words of the Jesuits at the Council of Trent, it was essentially for the action, the love and the works of a great man, Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536), indefatigable beacon of wisdom for his period and many centuries to come.

At the Council of Trent, his writings were outlawed by the Roman Catholic Church and put on the list of heretical writings (the infamous Index Vaticanus) from 1559 till 1900 (!) Besides many books, annotations, comments, dialogues, Adagia and other writings, Erasmus wrote an average of forty letters every day! While the total number of that correspondence is estimated outnumbering twenty thousand, the study of the surviving three thousand letters make it possible to follow day by day the mind of a man, which in total disregard for his poor health, life, honor, reputation and little fortune, was the daring leader of a bold international resistance.

Behind the nice sounding title of Prince of the Humanists and far different from any form of academic comfort as a member of the Republic of Fine Literature, he travels incessantly all over Europe with crates of books, tirelessly mobilized to unite all men of good will. Luther, with disgust, was the first to call him “Errans Mus” (erring rat).

But from Madrid to Stockholm, from Cambridge to Gdansk; in Leuven (Louvain), in Leipzig, in Strasburg, Antwerp, Rome, London, Basel, everywhere Erasmus builds a coalition around the hope of a better world. Most of his letters were immediately published, his books translated into several languages and his literate correspondents, many of them at the higher power echelons of state responsibilities, informed him in return of anything relevant to the great cause he stood for.

Aware of the responsibility history gave him, he will rise up without compromise (Nulli concede [I don’t flinch], initially a reference to the inexorable character of death itself, will be his device) to bring into light, but with a just word and compassionate spirit, the truth that disturbs many, but increases the love for the public good of all. To safeguard that freedom of speech, indispensable for his universal mission, he declines all offers of earthly power coming from kings, princes, dukes, popes, diets or councils.

Erasmus never tries to be a good catholic, a good protestant or even a good Erasmian. As a Christian he runs away from narrow doctrine and sterile dogma, unwilling to get dragged into partisan quarrels. This exceptional conduct, together with his permanent disgust for the vanity of earthly glory make him a permanent, potent reference to all those that opposed the orgies of greed sweeping the world at that time. Moreover, his agapic love for Christ, humanity and classical literature, will resist the tempest of hate and moral ugliness so characteristic for his times, while his satirical humor, as humanity discovers it in his “In Praise of Folly," will offer finally mankind the opportunity to laugh at its own shortcomings and stupidities, to overcome them and become free at last.

His youth movement? One can see it in the works of three giants of world literature. Each of them, Rabelais in his letter to Erasmus, Cervantes trained by the Erasmian Lopez de Hoyos, and Shakespeare by his acquaintance with the work of Thomas More, all happen to be ripe fruits of his rich inspiration.

Besides inquiring into his political role during the events of the League of Cambrai featuring the mortal conflict against Venice, we will try to circumscribe the key concepts that defined his outlook and teachings.

First, in the tradition of Nicolas of Cusa and John Bessarion, Erasmus wants a simplification of Catholic liturgy to make available to all the philosophy of Christ as formulated by the Gospel and the deeds of the Apostles. Contrary to the scholastics, and similar to Petrarch, he considers that revealed truth, accessible through religious faith, is not incompatible with philosophical wisdom of ancient authors, and Plato in particular, a wisdom that is the fruit of human reason.

Then, armed with this evangelical Christianity, he takes up Plato’s Republic and readapts it for his own times with the aid of his dear friend Thomas More in the form of his Utopia. This vision, free of the pessimism of Machiavelli’ pragmatic humanism and beyond the passive notion of tolerance, since founded on the active concept of the advantage of the other, will be the leading influence on the Politiques (Coligny, Bodin, Sully, etc.) and Henry IV’s Edict of Nantes and the crucial keystone for the success of the peace of Westphalia bringing finally an end to the religious wars.

To fight the pessimism of the scholastics and the Sorbonne, and against what one could call a form of stoic (and later Lutheran) “catharism," Erasmus mobilizes Christian Epicureanism that he takes from the Italian humanist Lorenzo Valla. The development of that notion will bring us to the concept of the pursuit of happiness so unique in the USA’s declaration of independence.

In 1516, Erasmus is convinced that he is at the threshold of gaining a decisive victory in his battle for reform. It is therefore necessary to put some question marks behind the sudden “spontaneous” appearance of Martin Luther in 1517 and the way his radical views were used to polarize the world back into sterile theological disputes that should have belonged to a distant scholastic past. To fight Luther’s extremism, and going beyond Augustine and Valla, Erasmus will defend a human “Free Will” capable of cooperation, if desired, with divine grace. However, his diatribe also hits powerfully the “mendicant tyranny” of the corrupt syndicates of the beggar orders that gave the word “religion” a bad reputation.

Aware of the systemic crisis and the risks of war and the Inquisition, Erasmus turns up the heat on those he loves, to force them to bring about a progressive, reasonable and humanist reform of the church and society. To achieve that aim, and exasperated by the decadence of the humanists of the Italy in which he had put all his hope, he publishes “The Ciceronian," a satirical attack against the blatant paganism that, disguised as cultivated mannerism, had taken over Rome.

Targeted by an incredible witch-hunt organized by Girolamo Aleandro, scion of an old oligarchic family of Venice, Erasmus becomes undesirable in London, slandered in Rome, harassed in Leuven, defamed in Paris, insulted in Madrid and even one of his belittlers spits every morning on his effigy. Politically, he feels obliged to leave Leuven and later Basel where he will return and die, one year after the death of his beloved “twin brother” Thomas More, beheaded by his pupil, a slave of passion, but king of England Henry VIII on June 22, 1535.

While Luther states that “Erasmus should be crushed as a bug” and while Calvin accuses him of impiety, many Protestants and reformers will happily prefer Erasmus generous humanist worldview to the cruel Biblicism of Martin Luther or the catholic theologians of the Council of Trent.

To conclude our article, we will shortly look to one of Erasmus most brilliant followers, the French Erasmian, François Rabelais.

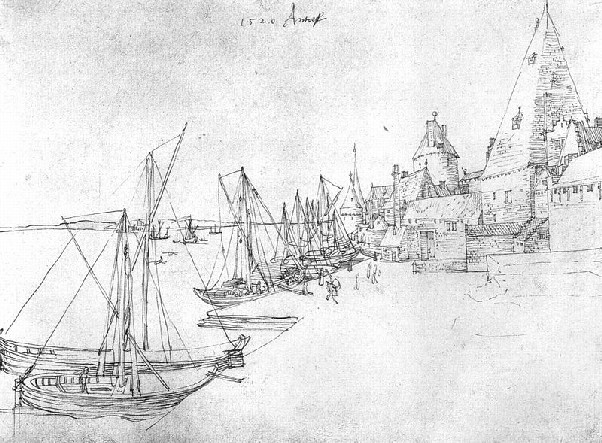

The “fatherland without name” of Erasmus, Antwerp circa 1500

Albrecht Dürer, drawing of the port of Antwerp, 1520. Graphishe Sammlung, Albertina, Vienna |

It is one of these mornings when the Flemish fog throws its misty cloak over the shoulders of the cities of the Low Countries. Avidly peering down, a myriad of seagulls, dressed in Payne’s gray costumes, shriek their mocking chirping. What a crowd in this ocean of grayness!

Stowed on the wharfs of the Schelde, the fishing armada feverishly unloads its freight of baskets overflowing with crabs, shrimps, maatjes herring and kabeljauw. Of course, even the little verdigris seal that came in with the surf, thanks to the rising tide, shares the vain hope that one of these bountiful baskets might fall over board and offer its delicatessen before the coming winter transforms the icy river in a huge skating-rink!

Bordering the seafarer’s church Sint-Walburgis and the Steen (feudal castle), erected six centuries earlier on the wharf of the river, the Oude Vismarkt (old fish market) is now the busiest quarter of Antwerp. In the early fifteen hundreds, this cosmopolitan city breathed as the lungs of the world and its walls embraced close to ninety thousand souls.

Passing the Palingbrug (eel bridge), where there are important remains of the first ramparts, one discovers the impressive Vleeshuis (butchers house), a modern slaughterhouse surmounted with rooms for business dealings. Not far from there, in the newly urbanized area of the Nieuwstad, on the Brouwersvliet (brewers canal), well equipped breweries will soon transform streams of clean water, ingeniously channeled into the city thanks to the grandiose water management projects of Gilbert van Schoonbeke into rivers of beautifully amber-colored beer.

