Home | Search | About | Fidelio | Economy | Strategy | Justice | Conferences | Join

Highlights | Calendar | Music | Books | Concerts | Links | Education | Health

What's New | LaRouche | Spanish Pages | Poetry | Maps

Dialogue of Cultures

‘Four Serious Songs’—

An Introduction

by Anno Hellenbroich

For related articles, scroll down or click here.

This article appeared originally in Ibykus magazine, the German-language sister-publication of Fidelio, in issue Number 81, 2002.

|

|||

|

Johannes Brahms

|

|||

"... It was more an intensified recitation of Biblical text in tones, which he gave us in his hoarse voice; and what we heard was entirely different than an art song. Since then, no singer, not even Meschaert himself, has been able to awaken the same mighty impression in me, which the improvised rendition of these songs by their creator made on me at that time. It was actually no different than if the prophet himself had spoken to us." Ophüls mentioned Brahms' shaking while performing the third song: "The third song, 'O death, how bitter thou art,' plainly gripped him so strongly during its delivery, that during the quiet close, 'O death, acceptable is thy sentence,' great tears rolled down his cheeks, and he virtually breathed these last words of the text, with a voice nearly choked with tears. I shall just never forget the moving impression of this song."

The "Four Serious Songs" were the last songs composed by Brahms, then 63 years of age. He died less than a year later, on April 3, 1897. This song-cycle for bass voice and piano, which uses texts from the Old Testament, and the famous words of St. Paul to the Corinthians, "Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels and have not charity [love, agape], I am become as a sounding brass and a tinkling cymbal," culminating in the exclamation, "But now abide faith, hope, and charity, these three, but the greatest of these is charity," has the character of a musical last will and testament by Brahms. (Opus 122, his very last compositions, are eleven organ chorale preludes, which Brahms completed in 1896.)

Musical Testament

In this work of art, Brahms has musically posed the central questions of human existence. If man dies just as beasts do, what about man's spirit? What outlasts death? What is essential for the future, the generations yet to come, which distinguishes man from beasts? ("Who knoweth the spirit of man that goeth upward?... For who shall bring him to see what shall be after him?"—from Song 1). What about all the evil, all the injustice, which befalls man because of his own too great power? (Song 2). Death is bitter for men, who live without sorrows; can it "do well"? ["acceptable is thy sentence ... " in the King James Version]. Can it be a deliverance for him who can expect nothing better? (Song 3). "And though I bestow all my goods to the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing. But now abideth faith, hope, and charity, these three, but the greatest of these is charity" (Song 4). [see comparison of songs and Biblical text]

Brahms did not call his work "Four Spiritual" or "Four Biblical" songs, but rather "Serious" songs. So he makes it clear in the title, that these solo songs with piano would permit to resound in an almost symphonic dimension, questions which confront all men, questions of mortality and eternity, from which none can escape. Actually, in their artistic affirmation, they are a challenge to the imprisonment of human activity within sense perception, comparable to the great Bach Passions, or Beethoven's Ninth Symphony or Missa Solemnis.

Brahms composed them as a cycle, although composition of the fourth song, the "high song of love" of the New Testament, was completed somewhat earlier. Since his youth, Brahms had made a habit of writing out important text fragments from the classics, poems, and aphorisms. Thus, he had collected more than five hundred quotations, from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Lessing, Jean Paul Richter, Schiller, Goethe, but also from Schumann and Beethoven, and others. "I invested all my money in books; books are my highest desire; since infancy I read as much as I could, without any guidance in distringuishing the worst from the best. As a child I devoured countless chivalric romance novels, until The Robbers fell into my hands, which I had no idea had been written by a great poet. I demanded more from this same Schiller, after which I did get more," Brahms had said (from the account in the diary of Hedwig von Solomon, of his first meeting with the twenty-year-old Brahms). Likewise, Brahms gathered a notebook full of Bible quotations. The passages he selected for setting in his musical compositions closely correlate to these notebook entries. As the Apostle Paul wrote in I Corinthians 13, in the passages selected by Brahms as the text for the fourth song, "For now we see through a glass, darkly, but then face to face ... but the greatest of these is charity." This selection of verses overarches all the previous songs, showing, as it were, Brahms' intention to achieve a large, self-developing unity of the four songs.

