Schiller Institute Conference September 15-16, 2007 Kiedrich, Germany Civil Rights for All People of the Planet Amelia Boynton Robinson |

EIRNS |

Amelia Boynton Robinson's presentation opened the conference panel on "Rebuilding Civilization," on the evening of September 16. She is a heroine of the civil rights movement, and today serves as the vice chairman of the Schiller Institute in the United States. In this capacity, she travels far and wide to keep alive the message for which she has fought for more than 70 years: the civil rights of all mankind, and the spirit of love for one's neighbor. She was introduced by Helga Zepp-LaRouche. This transcript has been abridged.

Helga Zepp-LaRouche: I don't think I need to explain who she is. She was the person who brought Martin Luther King to Selma. She was fighting for civil rights long before that, between the 1920s and the '30s, and she is an inspiration of all good people around the world, in the many countries she has been travelling to in the recent years.

Amelia Boynton Robinson: There is nothing in the world I like better than to talk to young people. And when I say young people, I think of everybody as being young. Nobody's as old as I am, so everybody else is young!

When we think of the disasters that we have had throughout the world, many people have said, "We need to do something. God must be angry with us." Because I think in the United States of America, we've had fires such as we've never had before. We have had rivers that have swollen, and overrun some of the towns in Texas. We have had a volcano, and we have had so many other disasters. But the worst disaster we have had, is the young people who are going astray. And many of them are going astray because of the fact that the system is using that as a form of genocide, and the poor things don't even know it.

I have talked with people, young people, who have been involved with bebop music, and whatever you might call it. And many of them have said that they were doing all right. But, the people who are trying to destroy them, which are the oligarchies, people with money, say, "Well, your music is all right, but the words—if you just sing the words"—filthy words, if you know anything about the American type of music now—"I'll pay you so many millions of dollars." And they have lost self-esteem, race pride, and are going after money. It shows you that money is not everything....

So, I think that we are kind of cleaning up. And not only cleaning up that. You [in Europe] are not having the trouble that we have had with the dress code of young people. One young man was introducing me in a school, and he had his pants below his waistline. I said, "Son, go on into the bathroom, and get your pants up, because they're about to fall off." I asked, "Why is it that they are wearing their pants without a belt?" They said, "That's the prison style." When people go into prison, they will not let them have a belt, because they might hang themselves, or they might make a rope and escape, or something. And to think that the young people are so brainwashed that they figure that this is the style, and they imitiate prisoners in the jails, and in the prisons.

So, we are trying to clean up all of this, and give young people self-esteem, give them pride, give them encouragement to do something, because every person who is born, has a little bit of genius somewhere about them, and it is up to us, to get it out.

Now, I did not write a speech, but I have had several people say to me, that I hope you will speak about this, or speak about that. So, I'm going to try to do it....

Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King

Someone asked me to talk about Dr. King.

Rosa Parks

Martin Luther King, Jr.

I think I worked with Dr. King almost as closely as anybody. First, we have to realize how Dr. King became so popular. And it happened because of a very, very mild and meek woman, whose name was Rosa Parks. And I feel sometimes that that bridge that we crossed, where I was beaten and left for dead, that that's the bridge that she built, when she dared not to move, when the person who was the conductor on this bus told her to get up, and go to the back, and give this white gentleman a seat. She refused to do it.

Now we had been marching, and we had been demonstrating. We asked, we sent petitions, to be able to get civil rights and the Voting Rights Act. It did nothing. But when she refused to go to the back of that bus, then she began to build that bridge across the Alabama River, and of course, it flowed all over the United States. And Rosa knew that she would be arrested, but she decided, I'll take it, come what might be....

Then, they called all of the ministers together. And you know, God works in a mysterious way. Dr. King had been in Montgomery for a very short length of time, and when he went to this meeting, the fellow who called the meeting together said, "We are going to have a meeting, and we're going to organize." And there were the ministers who had been there for years, and somebody said, "Well, Mr. [E.D.] Nixon, I nominate you as the president of this organization," this new organization, which was the SCLC, Southern Christian Leadership Conference. And he [Nixon] said, "Gentlemen, I am an old man. I have stood between you and the evils of this city, and I decline in favor of this young man [Dr. King], who has just come to Montgomery, less than two years ago, and I nominate him."