The Antwerp of the Fuggers has outdone the Bruges of the Medici’s as the biggest warehouse in the world. Between the Oosterlingenhuis, once the headquarters of the Hanseatic league and the Beurs [Exchange], you can easily run into a Portuguese, Spanish, Jewish, Levantine, Armenian, English, French, Scandinavian, German or Italian merchant. Silk and spices, brought into Italy from the Far East by the caravan routes, are sold here over the counter or exchanged against the timber of the Baltic or the grains of Poland. Linen and Flemish cloth, English wool, wines of Bordeaux, any product here finds an eager client thanks to the precious metals of the Danube.

Women musicians. |

In Antwerp, as in so many other cities of the Burgundian Low Countries, the elevation of the facades of guildenhuizen (houses of the corporations) on the Grote Markt (central square), is always a breathtaking tourney of architecture. While new types of boats, the Kraken (carracks) are under construction on the wharfs, laborers sculpt in the backrooms of their workshops polychrome altars much wanted in Scandinavia. Based on the blueprints sent by the most prestigious courts of Italy and France, tapestries are patiently being woven. The Ars Nova, started by Jan van Eyck in Bruges in the domain of painting and by Philippe de Vitry in France in music fifty years earlier, blossoms here. Choruses perform the new polyphonic music, carillons impose their melodies and Orlando di Lasso composes for harpsichord. Paintings make merchants dream of vast mountains and simple citizens have their portraits done. In the shadow of the cathedral, finished by architect Keldermans, and in the Begijnhoven [cloisters] proud women recite the pious poems of Hadewijch and Beatrijs while agile fingers manufacture beautiful lace, often harmonic with waterfalls of sculpted stone ornamentation of Skaldic gothic that crowns the pinnacles of the City halls, of particular residences or the roofs of the bell towers of innumerable churches.

In the large patrician estates build in stone, the Rederijkers (chambers of rhetoric) prepare satirical sketches, memorize religious stories and decorate allegorical floats (such as the Haywagon) for the Ommeganck (procession) of the Saint John’s harvest feast.

An extraordinary encounter

To imagine the breeding-ground of ideas and creativity that represent the century that crystallizes in Antwerp, one can easily imagine some unusual meetings in one of these minuscule houses or taverns of the Vlaaikensgang ( little pie ally) on the border of one of the Vlieten (canals) that irrigate the city.

Usually, Thomas More (1478-1535) and Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) met here at the house of Pieter Gillis (Aegidius) (1486-1533), the secretary of the city who owned a large mansion called Den Spiegel [the Mirror] on the Eiermarkt (egg market). But today they decided to meet at the house of the painter Quinten Metsys (1465-1530), in his house Sint Quinten, decorated with Italian style fresco’s in the Schuttershofstraat (crossbowman street) and who for that occasion invited his friend and colleague Gérard David (1460-1523). Metsys shows them the sketches he made in Italy after the “Saint Anne and the virgin” of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519).

Albrecht Dürer: charcoal portrait drawing of Erasmus, 1520, Louvre, Paris. |

But lo and behold! Today is the day of arrival of Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528)! Erasmus impatiently looks forward to having his portrait done by the great master of Nuremberg of which he admires the engravings: “Dürer (…) knows to render in a monochromatic way, i.e. with black traits – what can he not render! Shadows, light, splendor, heights and depths, and… (Perspective). Even better, he paints that what is impossible to paint: fire, thunder, lightening and even as one says, the clouds on the wall, all the sentiments, and finally the whole human soul reflected in the disposition of the body, and nearly language itself.”

While waiting, Erasmus and More crack some jokes and imagine the beginning of the Utopia where More counts how he meets Gilles by chance at the end of a mass in Onze Lieve Vrouwe (Our Lady’s) Cathedral of Antwerp in the presence of a traveler, the famous Raphaël Hythlodeus who tells him what he saw on the island of Utopia, a humanist republic that he visited in the newly (re)discovered America. Another friend of Erasmus, Erasmus Schetz (1480-1550), industrialist and accomplished Latinist, offers them the precious information he collected from the new world coming from the network of Portuguese merchants he runs in Brazil. Also Martin Behaim (1459-1509), the pupil of the brilliant cartographer of Nuremberg Johan Müller (Regiomontanus) (1436-1476) whose library Dürer bought up, builds some of his earliest globes in Antwerp before installing in Portugal where it is thought he met Columbus.

Dürer resides for over a year in Antwerp from 1520 to 1521 where he attends the wedding of Joachim Patinier (1480-1524) where he meets Jan Provost (1465-1529), Jan Gossaert (1462-1533) and Bernard van Orley (1491-1542). In the same city, he makes a portrait sketch of Lucas van Leyden (1489-1533), and the famous portrait of a 93 year old bearded old man who became the model for his St. Jerome.

At a stone’s throw distance, in Mechelen, Dürer visits another admirer, Margaret of Austria (1580-1530), the aunt of Charles V, twice regent of the Burgundian Low Countries, who sometimes heeded Erasmus’s advice. Being her guest, Dürer admires an incredible painting in her collection, the Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife by Jan van Eyck. Margaret just decided to grant a pension to the Venetian painter Jacopo Barbari (1440-1515), a political refuge in Mechelen and author of the portrait of Luca Pacioli (1445-1514), the Franciscan monk who initiated Leonardo into Latin and Euclid, and author of the Divine Proportion. Dürer probably also visits the beautiful residence of Jérôme de Busleyden (1470-1517), financial backer of Erasmus’s Collegium Trilingue (Three language college) set up in Leuven in 1517 and friend of Cuthbert Tunstall (1475-1559), the young bishop that introduced More to Busleyden.

Back in Antwerp, Dürer draws the portrait of Sebastian Brant (1457-1521) of Strasburg which published in 1494 The Ship of Fools in Basel.

The painter Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) who painted that interesting subject, had quite some fun with Erasmus In Praise of Folly of 1511, illustrated by the young Hans Holbein (1497-1543), and rushes to Antwerp to buy a copy of the Utopia freshly printed in Leuven in 1516 by Gilles friend, Dirk Martens (1486-1534).

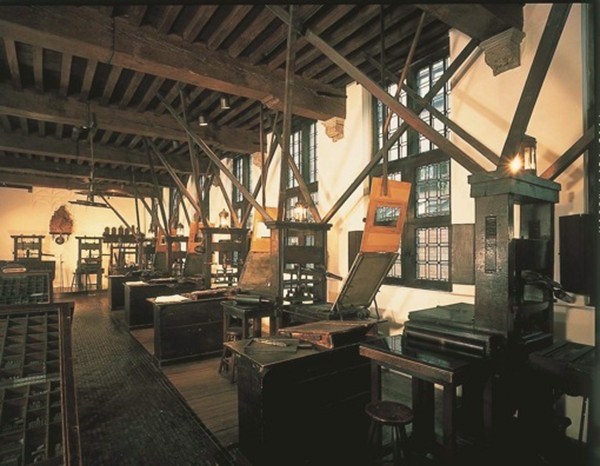

The print shop of Christophe Plantin, one of 56 in Antwerp, used 22 presses and employed 160 workers. |

Gemma Frisius |

Shortly afterwards, when the Spanish Inquisition starts to thicken the mist with the smoke of the stakes, the printer Christophe Plantin (1514-1589) sets up a secret meeting for the members of the humanist group of Hendrik Niclaes (1502-1580), the Huis van Liefde (Scola Caritatis).

Gemma Frisius (1508-1555) discusses with his pupil Gerhard Kremer (Mercator) (1512-1594) and Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) explains the latest discoveries of explorers crisscrossing the globe to the young Pieter Bruegel (1525-1570) who prepares his series of engravings on the theme of The seven sins and the seven virtues for the printing shop In de Vier Winden (In the four winds) of Jerome Cock (1510-1570). Bruegel comments on his readings of François Rabelais (1494-1553) whose book he bought in Lyons on the way back from his trip to Italy. In the Vier Winden (four winds) there is also an engraver and philosopher at work, Dirk Coornhert (1522-1590), trained by a young secretary of Erasmus Quirin Talesius (1505-1575) and future key advisor to the organizer of the victory of the revolt of the Netherlands, William the Silent (1533-1584).