In this way, Brahms was able to compose the continuity into each song, through a musical tracing out of the ordering principle of the paradoxical ideas, of these "unrhythmical" verses, engendering the effect of a "strophe."

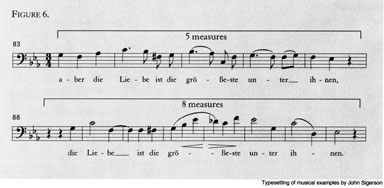

Thus, Brahms' musical approach is able to unfold the full effect, through the repetition—therefore through the transformation—of Biblical texts, or through the insertion of a refrain, so that the single song works more intensively "strophically," but also retains an "individual profile." This is especially clear in the third song: "O death, o death [repeated], how bitter, how bitter [repeated] thou art"; then between the second and third verses, this part is repeated as a refrain [see: Figure 1].

Brahms was able to carry forth the ideas through motivic variation, and in this way, to form a song and a cycle with almost invisible ligaments. In this way, the "second strophe" of the third song (O Death), "how well thou dost" (wie wohl tust du) is the inversion of the motif of the first strophe.

![]()

The displacement of accents, changes in timing and so forth, often produce a self-reflexive element in the development of the song, which unlocks the poetic effect, first in the development, and then in the broadening of the whole.

So, for example, in the first song: Denn es gehet dem Menschen wie den Vieh (on the stressed beat), wie dies (stressed) stirbt, so stirbt (stressed) er auch (stressed), etc. (Or, in the English-language equivalent, in the words of the King James Version: "that which befalleth the sons of men befalleth beasts, ... as the one dieth, so dieth the other [also].") [see: Figure 2]

Also, Brahms succeeds in creating an obvious deepening of the thought, by separating by three beats the two appearances of the word "stirbt" ("dies"), and letting the second appearance sink into the first register of the bass voice (G-natural).

The motif of the singer's part is something carried forward from the first two measures of the piano part. Brahms lets the dominant tone A (in D minor), like an anchor, play virtually throughout, as a bass ostinato. One is reminded of the choral entrance in Bach's St. John Passion, in which Bach—in the greater dimension of passion—prepares the musical tension for the mighty choral entrance "Herr unser Herrschen" ("Lord our Ruler") through the close, stepwise movement of the violins and violas over the ostinato bass.

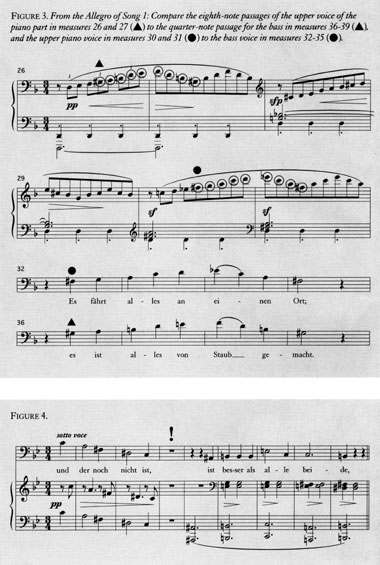

Brahms develops various polyphonic usages, such as augmentation and canonic dialogue—while preserving all the individuality of each song—in order to make audible the organic unity of the whole. [see: Figure 3]

Here it becomes clear, how Brahms deliberately seizes and develops aspects of the Bachian or Mozartian musical language, in order to motivically interlace the thought ''... es fährt alles an einen Ort ... es ist alles von Staub gemacht, und wird wieder Staub" ("all go to one place ... all are of the dust, and turn to dust again") with the closing thought "denn wer will ihn dahin bringen, daß er sehe, was nach ihm geschehen wird?" ("for who shall bring him [man] to see, what shall be after him?"). For augmentation of the theme and diminution of the note values were Bach's means to lawfully represent polyphonic thoughts via an increasingly closer spacing of different thematic entrances, as the musical work proceeds. (Bach's Musical Offering is examplary of this.) Brahms generates the musical intensity of the closing question of the First Song, "was nach ihm geschehen wird?" ("what shall be after him?") through the rhythmic change from the 3/4 meter of the reprise-like allegro part, to the 9/4 meter of the closing, proceeding along with the long note values, the equivalent of a long, sustained cry.