And out of the blue skies—people didn't know anything except that he was a minister of this small church where the dignitaries were. And he accepted it. And his first suggestion was, "We are going to stay off this bus next week, beginning tomorrow, and during the week, we are going to stay off this bus."

Instead of one week staying off the bus, near Christmastime, it went on over a year, and put the buses out of business in Montgomery, Alabama.

He was a fearless man. And he went all over the world. And the legacy which he has left with us—I don't think it will ever die. If these young people know something about the legacy of Martin Luther King, then it will go on forever, and he will never die.

Bloody Sunday

That, of course, led to Bloody Sunday, and that's where the whole world got up in arms. Bloody Sunday was just an expression of the way of life of the people in the South: "We don't want our way of life disturbed. Don't do anything, don't have anybody coming in." Everybody was not racist, but everybody was fearful. The whites who didn't believe in what was going on, felt that they could not stand up and be counted, because, as one white woman said to me, "I would be suffering worse than you. Because I'd be ostracized." The blacks were saying, "I've got a job. I've got a house that I have to pay the mortgage on, so I can't afford to get out there."

So, it was just the young people—and I give all credit to the young people. Jim Clark was one of the worst sheriffs that Alabama, Mississippi, or any other place had. The city police were all nothing but racists, and they got them like that, because they wanted to keep their way of life, and their way of life was to beat up persons of color, going up to the courthouse and saying, "I did it because he made an attempt to hit me" or something. Written off as "justifiable homicide."

Innocent people were killed. Innocent people were jailed. Innocent people were, I say, crucified. They were run out of town, they had everything they had, taken away from them. I was arrested for walking down the street, and somebody said, "WWB"—walking while black. And I was just going down the street.

What happened, I was coming out of the courthouse, because the only way an African-American could vote was to have property, with no encumbrance whatsover. You must have money in the bank. You must not owe anybody. You must be able to recite the Constitution of the United States of America, and you must have two white men, not women—I think they figured that women had a heart—but two white men to vouch for you.

Well, I was taking the place of those two white men.

I was coming out of the courthouse, and I came down the street, and Jim Clark said to me, "Get in this line." I said, "I'm going to my office." He said, "Get in this line." I said, "I'm going to my office." He said, "I said, get in this line." He got behind me, grabbed me in the back, propelled me around—and there were 67 people, many of them elderly people, who were trying to get into the courthouse, to make an attempt to register. And when I passed them, they said, "Go on to jail, Mrs. Boynton. You won't be there by yourself. We'll be there with you."

Dr. King was across the street on the post office grounds. And of course, I went there, and these people came up. They were there about four hours. They charged them with unlawful assembly, but they were on the grounds of the courthouse, where they paid taxes. Now, I was kept there until about two o'clock, and I was charged with "criminal provocation." I don't know what that was, and it made no difference to me, because Dr. King and his group went to the house....

Now, mind you, when Dr. King came to Selma with his staff, nobody would offer him a drink of water. Nobody would say, "Come to my house." Nobody would come downstairs. They were on the same street with all of the dignitaries. Black on one side, City Hall on the other, and nobody offered him anything.

So, I gave him half of my office, and I turned my house over to them. And they went to the house, and tried to plan, what are we going to do? What program are we going to do, to let these people know that they're not going to stand for this? But they had not decided any specific thing to do.

Two nights after that, a fellow by the name of Jimmy Lee Jackson was killed. And when he was killed, they said, "We've got to do something." Jackson went to one of the meetings that we had—SCLC, a Southern Christian leadership meeting—and two state troopers, controlled by George Wallace, who was the governor, shot this young man in the back twice. And of course, he died. And one of the lieutenants of the SCLC, working with Dr. King, said, "What we need to do, is to take the body, and carry it to Montgomery, Alabama," which was 50 miles, "and put it on the Capitol steps."

But they thought that would not be sensible, because the body would be mortified by the time it got there.

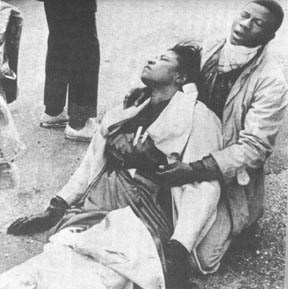

Amelia, on that Edmund Pettus Bridge was gassed, beaten and left for dead on ``Bloody Sunday,'' March, 1965.