Economic expansion and political emancipation

The rich urban culture we just discussed would never have seen the light of day in the Burgundian Low Countries without a vast agricultural revolution on the march since the end of the tenth century. The geography that draws the lines of the Golden delta formed by the Rhine, the Meuse and the Schelde offers in that region an exceptional natural infrastructure, enriched by man's handiwork with a labyrinth of waterways and an impressive shield of sea dikes operational as early as 1300 A.D. and more and more surmounted by thousands of wind and water mills.

The polderization (reclaiming land from the sea) and intensive farming methods made it possible to increase agricultural productivity when it was declining elsewhere. Economists estimate that where in the rest of Europe it took four peasants to feed one person living in the city, only two were required in the Low Countries. If we take an urban community of 10.000 people as a unit, we find present day Belgium at the top of the scale of urbanization in 1550 (with 21 percent), followed by the Netherlands (15,8 percent) and northern Italy (15,1 percent). If one lowers the criteria to 5.000, Flanders reaches 36 percent around 1500, and the region between the Meuse River and the Zuiderzee (Brabant and Holland) reaches 54 percent. Together with Italy, Erasmus fatherland was undoubtedly one of the most densely populated regions of Europe.

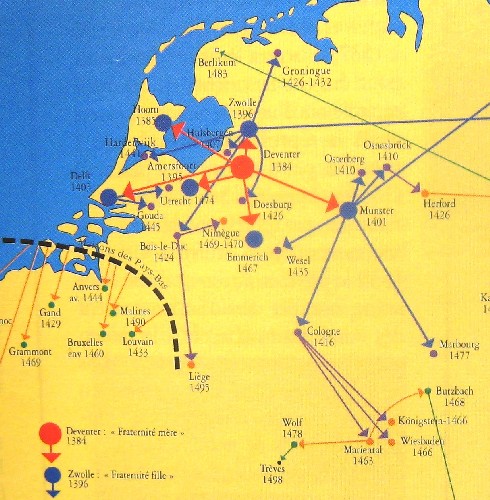

Map of the Burgundian Low Countries. |

From 1384 on, the Dukes of Burgundy had tried to unify the large territories going from Friesland to the old Roman road that went from Boulogne to Cologne. Although the Duke governed the country with the members of the Order of the Golden Fleece, the government largely integrated pre-existent forms of self rule into its own power structure. Historically, the pioneering war against the sea, and the conquest of useful farmland had resulted in a decisive setback for political feudalism, to wit, economic development that led to a new political emancipation of the citizens. Communal committees, in charge of the financing and maintenance of the dikes and polders and water management in general, discovered their collective capacities to handle their own interests. To facilitate the decision process, the communes were structured into “Staten” (states), although ad hoc meetings could be organized by specific committees, for example those regrouping the cities involved in the herring fishery.

Unlike England or France, where parliaments would meet but very rarely and mostly to settle fiscal and financial matters, the registers of the Burgundian Low Countries indicate a far different situation. For example, in Flanders, delegations met 4055 times between 1386 and 1506, or an average of 34 times a year in order to debate social matters and infrastructure programs. For the same period, in England there were but 73 meetings between 1384 and 1510, i.e. less than one session a year!

Palace of Margareta of Austria in Mechelen |

With the accession of Charles V, son of Philippe the Fair of Burgundy and Jeanne de Castile (“the mad”) born in Ghent, the country falls in the hands of Habsburg. But, since Charles is too young to rule, and often far from home, the country will be governed by the Flemish regents, Margaret of Austria and Mary of Hungary. They will consolidate the central government by the institution of a State Council, a Privy Council (justice), and a Finance Council. In 1548, Charles V creates the Circle of Burgundy regrouping the ten southern provinces with the seven northern one’s which had until then, been outside the empire. He also takes the necessary steps to enable one single king to inherit the entire Generality of the seventeen provinces; a country the Habsburgs gave the pejorative name of the “low countries.” Charles’ son, Philip II, born in Spain, once admitted that he would “prefer to rule over a desert than over these populous cities”; Schiller’s “Don Carlos” tells us the rest of the tragedy.

This gives us a better understanding of the country that Rabelais is thinking of when he writes to Erasmus, “You that are the father of your fatherland and its glory.” That was not merely the fatherland of classical literature! The religious wars were nothing but a perfect pretext to crush the community of principle emerging between newly born nation-states such as France of Louis XI and Jacques Coeur, the England of Henry VII and Thomas More, and the Burgundian Low Countries, the fatherland of Erasmus of which the oligarchs even stole the name.

The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life

Thomas a Kempis |

One rightly underlines the decisive influence on Erasmus of the revolutionary spirit of the Modern Devotion radiated through the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, or Hieronymites, a secular teaching order engaged in the transcription and translation of manuscripts, ultimately regrouped as the Order of Canons Regular of Saint Augustine of the Congregation of Windesheim (Fig. 7).

The spirit of this current is most clearly expressed in the book by Thomas van Kempen (a Kempis) (1380-1471), The Imitation of Christ. The author emphasizes that every human being should follow the sublime example of the Christ in the passion, as exposed by the Gospel, a worldview Erasmus made his own.

In 1475, Erasmus' father, who had apparently heard presentations by some of the famous humanists in Italy and become acquainted with classical Greek, sent his nine years old son to the famous chapter of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, Saint Lebuinius, a school founded personally by an exceptional genius and former pupil of the Brethren, Nicolas of Cusa (1401-1464).

Rodolphe Agricola |

The expansion of the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life from Deventer at the end of the 14th century. |

The school was directed at that time by Alexander Hegius (1433-1498), pupil of the famous Rodolphe Agricola (Huisman) (1442-1485), follower of Cusa and enthusiastic defender of the Italian renaissance and classical literature, and a teacher Erasmus would call a “divine intellect.” At the age of 24, Agricola makes a tour of Italy to give organ concerts and meets Ercole d’Este I (1431-1505) ruler of the court of Ferrara. At the University of Pavia he also discovers the horrors of Aristotelian scholasticism. When teaching in Deventer, Agricola would start a class by saying: “Do not trust anything you have learned until this day. Reject everything! Start from the standpoint that you have to unlearn everything except what you can re-discover based on your own authority or on decrees by superior authors.”

Unfortunately, both of Erasmus’ parents die from the plague when he is young, and he and his brother are placed in a school in ‘s Hertogenbosch. According to Erasmus, the sole aim of this Domus Pauperum, orphanage for the children of the poor run by the Brethren, was to break their students' talents and gifts, using physical violence, reprimands and harshness, to destroy their desire for learning and drive them into a monastery.

Geert Groote |

This is completely unlike the authentic, “mystical” and humanist founders of the early period such as Jan van Ruysbroek (1295-1381) and Geert Groote (1340-1384) or Heymeric van Kempen (da Campo) (1395-1460) (influence on Cusa); in the case of 's Hertogenbosch, the “normalization” of the Brethren with Rome seems to have introduced corruption. Things got so bad, that Agricola and Wessel Gansfoort (1420-1489), prominent leaders of the Brethren, decided to open up their own erudite circle at the Cistercian abbey of Adwerth in Friesland, for the simple reason that there they were allowed access to a library containing abundant humanist literature.

Erasmus, pressured to follow the example of his brother who became a monk in Steyn, is ordained a priest in 1492 where he has books at his disposal. Soon he expresses his desire for freedom by going into politics as the Secretary of the Bishop of Kamerijk (Cambrai), who had recently been nominated Chancellor of the powerful Order of the Golden Fleece.

Erasmus continued friendship with some of the people at Steyn, but never again would anyone be able to convince him that faith was opposed to education, that faith could be genuine and in accordance with the Gospel and yet not oriented towards bringing mankind to act for the good of all mankind.

The Brethren of the Common Life of Magdeburg will also bring forth a far different celebrity: Martin Luther (1483-1546). His father, like Calvin’s father, predestined him for a career as a lawmaker. But in 1505, Luther is nearly killed by lightning during a thunder storm; to find salvation, Luther takes the inverse road of Erasmus and decides to become a monk at the Augustinian hermitage.

Erasmus’ ideals

Erasmus' discovery of the cruel contrast between the moral beauty of the message of the Gospel and the hypocrisy of religious practice, together with his discovery of classical literature, will nourish a double purpose in the heart of Erasmus.

