SCHILLER INSTITUTE CONFERENCE

Building A World Land-Bridge:

Realizing Mankind's True Humanity

Thursday, April 7, 2016, 9:00am - 9:30pm

NEW YORK CITY

Panel I: The New Silk Road Becomes the World Land-Bridge

Li Xiguang: Creating a Dialogue of Cultures on the New Silk Road

by William Jones, EIR News Service

EIRNS/Stuart Lewis

Professor Li Xiguang addressing the April 7 Schiller Institute conference. |

Program and video

Invitation

![]()

Download slides used in this presentation

as a Microsoft Power Point file

(25.3 MB)

A PDF version of this article appears in the April 15, 2016 issue of Executive Intelligence Review and is re-published here with permission.

April 10, 2016 —Speaking at the Schiller Institute conference in New York on April 7, Professor Li Xiguang, the director of the Tsinghua University Center for International Communication Studies, engrossed his audience in the saga of his extraordinary quarter-century of total personal devotion, as a leading Chinese personality, to the New Silk Road project. Professor Li brought the New Silk Road proposal of China’s President Xi Jinping, the so-called “Belt and Road,” vividly to life. Over 26 years, Professor Li has travelled the Silk Road with no fewer than 500 of his students.

While the proposals of the Silk Road Economic Belt through Central Asia, and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road through South and Southeast Asia, have a predominantly economic content, they are also strategically important for China as its political influence grows, Professor Li noted. The hostile attitude taken by the United States to China’s long-suppressed maritime territorial claims, mobilizing the U.S. Navy and the forces of its military allies in the region,— including a revitalized Japanese force projection,— is an attempt by the United States to create a strategic “cordon sanitaire” along the Pacific Rim, in which patrolling U.S., Japanese, Australian, and Filipino naval vessels will potentially threaten to cut off China’s free access to the surounding seas.

Access to the Oceans

Faced with this problem, Professor Li explained, China is concentrating on creating ocean access toward the West and Southwest, preparing to build major ports in the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Pakistan. While the United States is also doing its best to rally these countries in its attempt to limit growing Chinese influence there, these nations are not engaged, as are Japan, the Philippines, and Australia, in a direct military alliance with the United States. Even India, which is being heavily courted by the United States as a hedge against China, is presently not a military ally of the United States, and has had, in spite of recent tensions, a long-term political and cultural relationship with China.

“Helga talked about a South China Sea potential war, and China worries about a potential conflict with U.S. and other naval maneuvers in the South China Sea, and worries about an American naval blockade of the Malacca Straits,” Professor Li said. “So China wants to have a new Maritime Silk Road which will not pass through the Malacca Strait, and as a result, China is now building four ports in countries along the Indian Ocean. One is the Kyaukpyu port in Myanmar, another the Chittagong port in Bangladesh, Colombo port in Sri Lanka, and Gwadar port in Pakistan. And so far, China has completed construction in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and also the Gwadar port in Pakistan.

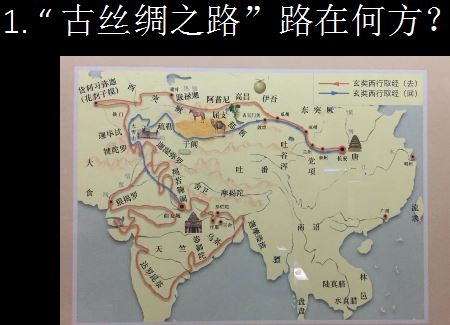

View full size Professor Li Xiguang

Map of Xuanzang's 15-year expedition. |

“And this is the ancient Silk Road. In China, the explorer Faxian (337-422) is a household word, and even more so Xuanzang (602-664), who was a Tang Dynasty Buddhist monk. He traveled from Xian, Xi Jinping’s home province, through China’s Xinjiang Province, climbed over the Tian Shan Mountains, and walked into Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Bukhara, and Khorezm, and through Afghanistan and through today’s Pakistan into India. He spent something like 15 years on the road. And eventually he brought back 600 copies of Buddhist scriptures on elephants and on horses. And that is why Xian was so famous, because it has the oldest stupa, or Buddhist pagoda, built for this monk.”

(Xuanzang’s trip was made more difficult by the necessity, in the Tang Empire, to obtain permission to travel abroad, which the lone monk did not have. But in spite of the obstacles, he was determined to travel to India and bring its lessons back to China. His trip is also widely known through the somewhat fanciful description, based only roughly on Xuanzang’s actual adventure, of the famous Ming Dynasty novel, Journey to the West. There a Monkey King becomes the monk’s guide, taking him through all sorts of miraculous adventures. It is considered one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature. The story, retold in film and on television as well as in children’s books, is known and loved by all Chinese children.)

Twenty-six Years on the Silk Road

Professor Li certainly knows whereof he speaks, since he has traveled extensively over the route of Xuanzang, and the entire Belt and Road region, for the last 26 years. “In 1990, that is 26 years ago, when I was a young scholar of the UNESCO Silk Road Project, I started my journey following the footsteps of Xuanzang of the Tang Dynasty. Ever since then I have been travelling and writing on the Silk Road, as a journalist and also as a journalism educator.”