So, they decided that we would march to Montgomery. On Sunday, March 7, 1965, we decided that that's what we were going to do. We left the church, and we had been marching, but we had not gone over the bridge (the Alabama River borders Selma, Alabama). We started marching. It happened that I started out the second from the front. Hosea Williams and John Lewis, who's a Congressman now, led this march. And I noticed, when we got across the river, there were state troopers. They had on gas masks, they had billy clubs, and they had—some of the people said it was a cattle prod. There were people on horses. There were people who had cannisters of gas.

And when we were told to stop, the front stopped. By that time, two or three people had come in front of me, and I think they knew what was going to happen. I had planned on walking a part of the way, not all of the way. But when they said stop, the line stopped. And one gentleman, Hosea Williams, said, "May I have something to say?" "No, you may not have anything to say. Charge on them, men!"

And they came from the right, they came from the left, a few of them came from the front, because we were near the sound truck. They began to beat people. They had horses, and tried to make the horses step on people, and the horses, every one of them, stepped over them. They shot this tear gas, so it was just as dark as before daybreak. And when that happened, people began to run, back across the river to the church, or to their homes. And these people were right behind them, with tear gas, right behind them with billy clubs, beating them; some of them fell.

I was rather amazed. I just stood there. And one guy came up to me, and said, "Run!" I looked around, and everybody had run. I saw one or two people still trying, in a crippled way, to get off of the road. And I just stood there. He said, "I said, run." I just looked at him, because I thought he was crazy, telling me to run. For what reason? Then, I was hit in the back, and I just accepted, and I figured by the time he got out of my way, I was going to walk on back across the bridge. And the second time he hit me, was at the base of my neck, and I fell to the ground, unconscious.

I didn't know what happened, except what the newspapers said, and all of the news media and whatnot. And I talked with some of the people. When I fell to the ground, I was beaten. For what reason, nobody knows. But when they got through, and they were tired, they walked off and left me. There was nobody on the road but me. Then, they didn't know whether I was alive or dead.

On the Selma side, Jim Clark was standing there, to see that everybody had done a good job. And one of the African-Americans went up to the sheriff, and said, "Sheriff, somebody is dead over there. Send an ambulance." And he said, "Send an ambulance? If there's anybody dead over there, let the buzzards eat 'em. I'm not sending any ambulance over there." So, it was reported to the funeral home, and they sent an ambulance, picked me up, carried me to the hospital, where I stayed a couple of days. And when I woke up, I said, "What happened?" I didn't know all of this had happened.

But, the news went out. Dr. King was supposed to have led that march, and I'm quite sure somebody knew what was going to happen. When Dr. King heard about it, he called people from all over the country, and foreign lands, to come to Selma, because he needed them. And they came. And it frightened the racists: "What's going on? How did they get these people together?" And they came.

But that night, when I was beaten—and that was not the supreme price for liberty and for justice. Because that night, three men who were with Dr. King, had come from Boston, and they went to an African-American restaurant. Coming out, they turned the wrong way, and there was a white restaurant, with three white racists. They came over where they were, and started beating them. One of the guys was beaten so badly—Jim Reeve from Boston—that they brought him to my office, and then finally, they said, "Take him to the hospital." And because he was white, they took him to the white hospital. But they refused to take him in. He was beaten so badly, that he was unconscious.

Then they took him to the African-American hospital, that didn't have the facilities, and they immediately took him to Birmingham, Alabama, 90 miles away, and in three days time, he died. That was a supreme price that was paid, for liberty, and for justice.

But, it paid off. I mean, somebody makes a sacrifice for the good, that is being done throughout the world, even to this day; somebody has made a sacrifice.

'Too Much for Me To Do'

When I got better, I felt as though I was more determined than ever. I was single then; I was a widow.

Then, in 1970, I married again.

[She describes going for a pleasure boat ride in Savannah, Georgia, with her husband, and the tragedy that ensued when the boat overturned, and everyone except herself and one other woman drowned.]

The water was 42°, and I'm saying to God every moment, "I can't afford to drown. I just can't afford to drown, God. I've got too much to do."

Well, what did I have to do? Nothing!

This is why I believe in faith. If you have faith as small as a mustard seed, you can accomplish something....