First, he is convinced that the time is ripe for a total reform of the anti-Christian scandalous practice and the oligarchical spirit that took over the Roman Catholic Church. Since the Councils of Constanz (1414), Basel (1431) and Ferrara-Florence (1437), all the great ecumenical councils had tried to face three fundamental problems:

1) The unity of religious doctrine between East and West;

2) The political unity to defend Christendom against the Turks;

3) The reform of internal structures.

It was obvious that as long as the first two points were not really settled, any debate about the third question was idle talk and taboo, as the unfortunate Jan Hus experienced when arrested and burned as a heretic at the Council of Basel on July 6, 1415.

For Erasmus, the problem was not the institution of the Church as such, but the oligarchical forces that dominated it, more and more. The bankers of Sienna and Venice who managed the fortunes of the cardinals and the bishops, the superstitious adoration of relics, the practice of simony, or the monastic orders, feudal empires possessing land, property that ruled over soul and men as over human cattle.

To turn that situation around, Erasmus launched a vast educational movement that he desired protected by a strong pope, capable of resisting the religious orders and financial powers. That is the explicit program of the Enchiridion Militis Christiani (Handbook for the Militant Christian) and the implicit demand of the Moriae Encomium (In Praise of Folly).

As Lorenzo Valla (1403-1457) or as Jacques Lefèvre d’Etaples (1450-1537) formulated it in their own manner, Erasmus wants to take the Scriptures at their origin, i.e. to compare the original texts in Greek, Hebrew and Latin, very often completely ignored if not entirely corrupted by over a thousand years of copying and scholastic commentaries.

To achieve this Herculean objective, Erasmus plans to found a tri-lingual college bringing together the wisest and most competent men, as far removed as possible from commonplace polemics and scholarly careers. Thanks to the patronage of his friend Jérôme de Busleyden, the project will start effectively in 1517 in Leuven, but will quickly be targeted and sabotaged by the theologians for threatening their pseudo religious superstition.

Then, of course, the optimistic message of evangelical Christianity by its very nature calls for the defense of the General Welfare (Res publica Christi, or the Christian Commonwealth) and for the indispensable political reforms required to make that into a reality. That is the subject-matter developed by Erasmus and Thomas More in the Utopia. That utopia is not utopian at all, if a classical education, starting as early as at the age of three, is guaranteed for each. This purpose is shared by Erasmus Thomas More and Juan Luis Vives (1492-1540), and it is the purpose of Erasmus’ Adagia, which contains over four thousand densely elaborated aphorisms and proverbs, in a rich and beautiful language, a magnificent tool to uplift his fellow men.

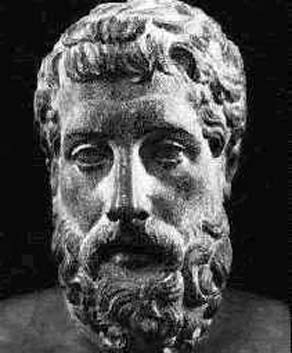

At the same time, taking up the lonely fight of Petrarch, Erasmus wants to reconcile this “philosophy of Christ," transmitted by St. Jerome(317-419) and Origen (185-251), and those (and uniquely those) who in antiquity “by the light of nature got a glimpse of what is given to us by the Gospel,," specifically, Plato.

He says: “That philosophy (of the Christ) is really more in our sensibility than in syllogisms, more in life than in discussion; it is more an intuition than an erudition, an inspiration than a reason; it is the fate of a small number of erudite beings, but I think it is not tolerable for anyone to not be a Christian; no one has the right to not be devout, and I would add with hubris that it is not permitted for anyone not to be a theologian. What is most in conformity with nature penetrates more easily into the souls. So, what is this philosophy of Christ, this philosophy he calls being born again [John 3, 3][re-naissance], but the return to a well ordered nature? And although no one transmitted these truths more fully than Christ, yet one can find in the works of the gentiles several things in agreement with this doctrine. Was there ever a so vile philosophical theory that dared to teach that money makes man happy…?”

With Valla, whose “Elegantia” he read, and his friend Juan Luis Vives, he thinks it is quite urgent to reshape a social language, in particular a literate form of Latin and a pedagogical approach that reflects, by its beauty and musicality, and its compassion, all the nobility of its content. Hence, the crafting of the 1497 Familiarium Colloquiorum Formulae (Formulas for Friendly Conversation).

Lorenzo Valla

Lorenzo Valla |

Leibniz states without any hesitation that the two greatest minds of the Middle Ages were Nicolas of Cusa and Lorenzo Valla. The young Erasmus recognizes in the latter the representative of the ideal Italy he admires.

Born in a wealthy Roman family, Valla had the benefit of particular teachers. One of his preceptors was the Greek scholar and former papal secretary of Eugene IV and Martin V, Giovanni Aurispa (1369-1459), as well as Leonardo Bruni (1370-1444), a student of Coluccio Salutati (1331-1406) . In the same vein as Petrarch, these humanist intellectuals saw the alliance between sophist philosophers (Aristotle in particular) and scholastic theologians as the cement of a feudal anti-Christian Dark Age. At the University of Padua, Valla stages a riot against the dominant current of Averroism.

Averroes |

Ibn Rushd (Averroes, 1126-1198) is often considered, and especially by those that espouse the French Enlightenment, as the harbinger of the spirit of modernism (since he wrote about wine and sex…) Reality is far different, starting from the Arab translations of Aristotle, Averroes forged a philosophy ideal for maintaining the feudal order. According to him, one has to accept the double character of truth. On the one side, with the aid of signs and symbols, religion is able to communicate a form of truth to the vast multitude of illiterates. On the other side, a tiny elite can penetrate truth itself, which is entirely philosophical. What is true in theology can be entirely false in philosophy, but in the last instance, it is reason alone that decides without the need of any transcendence. Averroes even elaborates a treaty on the harmony between philosophy and religion founded on that rotten basis. But of course, teaching philosophy to all would be a disaster, since religion alone can bring a (symbolic) knowledge of the truth to the many. Today, one would accuse him rightly of being a follower of the Leo Strauss’ Kingdom of Lies.

Averroism was the instrumental ideology chosen and promoted tenaciously by the Venetian oligarchy to dominate the world as the modern Aristotelianism

Petrarch |

A century earlier, Petrarch (Francesco Petrarca, 1304-1374), when staying in Venice, denounced the intellectual assaults of four Averroist oligarchs (three of these Venetians being Dandolo, Contarini and Talento) that tried to recruit him to their conspiracy and who “according to the habits of modern philosophers, think to have done nothing worth anything, if they didn’t bark against the Christ and his supernatural doctrine.”

Petrarch’s book De sui ipsius et multorum ignorantia (On my own ignorance and that of many others) elaborates that polemic.

“Had they not feared the punishment of Men even more than that of God, they would have dared, says Petrarch, to attack not only the creation of the world according to the [Timaeus], but also Genesis according to Moses, and the Catholic faith and the sacred dogma of Christ. When this fear does not keep them within bounds, , and when they can speak without constraint, they combat the truth directly; in their secret meetings, they laugh at Christ and adore Aristotle. When they debate in public, they protest that they make abstraction of faith, i.e. that they look for truth by rejecting the truth, and desire the light by turning their back to the sun. But in secret, there is no blasphemy, sophism, jest or sarcasm that doesn’t come out of their mouth, to the great applause of their auditors. And how they treat us as illiterates, when they call Christ, our master, an idiot? They go about inflated with their sophisms, self-satisfied and with the firm conviction that they can debate everything without learning anything.”

After publishing this book, Petrarch had to leave Venice.

Against the suffocating asceticism that makes hope sterile and reduces human creativity to nothing, Valla used Epicurus in his writing De Vere Bono (on the True Good), written in Pavia. It is a dialogue where a stoic (Bruni) states that reason alone is the source of virtue. The second speaker (Beccadelli) is an epicurean who states that true happiness comes not from virtue, but from pleasure. What does that mean?

Epicurus |

Epicurus (IVth century BC) specifies that “When we affirm that pleasure is our ultimate aim, we do not mean the pleasures of the debauched or those pleasures belonging to earthly enjoyments, as people ignorant of our doctrine or who disagree or misinterpret it say. The pleasure that we have in mind, is the absence of corporeal sufferings and the trouble of the soul.”