In his recollections of Brahms, Ophüls also recalls the following observation by Brahms: "You simply wouldn't believe, how difficult it is to compose this unrhythmical Bible text."

In teaching, as his student Gustav Jenner reports, Brahms advised the following for the process of composition:

"Brahms demanded of a composer, first of all, that he know the text exactly. By that, of course, he was also to understand that by all means, the structure and meter of the poem be clear. Then he recommended to me, that I carry the poem I intended to set, around in my head for a long time, and that before composing it, I recite it aloud more frequently, thereby to pay exact attention to what the recitation entails in particular, especially taking note of the pauses, to retain this later for the work."

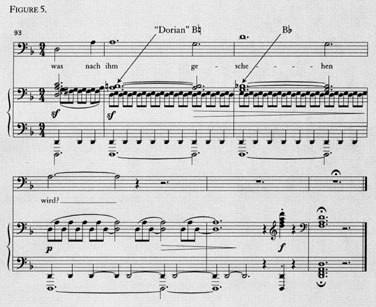

Song 2 contains a dramatic example of a setting of a "pause." Just after the words, "Da lobte ich die Toten, die schon gestorben waren, mehr als die Lebendigen, die noch das Leben hatten; und der noch nicht ist" ("Therefore I praised the dead which are already dead more than the living which are yet alive, ... and they which have not yet been"), Brahms places a complete measure of rest for both voice and piano, and only then, after this sustained stillness of the "not-yet-been" ("Noch-nicht-sein"), concludes the verse: "ist besser als alle beide und das Bösen nicht inne wird, das unter die Sonne geschieht" ("better is he than both they, which have not yet been, who have not seen the evil work that is done under the sun"). [see: Figure 4]

Throughout his life, Brahms intensively studied his musical forebears. For example, on Nov. 20, 1893, Brahms sent an astounding tabulation to Billroth, a friend of many years, following up a discussion about the predominance of major or minor in the pre-Bach period. Since Billroth asserted that the minor would predominate in all periods, just as in the oldest folk songs, Brahms drew up a list, which he called "statistical contributions pertaining to major and minor." He "classified," in this way, Bach's cantatas, 65 in major and 55 in minor, and in the same fashion the works of Beethoven, Haydn, and Mozart, as well as Clementi. Brahms laid out a similar "collection of interesting passages of the old masters," a technical study of passages from compositions of thirty-two composers, in which he gives an account of their uses of especially the intervals of the fifth and the octave.

In the "Four Serious Songs," Brahms composed with a method of modal transformations which broke through the earlier uses of modality that had arisen in earlier stages of musical development, beginning with the "church modes" around the Sixteenth century, then through the establishment of a clear polarity between major and minor, which Beethoven then went beyond, in his late works (around Op. 132), using modes in a new way, to produce new expressive possibilities. An example is the closing phrase of the first of the Serious Songs: "Denn wer will ihn [here a change from 3/4 to 9/4] dahin bringen, daß er sehe, was nach ihm geschehen wird, was nach ihm geschehen wird?" ("For who shall bring him to see what shall be after him?") One hears a gradual changing over (through a piano trill) into the Dorian mode (measure 94, B-natural), then to D minor, where the B-natural (which doesn't "belong") lets the thoughts of the last verse of the First Song ring out with an archaic effect, with the help of the trill between the D and A, an open fifth, the central tones of this song. [see: Figure 5]

Certainly in the entire musical literature of the Nineteenth century, there is no other comparable work for solo voice and piano using text from both the Old and New Testaments. Only Dvorák, the Czech composer much promoted by Brahms, published ten "Biblical Songs" (Op. 99) for low voice in 1894. In fact, Brahms' work towers as a testament for our times. Through his condensation of the language of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, in his collation of millenia-old verses, Brahms left behind a musical work, which the composers of the future, who intend to create something new and essential, must study in the most serious way.

