SCHILLER INSTITUTE CONFERENCE

Building A World Land-Bridge:

Realizing Mankind's True Humanity

Thursday, April 7, 2016, 9:00am - 9:30pm

NEW YORK CITY

Panel III: Classical Culture: The Only Basis for a Dialogue of Civilization

Verdi’s Operas and Italy’s Risorgimento Movement

presented by Carmel Altamura

EIRNS/Stuart Lewis

Carmela Altamura. |

Program and video

Invitation

A PDF version of this article appears in the April 22, 2016 issue of Executive Intelligence Review and is re-published here with permission.Dennis Speed: For about a year, members of the Schiller Institute have been involved in the creation of citywide choruses, and we’ve done some performances of the Handel Messiah; we’ve done two in Brooklyn and one in Manhattan. But in the course of work that we were doing, one of the members of the Schiller Institute, Mr. Lyndon LaRouche, kept talking about what he called “the Italian principle.” He said that if you really want to do this right, you’ve got to assert the “Italian principle,” the placement of the voice, the proper placement of the voice. And when I met the next speaker, without any of that being said to her, this was what she was simply talking about. She has known this; this isn’t anything new to her.

Now the reason this becomes very important is that Classical culture, when performed properly, is the most powerful weapon for oppressed people in the world. To speak on the topic, “Verdi’s Operas and Italy’s Risorgimento Movement,” I’m pleased to welcome to the stage Carmela Altamura, soprano and vocal instructor, founder and director of Inter-Cities Performing Arts and of the Altamura/Caruso International Voice Competition.

Carmela Altamura: Ladies, Friends, what a joy! The energy in this room is enough to transform the world. Congratulations to all of you for having taken time, love, passion to create something that will last forever. Because it is love that moves all of your genius. It is love! The whole world moves on love.

The founders, Mr. and Mrs. LaRouche, are to be venerated, congratulated, and all of the guests, the speakers, the performers—and you, all of you are accomplished, all of you are geniuses.

And so, I’ll tell you a few words now. In 1987, the idea came to me, after having worked for 14 years in a school for the community, for dispossessed, and for the expatriates of the communist world. Since the population began to change and the Cubans moved to Florida, I thought it was time to close the school and create a company called Inter-Cities Performing Arts, Inc. It became a compulsion, became a drive for me to create something, to improve ethnic, social, professional, and cultural relations in the world, through the arts. And so two programs were born out of that: The Altamura/Caruso International Voice Competition, and the school, the Altamura Center for the Arts, where the winners of these competitions would have the opportunity to have advanced studies and meet and encounter the real masters who would transmit the wisdom—not written—by voice; this is the tradition of the bel canto.

You cannot write everything down anyway. The word, unless it’s married to music, has its own limitations.

I made a few innovations that caused a little stir in the world. I took away the age limit. That came like an atomic bomb in the cultural world. “What on Earth is this lady doing! What is she talking about?” Well, there was a need to do that, because very important voices which are needed for the Verdi, and Puccini and Wagner repertoire, mature later—psychologically, physically, hormonally—and I saw that need.

What happened after that—even though I took a little abuse, but I have thick skin—we discovered great, great voices, which today are performing in the major, prestigious theaters of the world, such as the bassi, the dramatic sopranos, and mezzosopranos, the contralti, and the coloratura, you know.

This is why I feel attached to Verdi, because of this impact. I took the winners to Milano, to the home for retired artists, which Verdi founded. He was a great humanitarian and philanthropist. He founded hospitals, he founded this rest home, and there, my singers were immediately booked for La Scala to do Attila. You know, Attila requires a very heavy voice.

My competition took its place in the world. I raised the bar, and I chose Giulietta Simionato; I don’t know if any of you know her, but she was the premiere mezzosoprano at that time in the world. In order to raise the bar right away, my first competition took place at the Lincoln Center. And I had nerve—I was nervy—and I wrote to the United States Congress. I said: “If La Scala gets a letter from the United States Congress, maybe they will listen.” And so, they let her go, and she came to the United States and became my first president of this competition.