“It is not drinking or continuous orgies, the pleasure of young boys and girls fish and other good food offered by a luxurious table that engender a happy life, but vigilant reason, that carefully seeks out the reasons for a choice to be made and what must be avoided, and rejects vain opinions, that brings great trouble to the soul.”

“In all this, it is wisdom that is the greatest of all goods. That is why wisdom is even more precious than philosophy, because it is the source of all virtues, since it teaches us that we cannot be happy without being wise, nor wise, honest and just without being happy. Virtues, indeed, are one with a happy life, and a happy life is inseparable from them.”

For the Epicurean, says Valla, the heroic deeds that are invoked by the stoics (suicide of Lucretia, etc.) do not find their origin in the desire to be virtuous, but in the search for a pleasure beyond any mere earthly pleasure of the body. Hence, in his dialogue, the last speaker (Cosimo de Medici's librarian and collector of manuscripts, Niccoli) defends the Christian vision that goes way beyond the Epicureans and mocks his predecessors for being unable to recognize that true happiness resides in the faculty of being in agreement with God, while he fully endorses the Epicurean critique of the Stoics. According to Valla and Erasmus, the very idea that a philosophy per se can teach virtue without the love of God and mankind, is a fraud. One does not act for the good because it is virtuous, but because it pleases God, humanity and ourselves. Erasmus elaborates that concept in one of his Colloquia “The Epicurean." The declaration of Independence of the United States, through the influence of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), who starting from Valla and Erasmus, explicitly integrates that notion in the idea of the defense of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” (the good being consubstantial with happiness in Leibniz's best of all possible worlds ).

Erasmus joins Valla when Valla gets angry at the “philosophy” of Averroes and his ilk. One has to realize that in Erasmus’s times there still existed the fight between the “Ancient” (Thomists and Scotists) and the “Modern” (Ockham and Buridan) and to clearly show his distance of the scholastic schools he takes up the concept of “philosophy of the Christ” employed by Agricola, indicating a philosophy he sees expressed by Saint Socrates as he calls him in the Colloquium The religious banquet.

Christian polemist and consequently violently anti-Aristotelian, Valla is obliged to go from city to city and after a while becomes in 1433 the secretary of Alfonso of Aragon (1396-1458) in Naples. There, he elaborates a treatise On the free will and in 1440, on the basis of rigorous philological criteria, he refutes the authenticity of the Donation of Constantine already exposed by Nicolas of Cusa in his Concordantia Cattolica. This text, a forgery, gave extravagant quasi-imperial privileges to the Pope and guaranteed the total control of the great Roman families over the college in charge of the papal election.

Nicolas of Cusa |

When the humanist pope Nicolas V (Tommaso Parentucelli, 1307-1455) becomes pope in 1447, Nicolas of Cusa and the Greek cardinal John Bessarion (1403-1472) call the painters Fra Angelico (1400-1455) and Piero della Francesca (1415-1492) to come to the Roman Curia, and they put Lorenza Valla, who became scriptor, in charge of translating the Greek historians Herodotus and Thucydides.

In his Repastinatio Dialecticae et Philosophiae (The Uprooting of Dialectic and Philosophy), Valla states he wants to refute “Aristotle and the Aristotelians, in order to preserve the theologians of our time from error, and bring them back to true theology.”

For Valla, contrary to the logic of Aristotle, the seat of the soul is neither the intellect nor the will, but the heart (and Rabelais will say, the blood). The separation between intellect and will is artificial, for it is “one soul that understands and remembers inquires and judges, loves and hates.” So too “love [caritas or agape] is the only virtue, for it is love that makes us good”; and fortitude is the name of love “when it is called into strife,” as with the apostles “who from cowards became the bravest of men when they received the Holy Spirit…”

Erasmus and More together published the works of Lucian of Samosata (125-192). Perhaps not the most creative philosopher, Lucian is an incomparable satirist who said: “I am a man who hates the boastful and the quacks, who dislikes lies and big talk, and profoundly despises rascals (…)Yes, I love that which is truthful, the beautiful, the simple, in one word, what merits to be loved. Nevertheless, I have to admit that there are few people to whom this art can be applied.”

Hence the inspiration of More and Erasmus will be the Gospel, together with Plato’s dialogues, the wit of Lucian and the Christian Epicureanism of Valla.

In praise of Folly

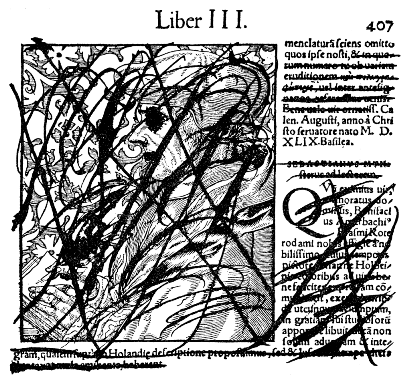

Hans Holbein the younger, page of "In Praise of Folly", fol. B, 40, 1515, Cabinet des Estampes, Basel. |

And since we’re talking about having fun, why not start with the Moriae encomium (In Praise of Folly, with a pun on More’s name, which means folly in Greek)? Written in a couple of days in the residence of Thomas More at Bucklersbury close to London, the work expresses the deep shock Erasmus experienced when discovering the pitiful state in which he finds his Church and his Italy, when he travels beyond the Alps in 1506.

We better grasp what can have guided the hand of the author when we read his work in light of what we just discussed about Valla: to educate an emotion, even when slightly crazy, that emotion has to be allowed to manifest itself! “Stultitia," (the Latin name for Folly) the personification of Folly that oscillates permanently between apparent madness=real wisdom and apparent wisdom=real madness, speaks out and firmly claims her paternity and authorship of everything:

“No society, no life in common could be pleasant or tolerable without folly; there could be no right understanding between prince and people, the lord and his servant, teacher and student, servant and lady, friend and friend, wife and husband, if both parties did not consent to deceive, flatter, wisely pretend to ignore, and then to once again smear the honey around their mouths folly.”

Hence, for Erasmus, there is in the world much more emotion (folly) than reason; yet what keeps the world ticking, the source of life, derives from that folly (wisdom). What is love, if not this? Why would one get married, he or she is following some kind of aberration that is blind to the inconveniencies? All enjoyments and pleasures are nothing but the condiments of folly. What is crazier than procreation? “Why do we kiss and mollycoddle little children, if it were not they are still deliciously foolish? Isn’t it that what gives so much charm to youth?” But folly has a sister that carries the name of self-love, another indispensable ingredient for happiness.

Once he convinces us of that great human truth denied to mankind by scholasticism, Erasmus develops the second theme, discreetly present from the beginning, that (“money” is Folly's father, and it is money who leads the world…) - which takes us by surprise. Here is a magnificent transition from compassion for the folly of the weak to the satirical denunciation of the folly of the strong. From the “soft” folly of the weak, of women and children, of men who through sin have abandoned reason, Erasmus transitions to mobilize all his irony and wit to lambaste the “hard” criminal madness of the powerful, of the “folly-sophers," merchants, bankers, princes, kings, popes, theologians and monks:

“The happiest ones, (…) are those who profess to be members of the religious orders and [monks] (solitary), two very wrongful designations, since most of them are far removed from religion and so much in the street that you can run into them anywhere. I don’t see what misery could go beyond theirs if I (Folly) didn’t intervene to save them in many ways.. Everybody abhors them even to such an extent that it is considered bad luck to have them cross your way; although that doesn’t prevent them from having a grandiose and flattering opinion about themselves. In their eyes, the perfection of piety is to have learned nothing, not even to read. Then, when in church they bawl their psalms which they know by heart without grasping their content, they believe they tickle the ears of the Saints with exquisite delight. Among them, some make their grime and beggaring pay, and they moo noisily at the door for some bread , [there is no tavern, no carriage, no boat where they don’t provoke uproar], of course at the expense of other beggars. And it is in this way, that these exquisite persons, with their filth, their ignorance, their rusticity, their impudence, would pretend to bring the apostles alive for us."

“What more pleasant, than to see them do everything according to rules, according to some kind of mathematical tables whose violation is sacrilege: so many knots on the shoe; this color for that piece of clothing; that diversity among them; such and such a texture and the length of the belt just so, , a proper looking cap, so many fingers wide for the hair, so many hours for sleep. Who does not see the inequality of such equality between so many different bodies and spirits...?”