[She then describes meeting her third husband. The two of them went to a Shriners meeting in New York City, where she first encountered the LaRouche movement, the International Caucus of Labor Committees (ICLC).]

A young man came up, and he said, " 'Rah-rah-rah," and I didn't pay any attention to him. And I said to myself, "Here's my six-foot husband over me. What's he doing talking to me?" And finally he said, "And we have a blueprint that we can put water across the Sahara Desert." And the first thing I said was, "Ah, if Dr. King were living, he would be interested in this."

And then he spoke about getting drugs out of a certain community in New York City. He invited me to come back, and I invited him to come down to where I was staying. He said, "I'm with ICLC." I said, "Who has charge of it?" He said, "Lyndon LaRouche." And I said, "Oh, I never heard of him."

So I began to investigate. And naturally, whenever there's anybody that is doing something, don't think that people aren't throwing rocks at them. Some said, "I never heard that name before." Others said, "Well, they say...." I said, "What do you know?" "I don't know anything, I just heard." So that was what I got.

Dennis Speed and Amelia Boynton Robinson

Finally, I was invited to go to one of the conferences. And this guy [LaRouche] stood up, and he started talking, and my mind went back to the struggle that my husband [Bruce Boynton] and I had, trying to get people off the farm, where they never knew anything about an income. And I saw how all of the people in the South almost couldn't register and vote, and hearing him, and thinking about what Dr. King had been doing, I said, "This sounds like everything that we had done, everything that we stood for, everything that Dr. King stood for, all wrapped up in one." So I said, "This is the place for me."

And really, when I said to God that I couldn't afford to drown, because I got too much to do—be careful what you ask of Him, because you'll get it! You will really get it! If you believe, you trust, and you put forth effort, you're going to get it.

And I've been the happiest person in the world, because of having met the Schiller Institute, which was founded in 1984, and nobody can say anything, or get me off the course, because I feel dedicated to these young people. And what makes me feel so good, is when they come up to me, and say such things as, "I was on the wrong way. I was going the wrong way, and you said such-and-such a thing, or I read something that you said."

That's one thing that I feel very proud of, of these young people and what can be done....

[She discusses Hurricane Katrina, and the havoc that it wreaked among the people of New Orleans, while the Bush Administration did nothing.]

Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. and Amelia Boynton Robinson

There's something that needs to be done. And the only thing is unity, to get together with this organization, the Schiller Institute, and get in numbers. And we'll have to do like the missionaries: We go out, and get the hand of the young people who are doing an extra good job, and compel others to come in. Because, as long as the oligarchy can do as they choose, and can take what they want, and look at us as being ants, or somebody who's just a hewer of wood, or drawer of water, for their own benefit, we will always be a people that will not get what we should get, according to the system....

We need to go to the highways, and the byways, and compel the people to come. Because we realize, wherever there is unity, there is strength. So, we have to get together, and work with this organization, and do what we can to encourage these young people, that whatever your vocation is, then we're able to help them.

And so many times, people have said, "Since I joined this organization, I've straightened out. "

Help them to straighten out, please. Because they are our future. Unfortunately, what we're handing to them, I don't think we're pleased with it. But let us try to build them, where they're strong enough, that they will do something about the condition in which we are today.

And it's not only the United States of America. It's the whole world. Let us try to save the world. Because they need us, the world needs us. And it needs the young people. And let us do all we can, to make this world what we would like for it to be.

Thank you.

Related Links:

More Speeches from the Schiller Institute Conference

Amelia Boynton Robinson Book Excerpt

Spider Martin's Photo Gallery of the Selma to Montgomery, Alabama March

What is the Schiller Institute?

Birthday Celebration in Alabama, August 2007

Amelia Boynton Robinson Organizes the Swedish Nation and Youth

Amelia Boynton Robinson Tells Denmark: Listen to the Wise Words Of Lyndon LaRouche

Danish TV Coverage of Amelia Boynton Robinson

Birthday Greetings from Helga Zepp LaRouche

Amelia Robinson in Houston. (Video)

Amelia Robinson on Jim Clark Funeral

Amelia Robinson Honored in Italy

Amelia Boynton Robinson Honored in Alabama

Bloody Sunday March Reenactment

Through The Years- January, 1995

August 27, 1993 Celebration of Inalienable Rights of Man