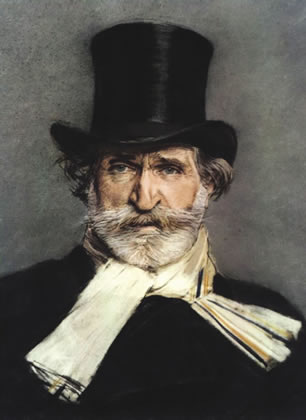

Giuseppe Verdi: The Voice of Italy

National Gallery of Modern Art/

Giuseppe Verdi by Giovanni Boldini Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) |

And of course, I am very enamored—ever since I was a little girl—of Verdi. I remember my father taking me to Palermo; I was only six. I saw Rigoletto, which frightened me; the hunchback frightened me terribly, but when Gilda came out, I immediately memorized “Tutte le feste al tempio.” And in my hometown, they put me on a little tobacco box, and I would sing. Of course, I would get lots of candy, so I sang “Tutte le feste al tempio” from one corner of the town to the other end. And then, at the age of eight, after the world war, I came to the United States, and on that ship they discovered me.

But anyway, I’m not here to talk about myself, I’m here to talk about Verdi and the Risorgimento. Verdi is the voice of Italy. He’s the unifying voice of Italy. When Verdi was born in 1813, the land was under French rule; it would only last another year, because then Napoleon was defeated. And little Verdi, being a child of destiny—I should tell you this little story, because I think that men of destiny are born under a special star, especially if they are to do something transformative for the world.

He was barely a week old, and the Austrians invaded, to push out the French. They hired the Cossacks: nothing new under the Sun—to speak about ISIS, forget about it. They were worse! So the priest said to the poor women, “Go into the church, there you will be safe.” So all the women and the babies went to the church. And Luigia Uttini, which was the name of Giuseppe Verdi’s mommy, went also, with the child in her arms, but she decided not to stay in the church; she decided to go the sacristy, and from the sacristy she saw the stairs going to the belfry. She climbed the stairs all the way up to the belfry; the child never cried. In the morning, when the Sun came up, there was complete silence. She went down the steps. She thought by now, everybody’s gone. And when she came down, she saw, everyone had been slaughtered. Only little Verdi and she were alive.

Now, if you go there today, to that church, there is a plaque, that tells you that this is a very special place.

At the age of three, he was studying Latin, math, Italian. Imagine! Now, the father, realizing that this child was highly musical, went out, and on his back, carried this little piano—you know, it was no bigger than me; now it’s at La Scala, on permanent display. And he brought it to the child. And the child began, and he suddenly started to make little melodies, and with the left hand—by now he was six. And the people in the tavern said “doesn’t this child ever stop playing?” “No! He’s got this passion for the music!”

And little Verdi, at the age of eight, was deputizing for his teacher, who was ill at that time; he took his place in church, to take care of all the church functions, and weddings and funerals. Can you imagine that? And he took his stipend, and he brought it to his parents. Try to find that today.

He helped his mother gather the mulberry leaves; she produced the silk worms, and the poor child, he would go with his big basket on his back, and bring all these leaves to his mother, trip after trip after trip.

So these are the little stories.

Now, they take Verdi for advanced studies in Milano. But before he goes to Milano, he goes to Busseto and Mr. Barezzi, a prominent businessman, decides to take him under his wing. It was evident that this child was extraordinary, so they sent him to the Conservatory. And he auditions: They did not accept him.

Verdi was heartbroken. And so was Mr. Barezzi. But they would not give up because they knew this was political. The judges said, “His hand does not sit properly on the piano, and his compositions, maybe if he studies some counterpoint, someday he might become a veritable composer.” “Veritable?” He wrote 27 operas. He never made it to the Conservatory. So I should tell the students, never get discouraged. Just work, work, work, work, and persistence, and perseverance, that’s the gift.

And Verdi gets married to Barezzi’s daughter, who was a soprano. Her name was Margherita, a beautiful girl, very holy. They have a little girl, Virginia, who twelve months later dies. They try again and have a little boy, Icilio. Eighteen months later, he dies. Discouraged, disappointed, and depressed, they go back to Milano looking for work. His wife Margherita sells even her jewelry; he doesn’t know about it. She sells everything, and Verdi never knew that. Then she falls ill, and she dies.