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Blind Leading the Blind. 1568, Museum of Naples. |

Here we cannot but think about Pieter Bruegel’s painting The blind leading the blind. Scientists recently succeeded in identifying with precision the four different types of blindness that struck the four representatives of different beggar orders! What happens to them in the world? In the ditch!

After this critique, Erasmus forewarns against the cynical “peeping Tom” mentality and the impotent comfort of misanthropy, stating that those who think all this is too ridiculous for consideration, must consider which is wiser: to reconcile yourself to the folly of life (by finding the force to love and to act), or to look for a tree to hang yourself!

The Church of the future

As a counterpoint to this satire, let us imagine this “Church of the Future” that the humanists dreamed about. One finds it powerfully evoked in Chapter 52 of François Rabelais’ Gargantua. In the story, Gargantua offers to build a walled cloister for a monk who distinguished himself by courageously defending the population against the soldiers of Pichrocole (Charles V). The monk answers that “where there is wall before and behind, there is gossip, envy and silent conspiracy."

As an alternative they build the “Abbey of Thelem,"," a hexagonal building with six floors, as good as the magnificent Renaissance castle of the Loire. There, “from the Artice till the Cryere tower were beautiful and large libraries, in Greek, in Latin, in Hebrew, French, Tuscan and Spanish, spread over the different floors according to language,” a very clear reference to Erasmus project for the Collegium Trilingue. [Thelem means desire in Greek, a probable pun on Erasmus' first name "(be)Geert" (NL) or "desired"].

In stead of being a collector of all the scum of the earth, as it unfortunately often happened to be the case for most monasteries, the abbey only accepted beautiful and well-formed individuals “well-formed and of a goodly nature,"," all richly clothed with the most beautiful clothes possible !

In an ironical satire against the self imposed suffering through vespers and other matins, Gargantua claimed that the most efficient way to waste time was “to rule one’ self according to the sound of a bell, rather than dictated by common sense and reason."

Even better, the functioning of the abbey was “not decided by laws, statutes or rules, but according to their desires and free will," a theme largely developed by Erasmus as we will see. Their only rule was “Do the desirable” (often wrongly translated as [do what you want], which eliminates the deliberate ambiguity between the sovereign will and God’s design) “because free people, well born, well educated, conducting a dialogue with good company, have by nature an instinct and desire, that pushes them towards virtuous acts and removes vices, (a quality) which they called honor."

The philosophical optimism expressed by the confidence that man possesses a natural impetus towards the good and increasing self-perfection will remain the dividing line between Erasmus and Rabelais on the one side, and both the Catholic theologians and the followers of Luther and Calvin on the other.

Rabelais’ Gargantua concludes with a prophesy that underscores the fact he clearly was aware that this philosophical revolution would shake up society to such a point that even the most powerful oligarchs would be unable to suppress it, since even “the fierce son will not hesitate to revolt against his own father; And even the Great (rulers), of noble origin, will be assaulted by their subjects…”

Also, once man returned to real love for the teachings of Christ and Humanity, the other problems of the world become so much easier to solve.

The Utopian Republic

Thomas More |

Janus Lascaris |

The work Utopia (land of nowhere) that More started writing as early as 1509 as a diptych for the Praise of Folly, and that Erasmus pressed him to terminate, is above all a satire. In 1516, while Froben published Erasmus’s Institutio Principes Christiani (Education of a Christian Prince), Erasmus completed More’s “Utopia” and saw it through the presses of Dirk Martens in Leuven.

Behind the tale counted by the fictitious Portuguese sea captain Raphael Hythlodeus “who masters Latin quite well and speaks Greek perfectly," Thomas More sketches the project for a real republic, and elaborates an action program for nearly every social and economic problem of the day (security, crime, law, marriage, education, health, retirement, but also currency, monopoly, land reform, tax policy, etc.).

Hythlodeus describes a well organized society: the Utopians possess ships with a flat keel and “sails made of sewed papyrus”; for its people “love to be informed on what is going on in the world," and are believed to be from “Greek origin," since they have (the Greek scholar) Lascaris as their sole grammarian.

At one point it is said: “Oh! If I would propose what Plato proposed in his Republic and what the Utopians put into practice in theirs, those principles, while they certainly are superior to ours,, could surprise us, since here at home, everybody possesses his goods while there, everything is held in common."

That satirical comment has gained all the furious attacks of the world’s anti-communists which saw in More and Erasmus the predecessors of Marx, especially when More attacks the deregulation of the markets:

“Your sheep, I said. Normally so soft, so easy to nourish with very little effort, have become, one told me, so voracious, so ferocious, that they even devour men, that they ravage and depopulate the fields, the farms and the villages. In effect, in every region where one finds the finest wool, and by consequence the most expensive, the noble and the wealthy, not to say some abbots (…), there is no room for cultivating food, the farms and villages are destroyed, ,the pastures are enclosed, and nothing is left but the church transformed into a sheepfold…”

Today, More would be considered an early anti-globalization activist. As far as Plato from any form of Marxism, More argues for the abolishment of private monopolies and demands tariffs and trade regulations in service of the general interest, anticipating the altruistic protectionism of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Friedrich List and Alexander Hamilton.

Even more comical are the passages where he mocks usury and the frantic drive to possess precious metals, a practice at the source of the worst crimes committed against the populations of the Old but especially the New World: “And who doesn’t see that it (the value of gold) is inferior to the value of iron without which no mortal could live (…), while on the contrary nature has not given gold or silver any property that is of value to us, if it were not for the folly of men to put a price on something that is rare? Nature (…), puts at our immediate disposal the best she has, such as air, water, and land; while she keeps us far away from things that are vain and useless.”

In Utopia, “They have imagined a means to deal with this inconvenient situation. (…) While they eat and drink using earthenware crockery of elegant form but without any value, they manufacture in gold or silver, for private houses and common places vessels designed for the most improper uses. They also use as chains and heavy weights to bind their slaves. Whoever has been dishonored by committing a grave fault carries golden earrings, a golden necklace or a golden headband.”

Denouncing the “military-industrial complex” of his time, he criticizes the unjust and useless wars and the danger of having permanent mercenary armies. “Whatever way things are presented, I think that a state has no interest in nourishing, for the preparation of a war which you only get when you want to get it, a vast mass of people of this type who threaten peace.”

Although in England the crime of theft will remain subject to capital punishment until the middle of the XIXth century, Thomas More, the philosopher that counseled his prince, and ended up being beheaded by his pupil Henry VIII, denounced this law as useless, perverse and radically contrary to the Gospel: “While God took man’s right away over the life of another and even himself, how could men agree on circumstances authorizing reciprocal killings?”

Three hundred years before Friedrich Schiller, Thomas More and Erasmus understood that a political revolution requires educating man to elevated forms of pleasure. After developing the pleasure of the body (health, and absence of suffering) he develops the pleasures of the soul, “which they (in Utopia) consider the first and most important of all, most of which stem from the practice of virtue and a conscience leading to a praiseworthy life.” Who cannot see, that those who spend their whole existence looking for the pleasures of the body, live an existence “not only ugly, but pitiful?”

“But everywhere they adopt the principle that a smaller pleasure should not be an obstacle for a greater (nobler) one; that it should never generate pain afterwards, and, it goes without saying, it should never be dishonest."

“But they think it madness for a man to wear out the beauty of his face, or the force of his natural strength; to corrupt the sprightliness of his body by sloth and laziness, or to waste it by fasting; that it is madness to weaken the strength of his constitution, and reject the other delights of life; unless by renouncing his own satisfaction, he can either serve the public or promote the happiness of others, for which he expects a greater recompense from God. So that they look on such a course of life as the mark of a mind that is both cruel to itself, and ungrateful to the Author of nature, as if we would not be beholden to Him for His favors, and therefore reject all His blessings; as one who should afflict himself for the empty shadow of virtue; or for no better end than to render himself capable of bearing those misfortunes which possibly will never happen.”

Mazarin |

More also outlines the basis for a concord between Church and State, a fundamental concept of positive laity, authorizing the freedom of conscience combined with a higher interest, as a dialogue of civilization. It is that concept that will serve as example for the process that called into existence the Edict of Nantes by Henry IV of France, extended to all of Europe as the peace of Westphalia by Mazarin and the Pope: “The Utopians have different religions but, the same way as several roads lead to the same place, all their aspects, despite their multiplicity and their variety, all converge towards the worship of divine essence. That is why one does not see, one does not hear in any of their temples, something that doesn’t accord with all the other beliefs. The particular rites of each sect can be accomplished in the house of each; the public ceremonies take place in a form that doesn’t contradict them in any fashion.”