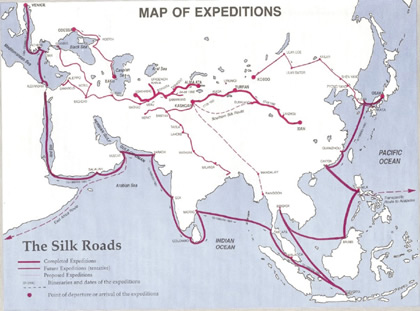

View full size Professor Li Xiguang

Portions of the ancient Chinese silk routes that have been traversed by Professor Li Xiguang over the past 26 years, accompanied by no fewer than 500 of his students. |

Since then Li Xiguang has also taken many of his students on trips to the Silk Road regions; he showed the Schiller Institute conference many pictures of sites they had visited along the ancient Silk Road. “And in this winter vacation, a month ago,” he said, “I took our students to Kolkata in eastern India, and also Bangladesh. This was a really hard-travelling class; the students were so tired that at night they slept on the bus. Except me: I just kept a watchful eye on the driver; the Bangladesh drivers were crazy. [laughter] So I had to talk to him constantly so he would not fall asleep like the students.”

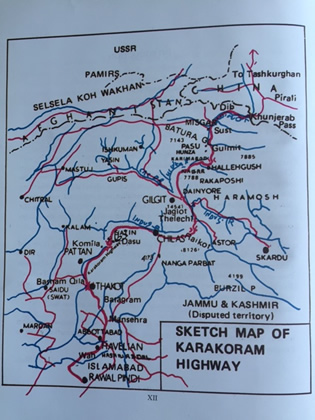

Professor Li identified three main corridors moving down through South Asia. The first, and the one that is most advanced presently, is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). “It goes through the western part of the Himalayan Mountains, that is, the Hindu Kush Mountains and the Karakoram Mountains,” Professor Li explained. “And China had already built a highway there in the early 1970s [see map, p. 39], but China and Pakistan are planning to build a railway and a gas pipeline along this Karakoram Highway. And the Karakoram Highway, starting from China’s westernmost city, Kashgar, now ends in Islamabad, Pakistan. But the corridor will be further extended through Pakistan’s Khyber Pashtu province and Gilgit-Baltistan region, all the way to Gwadar port in Pakistan.”

View full size Branches of the New Silk Road Economic Belt. Note the three routes from China into the orange region. The westernmost, the CPEC, is most advanced. The easternmost passes through Myanmar (lavender) into Bangladesh, and the middle passes through Tibet into Nepal and ends near the border with India.

Professor Li Xiguang |

The second route is the China-India-Bangladesh-Myanmar Corridor. But a lack of firm commitment on the part of India—under intense U.S. pressure—to develop this corridor, has been an obstacle. “And Bangladesh gave some support originally,” Li said. “The Chittagong port construction has been signed and China has sent its construction team there, but according to Indian press reports two months ago, it was suddenly stopped by the Bangladesh government. The Bangladesh government decided to cooperate with Japan to build a new port only 25 km from the Chinese-planned port in Chittagong. And India is strongly against this Chittagong port, regarding it as something in India’s backyard.” The third corridor is the China-Tibet Railway corridor, which now ends near the Nepal and Indian border.

A Proposed Cultural Belt

View full size Professor Li Xiguang |

Given the difficulties presented by U.S. hostility, Li has proposed a Cultural Silk Road Belt along with the Economic Belt. “What is the basis for the Cultural Belt along the Silk Road?” he asked. “Actually, the British sources—I mean the academic sources doing research about the Silk Road—the American sources, Indian sources, and Chinese sources, they all have their sources in Chinese books by Faxian, by Xuanzang, by all these monks; they’re more accurate, actually than Marco Polo’s records.

“So from reading these ancient source documents and also doing our own research, we found that we share more things in common than differences; I see more identical elements, instead of differences. Like India-China relations: Actually, one of the three key elements of Chinese culture is Buddhism. Buddhism comes from India. And with Pakistan. Pakistan is a Muslim country and China has 20 million Muslims, like in Xinjiang, in Gansu, in Ningxia, and Qinghai; these are all Muslim provinces very close to Pakistan. I regard this as a resource for the Belt and Road. I never regarded Muslims as bad elements, or as some potential threat. That’s why Pakistan, actually, in the Chinese mind and in the Pakistani mind,— Pakistan and China are the closest allies. If China has one ally, it is Pakistan and no other country. That is totally different from American mentality in this regard.

View full size Sculpture of the Buddha from the Gupta period of India in Pakistan .

Professor Li Xiguang |

“And we’re also connected by Buddhism and by language with Central Asia, as China maintains a number of autonomous regions. With the Uzbeks, we have our own Uzbek autonomous region, and with Tajiks, who are Iranian-speaking people, we have our Iranian-language autonomous counties in Tashkurgan, in the westernmost region. So we share many things in common. So if we utilize these common things we share, they could serve to build a Cultural Belt.

“And Xi Jinping in his official statement said that he wants to build a Silk Road, and he said that top priority for China’s foreign policy is to build a community of common interests of neighboring countries and China,” Li continued. “That has been interpreted by some Chinese scholars, as being different from the policy of previous Chinese leadership; the previous leadership regarded Chinese-American relations as the top priority. But now we regard the building of a community of common interests of neighboring Asian countries as the top priority in foreign policy. And I also said it is a community of common faith. But in my study, I proposed that the base for a community of common faith and community of common interests, should be a community of common value, a community of common security, and a community of common culture—a big culture, not a small culture.”

View full size Xi Jinping (middle), between the President and a Senator of Pakistan, April 2015, signs agreement with the President of Pakistan to create the Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Professor Li Xiguang |

Li Xiguang has here given a firm confirmation of the need for what Helga Zepp-LaRouche has been calling for: transforming the “Belt and Road” into a new paradigm for mankind, a new paradigm in relations between cultures, building on the highest achievements of each of them. And the Schiller Institute conference in New York showed that there is the clear possibility of bringing the United States out of its enthrallment with a Cold War and British imperial mindset, and back to the traditions of Alexander Hamilton and John Quincy Adams, in which the nations of different cultures—and different forms of government—can, and must, work together to realize the common aims of mankind in economic development and mutual cultural enrichment.