‘Va Pensiero’

Before this happened, he meets a soprano by the name of Giuseppina Strepponi, a very famous star at La Scala. And Giuseppina recognized this great talent, and she goes to Merelli who was the general manager of La Scala, and he believes her, and so he gives Verdi a commission for the first opera, Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio. Verdi had it in his blood. So this was 1840. He had it in his blood.

He is commissioned for 14 operas; not bad for a young composer. But, when his wife dies, Verdi puts down the pen, and says, “No more. I will not write another note.” And dejected, depressed, sorrowful, and sick to the core of his heart, he moves into third floor loft apartment, cold flat, and he finds some chestnuts, and that’s all he had.

But then there is destiny. It happens that the general manager of La Scala has a libretto in his hands, but that his chosen composer refused to do it. So he sends someone to fetch Verdi, who does not want to go at first. Some stories say it was Giuseppina, and others say that he sent someone else. But Verdi did go. The general manager told him that he had a beautiful script, “it is wonderful!” It’s about the exiled Jews, and Verdi says, “So what?” “No, this is very important, I want you to read it.”

“I told you, I will not write another note.”

“Listen to me, this is good. Go!” He puts it under his arm, shoves him out the door, and Verdi, with the libretto under his arm, goes home. He throws the libretto angrily on the nearby table. Do you know where it opened? Verdi looks, and he reads, “Fly, thought, on golden wings,” the translation of “Va pensiero, sull’ali dorate.”

Verdi closes it again—“No! No, no, no, no!” and he goes to bed. After fifteen minutes, he gets up again . . . what? What was that? And he reads it again. Hmm, well, I suppose I could write a few notes. He goes to the piano, and he puts down a few notes. And he writes the melody, renowned all over the world, “Va pensiero, sull’ali dorate.” He takes it back to La Scala, and about a year later, the opera is being produced, and Donizetti—do you know Donizetti?—he was in the theater at the time; it was a Thursday. And a mechanic said to him, “Listen, go. You’ve seen the rehearsal already.” He said, “No, no, I’m staying here.” When it was time to perform the “Va, pensiero,” all the people that worked in opera house, they froze! And on Sunday, they performed the opera [Nabucco]. And from being an unknown,— soon every little barrel organ in Milano was playing the melodies. All the sauces were “alla Verdi,” the hats were “alla Verdi,” the clothes were “alla Verdi,” and his career began.

Verdi said, “I never had peace after that.” All I did was work like a dog. He never saw the sunlight.

The woman who really helped him though, was the Giuseppina Strepponi, with whom he lived for 10 years.

Unifying Italy Through Beauty

Search the LaRouche Publications Store for "tuning" |

Now as for the Risorgimento, the movement that unified Italy, Verdi was in communication with Mazzini and Garibaldi, and Alessandro Manzoni, who at this time had written the novel, I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed), and had given Italy its language! And so every opera that Verdi wrote after that—I Lombardi alla Prima Crocciata (The Lombards on the First Crusade), Giovanna d’Arco (Joan of Arc)—every opera was written on the subject of the tyranny of the reigning house.

Italy becomes one. Italy becomes unified, and in 1870, we now have a country called Italy.

Verdi’s name, when he was baptized, was Giuseppe Fortunino Franceso Verdi. And through him the country was unified, the Italians were unified, and he loved everyone who had helped him.

But, Ladies and Gentlemen, there is something I want to read to you tonight, and I want to leave you with this story. Tonight, everyone spoke about nature, about unity, about oneness. There is one in Italy who happens to be the patron saint of Italy; it is St. Francis of Assisi. We are in the middle of the Thirteenth Century. These words are religious, but the wisdom is the same for every religion. But they go beyond religion, they go to the core of truth, and truth is not learned, Ladies and Gentlemen, truth is revealed, and it is revealed only to those with a pure heart.

This is called the “Prayer of St. Francis”:

“Lord, make me an instrument of thy peace.

Where there is hatred, let me sow love;

Where there is injury, pardon;

Where there is doubt, faith;

Where there is despair, hope;

Where there is darkness, light;

Where there is sadness, joy.

O divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

To be consoled as to console,

To be understood as to understand,

To be loved as to love;

For it is in giving that we receive;

It is in pardoning that we are pardoned;

It is in dying to self that we are born to eternal life.”

This is the message of oneness: If we all take a little responsibility, each one of us, the world will be transformed. It is time, or it is too late.