And even: “Some adorn the sun, the others the moon or some planet (Reference to the Indians of the Americas). Some of them venerate as supreme god a man who while he lived radiated courage and glory.”

“The biggest number, however, and by far the wisest, reject these beliefs, but recognize a unique God, unknowable, eternal, incommensurable, impenetrable, not consisting of a body, but from power. They call him father and attribute to him alone the origins, the increase, the progress, the vicissitudes, and the decline of all things. They attribute divine honors to him alone.”

“For the rest, despite the multiplicity of their beliefs, the other Utopians at least agree on the existence of a supreme being, creator and protector of the world.”

The worst slander against More and Erasmus, exactly as those deployed against Lyndon LaRouche and his movement today, is the argument that all of this is very beautiful, and very idealistic, and precisely for that reason totally utopian and without any impact on real politics! Beautiful ideas have no effect on politics, since politics is ugly stuff and dirty business. Listen to Johan Huizinga, a reputedly great specialist of Erasmus:

“Despite a certain inborn moderation, Erasmus was a totally apolitical mind. He lived too far away form practical reality and had a too naïve an idea of the perfectibility of men to be able to understand the difficulties and the necessities of the state apparatus. His conceptions of good government were very primitive and, as often is the case for scientists strongly colored my morals, basically very revolutionary, even if it never came up in his mind to conclude that consequence. (…) He saw the economic questions in their idyllic simplicity. The sovereign must rule gratis and raise as few taxes as possible. (…) He reveals himself more realistic when he lists up, at the intention of the Prince, the works of peace: the improvement of the cities, the construction of bridges, of halls, of streets, and the draining of swamps, the diversion of the course of rivers, embankments, and the amelioration of the soils." For Huizinga, all of this has nothing to do with politics, because “here the Dutchman that is inside him is speaking…”

Erasmus in Italy and the League of Cambrai

And since we’re talking politics, let’s go there. Let us examine one of the most important issues at stake during Erasmus lifetime, that generally completely escapes the minds of many historians hiding underneath their academic mattresses, and nevertheless quite essential in understanding Erasmus.

Because a vast moneyed feudalism lay behind the mental feudalism grotesquely represented by the monastic orders and the earthly empires they were exploiting, one of whose neuralgic points was the Serenissima Republic of Venice. Generously harboring the oligarchic families that escaped from Rome after the sack of the city by the Gothic tribes of Alaric in 410 B.C., Venice, with Genoa and the Lombard bankers was the center of an international financial empire. Their method will be “divide and conquer” and their specialty the slave trade , commerce of indulgences, and the manipulation of wars. While the “catholic” Venice hires indispensable ships for to valiant crusaders with one hand, it does not hesitate to sell cannons to cruel Turks with the other. Erasmus describes the nature of the “beast” in one of his Colloquia, The friend of the Lie and the friend of truth and he is not the only one to do so: as early as 1501, in Blois, the King of France, Louis XII and the Emperor Maximilian plan to bring the dominance of Venice to an end.

In 1506, Erasmus goes to Italy as the preceptor of the children of Henry VII personal physician, and is present in Bologna at the unforgettable spectacle of the warrior pope Julius II, armed from top to toe, at the heads of the troops, enter the city. Nothing but viewing the “Vicar of Christ” heading an army in harness and waging war on Christians, convinces him of the real nature of Julius' character.

Aldus Manutius |

Erasmus will be in Italy during the decisive moments. Firs, at the end of 1507, he introduces himself in the printing shop of Aldo Manuzio (1449-1515), great editor of Aristotle whose workshop and salon became the obliged meeting point for many erudite intellectuals. There he meets many Greek scholars, in particular Jean Lascaris (1445-1534), librarian and ambassador of Louis XII. Manuzio, whose printing shop is financed by a future detractor of Erasmus, Prince Alberto Pio de Carpi (1475-1531), lodges him at the house of Asolani, his father in law. Erasmus shares his room with the young Greek and Hebraic scholar Aleandro and the food is of such a dubious nature (according to his Colloquium Sordid opulence) that he becomes ill.

Girolamo Aleandro (1480-1542), another descendant of an important Venetian family, was a literary member of the Aldine academy and to become the legate of the pope in charge of fighting “heresy." He engages in a real witch-hunt against Erasmus, whom he hates with a passion, because Erasmus would not betray the ideal he shared with him. It is quite likely that the unleashing of this witch-hunt was a direct political answer by the Venetian oligarchy. At one point Rabelais sends a letter to Erasmus offering to help him against Aleandro.

Then, on December 10th 1508 in Cambrai, a heterogeneous alliance is formed against Venice uniting different parties, alas, more interested in their possessions than in the future of humanity. Louis XII, protector of Leonardo da Vinci, dreams of taking over Milan, since he is descended from the Visconti family. Pope Julius II, great lover of a “triumphant Catholicism” want to take back the Romagna region and the city of Ravenna, occupied by the Venetians. Other princes and lords will enter the coalition.

On the battlefield of Agnadello, on May 14th 1509, the League of Cambrai gives a crushing defeat to the 40,000 Venetian forces. To celebrate that victory, the King of France, orders immediately Leonardo da Vinci to prepare the official festivities.

In Rome, Julius II’s nephew cardinal Raphaël Riario (1460-1521) asks Erasmus, on stay in the eternal city, to suggest action on the situation. Erasmus advances two strategic memoranda, whose strangely have disappeared. It seems that one memorandum explained how to make peace, while the other stipulated how to win the war, which was the same thing. According to Melanchthon, Pope Julius II allegedly said that Erasmus “definitely didn’t understand anything about worldly matters.”

Agostino Chigi |

Julius II, himself a Ligurian and visibly favoring Venice’s competitors, the Genovese, sends in Agostino Chigi with an emergency program to solve the crisis in March 1511. Agostino Chigi (1466-1520), of Siena, probably the richest man on the planet at that time, was the Pope’s banker who fixed his 1504 election in the first place, by buying the votes of the Cardinals .

Chigi pressures the Venetians to give up their monopoly on the imports of alum, a strategic raw material imported from Turkey and sold all over the world by the Venetians. Alum is a mineral salt indispensable for binding dyes to cloth and glass manufacturing.

On April 15, Alvise da Molin, a member of the Savi (Venice’s real government: the Council of the Wise) outlines the following proposal to the Pregadi (Senate): if from now on, Venice should buy its alum exclusively from the papal mines in Tolfa, 70 kilometers north of Rome (and tax-farmed by Chigi for the Curia), the banker will give security for a loan of 40.000 ducats allowing Venice to hire the Swiss mercenaries necessary to defeat the League of Cambrai, now on the verge of entering the city. Faced with such a choice, the Savi of Venice, grudgingly but politely accept the deal in the name of the survival of the state.

Julius II then makes a spectacular shift in his alliance, and enters a coalition with the Venetians to chase the French “barbarians” out of Italy. On October 5th, 1511, the Holy League makes that alliance official and goes into action. “If Venice didn’t exist," said the pontiff, “we would have to invent it.”

Dominico Grimani |

In Rome, the Venetian Cardinal, Domenico Grimani (1461-1521), son of Antonio Grimani (later Doge) and intimate friend of the banker Chigi, puts his house and rich library of 8,000 volumes at the disposal of Erasmus in a desperate effort to keep him in Rome while kindly reminding him of the fragility of his health.

Erasmus refuses the tempting offer and leaves for England. In less than a week, he writes “In Praise of Folly” that he gets printed in France. The humanists lost a battle, but now they had to win the war. A new flank came up on the other side of the channel. Henry VII just died and now Thomas More’s protégé, the young well-educated Henry VIII, which whom Erasmus had exchanged poems when the prince was still a boy, is the new King.

In Rome, in commission of Julius II, Bramante gets the order to rebuild Saint Peters basilica, Raphael is commissioned to paint the Stanze and decorate Chigi’s villa, while Michel-Angelo is sent to Carrara to choose the blocks of marble for Julius II’s mausoleum, a pope whom Rabelais will put in hell, as a miserable vendor of little pastries, a pope who will be the subject of a satirical writing called Julius Excluded from Paradise, a piece of which Erasmus said “the author was a fool, and the printer even more foolish.”