Brahms: 'They Are Seriously Disturbing'

On May 7, 1896, Brahms' biographer, Max Kalbeck, and the writer Wilhelm Raabe, were present at the celebration of Brahms' sixty-third birthday. In the course of the conversation, Brahms said, "I gave this to myself as a gift today. Yes, to myself! If you read the text, you shall grasp why." He took a bundle with the "Four Serious Songs" out of his standing-desk and said, "I wouldn't think publication of these would be allowed." Yet, the day after his birthday, Brahms wrote a letter to Simrock, in which he announced the songs. He wanted to give his publisher "a little joy—as I did for myself today, in that I wrote a few little songs for myself. I'm thinking about publishing them — and about dedicating them to Max Klinger! So you see, that actually they're not just for fun—in fact, the opposite. They are seriously disturbing, and therefore so Godless that the police could prohibit them—if they weren't all taken from the Bible."

In his recollections of the 1896 Feast of Pentacost, Gustav Ophüls cites similar statements by Brahms, after Brahms had performed the songs a second time for this small circle, repeating the first three. He addressed the question to Ophüls, who was the assistant judge of Dusselforf, "whether in some way the public circulation of these songs, already sitting at Simrock's ready for publication, could be prohibited on religious grounds. Today [1920—A.H.], I no longer recall exactly what I said in reply, but I do remember that I strongly expressed the conviction that such an extreme juridical measure would be a disgrace and a dishonor to art. Today, twenty-three years later, when the 'Four Serious Songs,' this monumental capstone of Brahms' life's work, have become the common possession of the whole world, the doubt lurking in Brahms' question seems scarcely comprehensible to us."

In letters and conversations, Brahms generally did not refer to his work as "little songs," but rather as "Alpine folk songs" or as "merry songs"—obviously an idiosyncratic and ironic characterization, with the intent of counterposing the paradox in these songs to the reigning pessimism of the day—the pessimism of a Schopenhauer, or Nietzsche, or likewise of Wagner.

|

|||

| Clara Schumann in her later years. Shortly after her death, Brahms wrote to her daughter: “you won’t be able to play through these songs,, while the words are still gripping you. But I implore you to regard them, really, as your own sacrifice for the death and memory of your beloved mother” |

|||

For Performance, ‘As Beautiful in the

Hearing as in the Imagining’

After receiving a copy of the "Four Serious Songs," violinist Joseph Joachim, Brahms' friend of many years, sent Brahms a letter of thanks, in which he wrote, "I thank you from my heart for your 'serious' songs. Profound as they all are, I was especially moved by the last, with its tender ardour, built from all the artistic periods, which anyone who studies it correctly would notice at once. How beautifully love shines through in the 3/4 section, and how the reentry of the 4/4 touches the heart! Were it possible, that just once, it could be as beautiful in the hearing as in the imagining" (Aug. 28, 1896, to Brahms).

"Were it possible, that just once, it could be as beautifuul in the hearing as in the imagining." One wishes that this sentence would be taken to heart by more artists, in the interpretation of Classical works. For a work of the greatness of the "Four Serious Songs" is wrecked, in performance, if the singer and pianist present the piece according to the prevailing trend of "sensuous effects." Any straining for sensuous effect, or any attempt to perform them while avoiding the emotion of love, agape, the question of the transcience and immortality of man, which the artist resolved, as his own existential question, will wreck the profound ideas of the work.

Besides other important historical and contemporary recordings of the "Four Serious Songs," sung by bass, baritone, or alto voices, there is an early recording of Dietrich Fischer-Diskau which is especially rewarding for study, for this recording was made following an intensive, if brief, period of collaboration between Fischer-Diskau, then at the beginning of his career, and the great conductor and musician Wilhelm Furtwängler. Furtwängler always strove to bring forth that which sounds "between the notes," in long musical phrases.

Mrs. Elisabeth Furtwängler recently gave an account, in an interview with Fidelio's sister-publication Ibykus, of the meeting between Furtwängler and the young Fischer-Diskau: "It was in the context of the Salzburg Festival, I believe in 1949. The 'cellist Mainardi, a great friend of ours, told Wilhelm that, without fail, he should listen to a certain young singer: 'It is definitely worth your while; his wife is in my 'cello course.' To which Wilhelm replied, 'If you see him, please tell him he should come by to see me.' That meant of course, that it was arranged for that evening; it was at a Countess's in Salzburg. Now, there were only a few in the audience, eight including myself, in addition to the hostess, and naturally Fischer-Diskau and Wilhelm.