Encourage Luther to destroy Erasmus

Lucas Cranach, Portraits of Luther and Melanchthon, 1543, Gallery of the Offices, Florence. |

If is often said of Erasmus that he “laid the egg that Luther hatched;," it would be fairer to say that Luther entered as a fox in a poultry farm and that the Venetians gave him the key! Luther’s sudden rise to fame and power was the perfect pretext for crushing Erasmus and his large influence for peaceful reform of the Christian world.

History promptly accelerates in August 1514, when Albrecht of Brandenburg is promoted Archbishop of Mainz. To cover the costs of his installment, he concedes a plenary indulgence (the total remission of sins) in exchange for money, the scheme organized by the Fugger bank of Augsburg, a banking dynasty entirely trained by Venice’s Fondaco dei Tedeschi (German House).

Half of the profits went to Albrecht; the other half went to Rome to finance the reconstruction of Saint Peter’s basilica. The Dominican preacher Tetzel even claims one can absolve the dead, even without prior confession! The historian Michelet documents how, by paying in advance, one could obtain the remission of sins… still not yet committed!

The scandalous exploitation of this pseudo-religious financial racket was the shameful subject behind most of those days’ theological debates. Some would hypocritically speak in favor of the “immortality of the soul," not for bringing each to his or her responsibility in the face of eternity, but to have a market for selling indulgences! These indulgences, which were considered “good works," made it possible for everybody to buy back his sins thanks to one’s “free will”!

Erasmus had already lambasted these practices in his In Praise of Folly, published in 1511, and the scandalous nature of it might have been deliberately over-publicized to force into the open a crisis favorable for his enemies. Isn’t it strange to hear in 1516, at a point Erasmus estimates victory near, since his faction is becoming largely hegemonic, the Venetian Aleandro writing in a letter from Germany to Rome that “here, many expect the coming of a providential man to open his mouth against Rome.”

Hence in 1517, Luther writes his 95 thesis’s attached to the doors of the Schlosskirche of Wittenberg. Undoubtedly, all of this had created a situation where anybody shouting powerfully that man’s salvation could only come from faith and faith alone (the individual in a direct relationship with God, without the need of sacraments), would easily gain huge popular support. In a strange way, and without Luther’s having suggested or desired it, the theses were immediately translated and published in German and reached the entire country in less than a month, an extraordinary short time for that period.

Then, in 1518, redeveloping the theme of the radical Thomist, Savonarola, Luther presents his doctrine in Heidelberg . While attacking the predominance of Aristotle in theology, he affirms the sinful nature of man and denies the existence of the human will. Pope Leo X convokes Luther to answer his special envoy in Augsburg, Cardinal Cajetan, and the audience takes place at the headquarters of the Fugger bank in Augsburg (!) Luther refuses to recognize his errors. To discredit Erasmus, he voices the latter’s demand for a general Concilium in order to abolish all the bad practices.

The headquarters of the Fugger Bank at Augsbourg. |

Erasmus immediately grasps Luther’s role as an agent-provocateur, since he’s now between a rock and a hard place, between “Scylla and Charybdis." Lutheran radicalism will offer the desired pretext for organizing the repression against the humanist faction and Erasmus writes: “Nice defender of the freedom of the Gospel! By his fault, the yoke that we carry will become twice as heavy. What otherwise was nothing but a probable opinion in schools becomes already truth of faith. It becomes dangerous to teach the Gospel… Luther acts as a desperado; his adversaries excite him as they please. But if we assist at their victory, nothing will be left to us except to write the epitaph of Christ who will not be resurrected.”

In order to escape the infernal logic that has been unleashed against him, Erasmus is now obliged to undertake simultaneously a bold offensive on different fronts. First, he appeals to Luther for moderation. At the same time, he asks the elector Frederic of Saxony to not deliver up Luther as long he’s not condemned by a university. Meanwhile, Erasmus republishes his own “Enchiridion” doing all his best to bring the debate back to the real challenges in front of Christendom, challenging those in Rome to finally listen to him, Erasmus. The crisis provoked by Luther proves his case: if the Church and Rome do not accept immediately his proposals for gradual and pacific reform, they will become accountable for incessant violence and useless bloodletting. He restates the case in a letter to More in 1527: “I fear that very soon, the fire that is heating up now will break out and turn the world upside down, since so is it called for by the arrogance of the monks and the violence of the theologians.” Immortal Venetian Rome smartly intends to use Luther against Erasmus, and opens a publicity debate with Luther, downplaying Erasmus.

In 1519, Luther, looking for financing, launches his Manifesto to the German Nobility concerning the reform of the Christian state, propitiating the newborn nationalism and the discontentment of the peasants. He refuses the distinction between clergy and the faithful, demanding the right of free examination given to all, denying the Pope the right to convene Conciliums, since that is a prerogative of the Princes. By wedding himself to a nun who will bear him six children, Luther flatters the values of the family so beloved by the peasant world. And, to head the family, no need for hierarchy, no intermediary, just a Bible. A book to replace a man: take this and read it !

In 1520 in a few months, Luther’s three major works, including On the Babylonian captivity are printed in Augsburg, the hometown of the Fuggers. At the end of the year, Luther burns the papal bull that condemns him and in early 1521, he is excommunicated by Leo X. At the request of Erasmus, who’s not very happy with the game, the Elector of Saxony hides Luther and protects him at the Wartburg castle. Erasmus knows that if Luther falls, his entire reform project collapses with him, and the world risks going straight to war. In the meantime, Erasmus succeeds in maneuvering his friend, the moderate Melanchthon, to be the leader of the Lutheran faction. Melanchthon will write a catechism for the reformers while always remaining open to honest compromise and reconciliation with Rome.

Charles V. |

On May 8, 1521, Charles V issues the first edict which condemns anyone who dared to print or even to read the books and Bibles of Luther for heresy. All those violating that edict were guilty of laesa majestas divina (treason to God, a terminology identical to that of Pope Innocent III against the Cathar heresy of the XIIIth century). To establish the equivalence between heresy and state treason, a capital crime, an unusual type of jurisdiction completely foreign to the common law system of the Burgundian Low Countries was introduced. By this procedure heretics delivered to the “secular arm," solely authorized to dispose of the life of the condemned.

The Duke of Alba. |

Is it not strange that the papal bull outlawing Luther’s books and inciting their burning was initially uniquely reserved for the Burgundian Low Countries, a newborn nation-state and the fatherland of Erasmus, and not at all to Luther’s Saxony! Charles V desired to remain friendly with the German Princes whom he needed in his war against Francis Ist, the historians will explain.

The application of these emergency laws will harvest such an opposition of local magistrates, that Philippe II will be obliged to send in the bloodthirsty Duke of Alba to apply the decisions of the Bloedraad (Blood Council, or Tribunal of Troubles), the which will ultimately provoke the overthrow of the Habsburg occupation.

“I find death more pleasing than servitude” (Erasmus in a letter to More)

In Leuven, where Erasmus works, Niklaas Baechem van Egmond, a Carmelite prior of Antwerp who will soon head of the Inquisition, states that “as long as Erasmus refuses to write against Luther, we consider him a Lutheran” and a rumor campaign, started by Aleandro, accuses him of having written Luther’s De Captivitate Babylonica.

All those who held back from attacking him when they believed him protected by kings and popes, now unleash their hatred. The worst being the sly “friends," the jealous, the second violins and those that Erasmus calls, adopting Plato’s terminology, “the hornets” (i.e. sterile, and generally raging theologians). Despite all this, he declares that “neither death nor life will detach me from the community of the Catholic Church.”

His friends fear for his life and ask him to write against Luther…or to join him. Nothing more troublesome, than to preach reason and moderation. Working in Leuven in this climate becomes impossible and he leaves for Basel in 1522 to find a group of friends around the printing shop of Johann Froben (1460-1527).There, he reworks the “Colloquia," funny, but elevating little dialogues originally written before 1500 in Paris for the purpose of teaching Latin to youngsters of wealthy families. Having understood that his adversaries were in reality far more preoccupied with their own personal career, reputation and lifestyle than with any form of truth relative to the future of mankind, Erasmus integrated his detractors personally in these little satirical pieces.