"Right at the beginning, my husband asked Fischer-Diskau, in a rather skeptical tone, 'What have you brought along?' 'Brahms' "Four Serious Songs." ' 'Ahhh! Well! Yes! So that's what we'll do.' They began at once, and as was immediately clear, it was exquisite! They suited one another very well, and I thought Wilhelm was the more fortunate.

"At the conclusion, everyone naturally wanted to hear what Furtwängler would say now about the young singer. But Wilhelm wanted to talk to him completely personally, so he took Fischer-Diskau with him behind one of the heavy curtains, which this castle had, and spoke quietly with him. That's how immediately positive he was about him, that he wanted just to communicate alone and completely personally."

This was the beginning of Fischer-Diskau's great singing career. He and Furtwängler worked together in increasingly frequent joint performances, such as the legendary St. Matthew Passion performance of 1954—also the year of Furtwängler's death—in which Fischer-Diskau sang the role of Christ.

The 1950's recording of the "Four Serious Songs" is especially remarkable for the effort made to adequately bring to a recording, the great tension spanning the soloist's opening words, "O death, how bitter art thou," with the distant, soaring concept closing the four songs, "Now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity."

—translated from the German by Alan Ogden

———————————————————————————-

King James Bible and Brahms’ Text Compared

Bible Text |

Brahms’ Text |

||||||||

|

Song 1. |

1. Gesang |

||||||||

|

Song 2. |

2. Gesang Andante Ich wandte mich, und sahe an alle, die Unrecht leiden unter der Sonne, die Unrecht leiden unter der Sonne; und siehe, siehe, da waren Tränen. Tränen derer, die Unrecht litten, und hatten keinen Tröster und die ihnen Unrecht täten, waren zu Mächtig, daß sie keinen Tröster, keinen Tröster haben konnten. Da lobte ich die Toten, die schon gestorben waren, mehr, denn* die Lebendigen, die noch das Leben hatten; Under der noch nicht ist, ist besser als alle beide, und des Bösen nicht inne wird, das unter der Sonne geschieht. |

||||||

|

Song 3. |

3. Gesang |

|||||

|

Song 4. |

4. Gesang Wir sehen jetzt durch einen Spiegel in einem dunklen Worte, dann aber von Angesicht zu Angesicht. Jetzt erkenne ichs stückweise, dann aber werd ichs erkennen, gleichwie ich erkennet bin. Nun aber bleibet Glaube, Hoffnung, Liebe, dise drei, aber die Liebe ist die Größeste unter ihnen, die Liebe ist die ist die Größeste unter ihnen. |

|||||

The Question of Motivic Thorough-Composition in Schiller's Poetry by Helga Zepp-LaRouche

Brahms and the Paradox of Mortality, by Fred Haight, assisted by the Schiller Institute Chorus;

ENGLISH Audio /Video Archive SPANISH Escuchar el Audio

Listing of online music related articles

Essay on Brahms by Conductor Wilhelm Furtwaengler, 1934

Excerpts from “Johannes Brahms as Man, Teacher and Artist,” by Gustav Jenner , 1930

Fidelio Table of Contents from 1992-1996

Fidelio Table of Contents from 1997-2001

Fidelio Table of Contents from 2002-present

Beautiful Front Covers of Fidelio Magazine

Join the Schiller Institute,

and help make a new, golden Renaissance!

MOST BACK ISSUES ARE STILL AVAILABLE! One hundred pages in each issue, of groundbreaking original research on philosophy, history, music, classical culture, news, translations, and reviews. Individual copies, while they last, are $5.00 each plus shipping

Subscribe to Fidelio:

Only $20 for 4 issues, $40 for 8 issues.

Overseas subscriptions: $40 for 4 issues.

PO BOX 20244

Washington, DC 20041-0244

703-297-8368

schiller@schillerinstitute.org

Home | Search | About | Fidelio | Economy | Strategy | Justice | Conferences | Join

Highlights | Calendar | Music | Books | Concerts | Links | Education | Health

What's New | LaRouche | Spanish Pages | Poetry | Maps |

Dialogue of Cultures

© Copyright Schiller Institute, Inc. 2001- 2003 All Rights Reserved.